It's Saturday morning, April 26 2003, and I am mountain biking by myself on a dirt road in Emery County, Utah. I am on day four of a five-day excursion of hiking and biking through this arid but extraordinarily beautiful wilderness of geological wonders. An hour ago, I left my truck at the trailhead and set off into the Canyonlands National Park.

A mile past Burr Pass, my tortuous ride into a stiff headwind finally comes to an end. I dismount and walk my bike over to a juniper tree and fasten a U-lock through the rear tire. I have little worry that anyone will tamper with my ride out here, but as my dad says, "There's no sense in tempting honest people." I drop the U-lock's keys into my pocket and turn toward the main attraction, Blue John Canyon. After I've hiked through some dunes of pulverised red sandstone, I come to a sandy gully and see that I've found my way to the nascent canyon. "Good, I'm on the right route," I think.

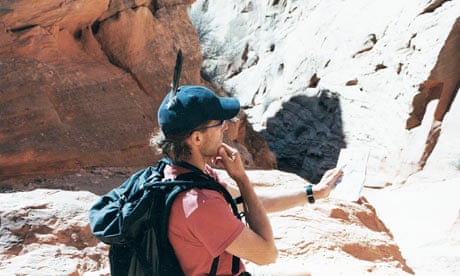

Soon, 300ft walls are fencing me in five feet to either side. Down here you can't really lose the route as you can on a mountainside, but I've got disoriented before. I am about half a mile away from the narrow slot above the 65ft-high Big Drop rappel. This 200-yd-long slot marks the midpoint of my descent in Blue John and Horseshoe canyons. Once I reach the narrow slot, there will be some short sections of downclimbing, manoeuvring over and under a series of chockstones, then 125 yards of very tight slot, some of it only 18in wide, to get to the platform where two bolt-and-hanger sets provide an anchor for the rappel.

Just below the ledge where I'm standing is a chockstone the size of a large bus tyre, stuck fast in the channel between the walls, a few feet out from the lip. If I can step on to it, then I'll have an easy nine feet to descend. I'll dangle off the chockstone, then take a short fall on to the rounded rocks piled on the canyon floor. Supporting myself by planting a foot and a hand on either side of the narrow canyon - a manoeuvre called "chimneying" - I traverse out to the chockstone.

With my right foot, I kick at the boulder to test how stuck it is. It's jammed tightly enough to hold my weight. I lower myself from the chimneying position and step on to the chockstone. It supports me but teeters slightly. I squat and grip the rear of the lodged boulder, turning to face back up-canyon. Sliding my belly over the front edge, I can lower myself and hang from my fully extended arms, akin to climbing down from the roof of a house.

As I dangle, I feel the stone respond to my adjusting grip with a scraping quake as my body's weight applies enough torque to disturb it from its position. Instantly, I know this is trouble, and instinctively I let go of the rotating boulder to land on the round rocks below.

When I look up, the backlit chockstone falling toward my head fills the sky. Fear shoots my hands over my head. I can't move backward or I'll fall over a small ledge. My only hope is to push off the falling rock and get my head out of its way.

Time dilates, as if I'm dreaming, and my reactions decelerate. Seemingly in slow motion, the rock smashes my left hand against the south wall; my eyes register the collision, and I yank my left arm back as the rock ricochets; the boulder then crushes my right hand and ensnares my right arm at the wrist, palm facing in, thumb up, fingers extended; the rock slides another foot down the wall with my arm in tow, tearing the skin off the lateral side of my forearm.

Then silence.

My disbelief paralyses me temporarily as I stare at the sight of my arm vanishing into an implausibly small gap between the fallen boulder and the canyon wall. Within moments, pain wells up through the initial shock. Good Christ, my hand. The flaring agony throws me into a panic. I grimace and growl a sharp "Fuck!" My mind commands my body, "Get your hand out of there!" I yank my arm three times in a naive attempt to pull it out. But I'm stuck.

Pain shoots from my wrist up my arm. Frantic, I cry out, "Oh shit, oh shit, oh shit!" My desperate brain conjures up the no doubt apocryphal story in which an adrenalin-stoked mom lifts an overturned car to free her baby. I'm sure it's made up, but I do know for certain that right now, while my body's chemicals are raging at full flood, is the best chance I'll have to free myself with brute force. I shove against the large boulder, heaving against it, pushing with my left hand, lifting with my knees pressed under the rock. I get good leverage and brace my thighs under the boulder and thrust upward repeatedly, grunting, "Come on ... move!"

Nothing.

I rest, and then I surge again against the rock. Again, nothing. I replant my feet. Feeling around for a better grip on the bottom of the chockstone, I reposition my upturned left hand on a handle of rock, take a deep breath, and slam into the boulder, harder than any of my previous attempts.

The stone's movement is imperceptible; all I get is a spike in the already extravagant pain. "Ow! Fuck!" I gasp.

I've shifted the boulder a fraction of an inch, and it has settled on to my wrist a bit more. This thing weighs a lot more than I do - it's a testament to how hyped I am that I moved it at all - and now all I want is to move it back. I get into position again, pulling with my left hand on top of the stone, and budge the rock back ever so slightly, reversing what I just did. The pain eases a little.

I'm sweating hard. I need a drink, but when I suck on my hydration-system hose, I find my water reservoir is empty. I have a litre of water in a bottle in my backpack, but it takes me a few seconds to realise I won't be able to sling my pack off my right arm. I remove my camera from my neck and put it on the boulder. Once I have my left arm free of the pack strap, I expand the right strap, tuck my head inside the loop, and pull the strap over my left shoulder. The weight of the rappelling equipment, video camera and water bottle tugs the pack down to my feet, and then I step out of the strap loop. Extracting the water bottle from the bottom of my pack, I unscrew the top and gulp three large mouthfuls of water and halt to pant for breath.

Then it hits me: in five seconds, I've guzzled a third of my entire remaining water supply.

I stop and take stock. Looking up to my right, a foot above the top of the boulder on the north wall, I see tiny wads of my flesh, pieces of my arm hair, and stains of my blood streaked on the sandstone. Gravity and friction have wedged the chockstone against the walls about four feet above the canyon floor. My hand isn't just stuck in there, it's actually holding the boulder off the wall at that point. Oh, man, I'm fucked, I think.

I take an inventory of what I have with me, emptying my pack with my left hand, item by item. In my plastic grocery bag, I have two small bean burritos, about 500 calories in total. In the outside mesh pouch, I have my CD player, CDs, extra AA batteries and mini digital video camcorder. My multi-tool and LED bike headlamp are also in the pouch. I pull out the knife tool and the headlamp, setting them on top of the boulder next to my sunglasses.

The major preclusion to rescue, I quickly calculate, is that I don't have enough water to wait long enough. I have 22oz left - little more than a pint - after my chug a few minutes earlier. The hiker's minimum for desert travel is a gallon per person per day. The average survival time in the desert without water is between two and three days.

It is Saturday afternoon now. On my scant supply I might last until Monday, maybe Tuesday morning at the outside. If a rescue comes along before then, it will be an unlikely chance encounter with a fellow canyoneer, not an organised effort of trained personnel. In other words, rescue seems about as probable as winning the lottery.

I have a problem to solve: I have to get out of here, so I put my mind to what I can do to escape my entrapment. Eliminating a couple of ideas that are too dumb (such as cracking open my extra AA batteries on the boulder and hoping the acid erodes the chockstone but doesn't eat into my arm), I organise my other options in order of preference: I can excavate the rock around my hand with my multi-tool; I can rig ropes and an anchor above me to lift the boulder off my hand; or I can amputate my arm.

A moment's thought makes each method seem impossible. I don't have the heavy tools to remove enough rock to free my hand. I don't have the hauling power needed, even with a pulley system, to move the boulder. And I don't have the instruments, surgical know-how, or emotional gumption to sever my own arm.

Perhaps more as a tactic to delay thinking about the last option, I decide to work on an easier option - chipping away the rock to free my arm. Picking an easily accessed spot on the boulder in front of my chest and a few inches from my right wrist, I scratch the tip of the multi-tool's longest blade across the boulder in a four-inch line. If I can remove the stone below this line and back toward my fingers about six inches, I will be able to free my hand. But I compute I'll have to remove about 70 cubic inches of the boulder. It's a lot of rock, and I know the sandstone is going to make the chipping tedious work.

My first attempt to saw down into the boulder barely scuffs the rock. I try again, pressing harder this time. Still scarcely a mark. Changing my grip on the tool, I hold it like Norman Bates and stab at the rock in the same spot. There is no noticeable effect. I try to identify a fracture line, a weakness in the boulder, something I can exploit, but there is nothing.

There is a phrase I know from a classic mountaineering guide: "Geologic Time Includes Now." It's an elegant way of saying, "Watch out for falling rocks." This chockstone pinning my wrist was lodged in its original position for a long time before I came along. And then it not only fell on me, it also trapped my arm. I'm baffled. It was like the boulder had been put there, set like a hunter's trap, waiting for me. This was supposed to be an easy trip, with few risks and well within my abilities. I'm not out trying to climb a high peak in the middle of winter, I'm just taking a vacation. What kind of luck do I have that this boulder, wedged here for untold ages, freed itself at the precise second that my hands were in the way? It seems astronomically unlikely that this happened.

I unfold the metal file from the tool and use it to etch the boulder. It works only marginally better than the knife when I saw down at the line. The rock is clearly more durable than the shallow rasps of the file. When I stop to clean the file, I see the grooves are filled with flecks of metal from the tool itself. I'm wearing down the edge without any effect on the chockstone.

I feel like I'm in the most deadly prison imaginable. My confinement will be an assuredly short one with only 22oz of water. Escape is the only way to survive. But all I have is this chintzy pocketknife to cut through this boulder. It's akin to digging a coalmine with a kid's sand shovel.

I become suddenly frustrated with the tediousness of pecking at the rock. Analysing how much rock I've chipped away (almost none) and how much time it's taken me to do it (over two hours), I come to the simple conclusion that I am engaged in a futile task.

My other options. I haven't yet tried to rig an anchor for a pulley system using my climbing rope, but I'm not optimistic: the rocks forming the ledge are six feet above my head and almost 10 feet away in total; even with two hands, that would be a difficult, perhaps impossible, task.

Without enough water to wait for rescue, without a pick to crack the boulder, without an anchor, I have only one possible course of action.

I speak slowly out loud. "You're gonna have to cut your arm off."

· This edited extract is the first instalment in a three-part serialisation of Between a Rock and a Hard Place, by Aron Ralston, published by Simon & Schuster.