Jamie Reid had a premonition of punk years before it hit. His 1972 painting Monster on a Nice Roof portrays a giant green beast perched on the roof of a suburban home as broiling storm clouds gather above: it seems in retrospect to foretell the monster that was punk.

What exactly happened to Britain in 1977 – when Reid’s cover for the Sex Pistols’ single God Save the Queen covered Elizabeth II’s eyes with the title in cut out lettering and her mouth with the band’s name – has been amply picked over by cultural theorists and pop historians. It has been seen as anything from a raw blast of working-class honesty (the interpretation favoured by John Lydon) to an apocalyptic consummation of the most radical ideas of the 20th-century avant garde.

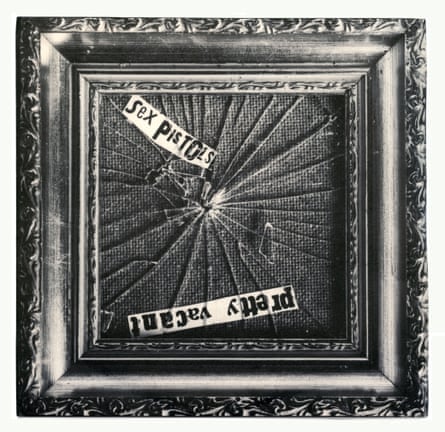

Whatever it was, it was real, for a moment, and created a truly wild atmosphere of violence and revolt. My dad, who was vice principal of a Welsh sixth form college, told me he warned a lad that if he didn’t take the safety pin out of his ear he’d pull it out. I knew I’d never be able to smuggle the Sex Pistols album into the house, largely because Reid plastered Never Mind the Bollocks Here’s the Sex Pistols in luridly screaming pink and black on its bright yellow sleeve, which in those vinyl days was a surface 31.4cm sq. Unhideable.

Looking back, my entire adolescent record collection may have been an effort to purchase Never Mind the Bollocks by other means, which, by Freud’s theory of repression breeding perversion, led to the far more decadent delights of the Velvet Underground.

So the first and crucial thing to be said about Reid’s art is that he knew how to be crude. He responded to the raucous riot of the Pistols’ music with designs like a V sign, the cover art equivalent of “come and get me, copper!”, which the coppers promptly did when they raided a record shop in Nottingham for displaying the cover.

Reid retained that capacity for calculated crudeness. His poster Free Pussy Riot, created to support the Russian feminist punks after the 2012 conviction of three of them for “sacrilegious hooliganism”, portrays Vladimir Putin in a black balaclava wearing lipstick: in Reid’s never mind the bollocks lettering it declares: “Putin says he’s seen the light / And he sold his soul for punk.” Reid’s gender bending onslaught on Putin and his fascist regime has even more urgency now – and it shows how seriously he took punk, believing it a genuine revolutionary force, whether aimed at a sclerotic British establishment or Putin’s bigoted diktat.

Sex Pistols themselves have labelled God Save the Queen as “camp” yet Reid’s travesty of her face has deadly intent, like his unmanning of the consciously manly Putin. He actually did want to live in anarchy. And he learned his anarchy from art, or rather anti-art.

Reports on his death have trotted out comparisons of his lettering with a “ransom note”, as if he was one of the Great Train Robbers. But its actual origins can be found in dadaism, the art movement created by a handful of German youths evading the first world war draft in Switzerland. They called it “dada” because it was babyish, primitive, incoherent, an attack on art itself, on the fake civilised ideals of the Europe that was mincing its young in trench warfare. In Berlin in 1919, dada crossbred with Marxist revolution in cut-up images and texts including those of the great collagist Hannah Höch. She not only chopped up and mutated images of politicians, just as Reid would rearrange the Queen’s face, but pasted in words hacked out of newspapers. This criminal looking dada aggression was also pioneered by her comrades George Grosz, Raoul Hausmann and John Heartfield.

If Reid made his aesthetic seem innocently raw and spontaneous, a threat from the gutter, this was a brilliant obscuring. For it resurrects the manic anti-art that was dada. Amazingly, those British authority figures goaded to swear back at the Pistols, raid record shops or threaten to pull safety pins from kids’ ears were reacting to a restatement, at least in Reid’s art, of the original subversive dada cabaret.

Can art change the world? Reid made you believe it can.