Spending the day with a bunch of balaclava-wearing anarchists famous for being a thorn in Putin’s side and prone to crashing the World Cup final may not be many 71 year olds’ idea of fun. But then, they aren’t Jamie Reid.

“They were an absolute delight,” says the artist, recalling an afternoon spent with Pussy Riot after their performance at Liverpool’s Arts Club in August. “It really brought home to me what political art can achieve.”

If anyone knows about the combustible energy linking art and radicalism, it’s Reid. Over 50 years on the cultural frontline, he’s waged a visual war on social and cultural injustices, from Section 28 to the Criminal Justice Bill that effectively put an end to the rave scene. However, Reid is still best known for putting a safety pin through the Queen’s nose as graphic designer for the Sex Pistols.

“I’ve talked about that so many times,” he says, nursing a cup of tea in the cafe of the Humber Street Gallery in Hull. “I’d rather discuss what I’m doing now.”

This afternoon, Reid was marching through the Peak District with the director Julien Temple, shooting footage at Doll Tor, a stone circle dating from the bronze age, to mark the autumn equinox. It’s all part of a film they’re making together about his life, based on the Druidic eightfold year, the lunar and solar events celebrated annually. “It’s so important that we reconnect with the planet,” he says. “We need spiritual as much as political change in this country.”

Reid might talk like a table-thumping revolutionary, but he has the crumpled look of an eccentric country squire. Grey fronds of hair emerge from beneath a furry trapper’s hat, while his burly 6ft 2in frame comes wrapped in a Barbour coat. A life-long Fulham fan (“Don’t get me started, I’ll bore you to death”), he is thoughtful and softly spoken, his dark eyes twinkling with mischief.

“I’ve got a friend who knows some of the top computer hackers,” he says conspiratorially, as talk moves to society’s digital addictions. “They found out that the microchip is an alien technology, implanted to get the world totally dependent. It sounds mad, but it certainly makes you think.”

The same could be said of his latest exhibition, XXXXX: 50 Years of Subversion and the Spirit. Spread over three floors of the Humber Street Gallery, it’s a multimedia affair combining archive prints with rave-style projections and paintings inspired by aboriginal and Navajo art. A teepee lit by a glitter ball acts as a tribute to peace camps and indigenous cultures worldwide.

Perhaps the most surprising thing about it is that it’s Reid’s first ever retrospective in a recognised gallery. “There’s such an incestuous art world in this country,” he shrugs. “All the critics, artists and gallery owners are part of a network. You have to play a social game with them, and I’ve never done that.”

Reid has spent a lifetime kicking against the pricks. Born in Surrey in 1947, his parents were both “diehard socialists” who instilled in him a belief in social equality and a love of nature.

Having enrolled at Croydon Art School in 1968, he encountered a fellow student with a crazy mop of ginger hair called Malcolm McLaren. Sharing a passion for Guy Debord’s situationist manifesto Society of the Spectacle, the pair became fast friends, taking part in a student occupation which made the national papers.

Within two years Reid had founded his own radical magazine, Suburban Press, using cut-ups from newspapers purely because he couldn’t afford Letraset type transfer sheets. Having committed fully to the alternative lifestyle, he was learning the ancient art of crofting in the Outer Hebrides when he received a telegram from McLaren telling him about a group he was managing called the Sex Pistols.

With McLaren pulling the strings, Reid became punk’s provocateur-in-chief, wrapping the band’s sonic hand grenades in ransom note-style sleeves which sent shivers through the establishment.

“When God Save the Queen got to No 1 it proved there was genuine opposition to what was going on,” he says. “The trouble is that the people in control have made sure it will never happen again. Look at that last royal wedding. The media coverage was fucking unbelievable. There’s still dissent, you just don’t hear about it.”

When punk nihilism gave way to 80s hedonism, Reid’s confrontational graphics suddenly seemed old hat. By the middle of that decade, he was “desperate for money” and living in a squat in Brixton. It wasn’t until the 90s Britpop boom that Reid found his stock was back on the rise, with his work cited as an influence by a new generation of artists.

“I find it ironic that people like Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin talk about punk being a major influence,” he says witheringly. “To me they’re Thatcher’s children, because they were put into power by Saatchi & Saatchi.” Charles Saatchi and his brother Maurice’s advertising agency were in charge of the Conservative party’s election advertising; Charles was Britart’s first major collector. “There’s nothing remotely shocking about what they do.”

Talking of art’s capacity for outrage, what did he make of Banksy’s self-destructive stunt at Sotheby’s the other week? “I thought it was another cheap trick,” he sighs. “If Banksy was to donate all his money to the homeless, I’d respect him.”

In recent years, Reid’s restless muse has seen him work with everyone from Afro Celt Sound System to the KLF’s Jimmy Cauty. His belief in social justice, however, drives everything he does. Disheartened by Brexit (“a nightmare”) and cautiously supportive of Jeremy Corbyn (“I wish him all the best, but politics is a bear pit”) his simmering hatred of the mainstream only really boils over on the subject of celebrity culture.

“It’s an absolute obscenity. It’s how Trump and Boris Johnson have got to power, through The Apprentice and Have I Got News for You”.

Nonetheless, he’s wary of being drawn into a full-blown political discussion. “There are much darker forces behind what we see,” he says cryptically. “But I don’t want to get too David Icke about it.”

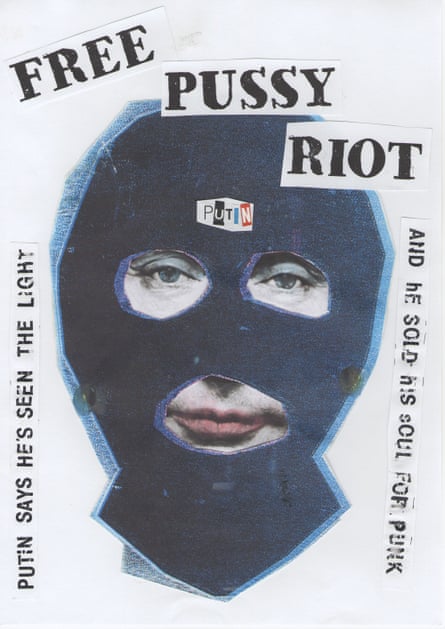

These days, Reid keeps his activism close to home. He moved to Liverpool in the 80s – he has a teenage daughter with the actor Margi Clarke – and raves about the city’s rebellious civic spirit. Each day, he works on his archive in a community building called the Florence Institute, which is where he met Pussy Riot. His association with them started when they were imprisoned in 2012: in response he made an image of President Putin wearing a balaclava.

The world keeps turning. The struggle goes on. The important thing, Reid stresses, is never to stand still.

“Radical ideas will always get appropriated,” he says in conclusion. “The establishment will rob everything they can, because they lack the ability to be creative. That’s why you always have to keep moving.”

At which point, he says his farewells, and does exactly that.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion