Trapped

Deep inside a remote canyon, a boulder shifts. In an instant, Aron Ralston's hand is pinned beneath half a ton of rock. So begins an ordinary hero's six-day ordeal of grit, pain, and courage—culminating in a decision to do the unthinkable.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

“It's 3:05 on Sunday. This marks my 24-hour mark of being stuck in Blue John Canyon. My name is Aron Ralston. My parents are Donna and Larry Ralston, of Englewood, Colorado. Whoever finds this, please make an attempt to get this to them. Be sure of it. I would appreciate it.”

It's April 27, 2003, and for the first time since my arm was pinned against the wall of this Utah canyon, I am using my digital camcorder to videotape myself. I take long blinks and rarely look at the camera's screen. What makes me avert my glance is the haggard expression in my eyes. They are wide-open, huge bowls; loose rolls of flesh sag and tug at my lower eyelids.

Picking up the camera, I point it first at my forearm and wrist, where it disappears in the horrifyingly skinny gap between a large boulder and the canyon wall. Then I pan the camcorder up over the pinch point to my grayish-blue hand.

“What you're looking at there is my arm, going into the rock … and there it is stuck. It's been without circulation for 24 hours. It's pretty well gone.”

Shaking my head in defeat, I yawn, battling fatigue.

I outline my failed attempts at self-rescue, and continue. “The other thing that could happen is someone comes. This being a continuation of a canyon that's not all that popular, and the continuation being less so, I think that's very unlikely before I retire from dehydration and hypothermia. Judging by my degradation in the last 24 hours, I'll be surprised if I make it to Tuesday.”

I know with a sense of finality that I'm saying goodbye to my family my parents and my 22-year-old sister, Sonja and that regardless of how much I suffer in this spot, they will feel more agony than me.

“I'm sorry.”

With tears brimming, I stop filming and rub the backs of my knuckles across my eyes. I start up once more.

“You guys make me proud. I go out looking for adventure and risk, so I can feel alive. But I go out by myself, and I don't tell someone where I'm going that's just dumb. If someone knew, if I'd been with someone else, there would probably already be help on the way. Dumb, dumb, dumb.”

Day One: Saturday, April 26, 9 A.M.

This is hoodoo country, Abbey country, the red wasteland.

Under a bluebird sky, I leave my truck at the dirt trailhead for Horseshoe Canyon, the isolated window of Canyonlands National Park that sits 15 air miles northwest of the legendary Maze District. My plan is to make a 30-mile circuit of biking and canyoneering through Blue John and Horseshoe canyons.

This vacation, a five-day road trip, was last-minute. Some friends and I had called off a mountaineering trip, and the cancellation freed me for a hajj to the desert from Aspen, Colorado, where I had a few days off from my sales job at the Ute Mountaineer, an outdoor-gear shop. Usually I would leave a detailed schedule with my roommates, but since I left without knowing what I was going to do, the only word I gave was “Utah.”

Though the Blue John circuit will be only a day trip, I'm carrying a 25-pound pack, most of the weight taken up with climbing gear for navigating the steep canyon system, food, and a gallon of water divided between a three-liter CamelBak hydration bladder and a one-liter Nalgene bottle. I'm wearing a pair of beat-up running shoes and wool socks, with just a T-shirt and shorts over my bike shorts.

Pumping against a 30-mile-per-hour headwind on a scraped dirt road, I finally make it to the entrance of Blue John Canyon and lock up my bike. By 2:30, I'm about seven miles into the canyon, at the midpoint of my descent, the narrow slot above the 65-foot-high rappel marked as Big Drop in my guidebook. Now the canyon deepens dramatically over a series of lips and benches.

I reach the first drop-off in the floor of the canyon, a ten-foot dryfall, and use a few good in-cut handholds on the canyon's left wall to lower myself. It's not a difficult maneuver, but I wouldn't be able to climb back up the drop-off from below. I'm committed to my course; there's no going back.

The pale sky is still visible above this ten-foot-wide gash in the earth's surface as I continue scrambling down, over lips and ledges and under chockstones boulders suspended between the canyon walls. The canyon narrows to just four feet wide here, undulating and twisting and deepening. It's 2:41 p.m.

I come to another drop-off. This one is maybe 11 or 12 feet high. A refrigerator-size chockstone is wedged between the walls ten feet downstream from the ledge, giving the space ahead the claustrophobic feel of a short tunnel.

Right in front of me, just below the ledge, is a second chockstone the size of a large bus tire, stuck fast in the three-foot channel between the walls. If I can step onto it, I can dangle off the chockstone, then take a short fall to the canyon floor. Stemming across the canyon with one foot and one hand on each wall, I traverse out above the chockstone. With a few precautionary jabs, I kick down at the boulder. It's jammed tightly enough that it will hold my weight. I lower myself from the chimneying position and step onto the chockstone. It supports me but teeters slightly. Facing upcanyon, I squat on my haunches and grip the rear of the lodged boulder. Sliding my belly over the front edge, I hang from my fully extended arms.

I feel the stone respond to my adjusting grip with a scraping quake. Instantly, I know this is trouble, and instinctively I let go of the rotating boulder to land on the round rocks on the canyon floor. I look up, and the backlit chockstone consumes the sky. Fear shoots my hands over my head. I can't move backwards or I'll fall over a small ledge.

The next three seconds play out in slow motion. The falling rock smashes my left hand against the south wall; I yank my left arm back as the rock ricochets in the confined space; the boulder then crushes my right hand, thumb up, fingers extended; the rock slides another foot down the wall with my arm in tow, tearing the skin off the lateral side of my forearm. Then, silence.

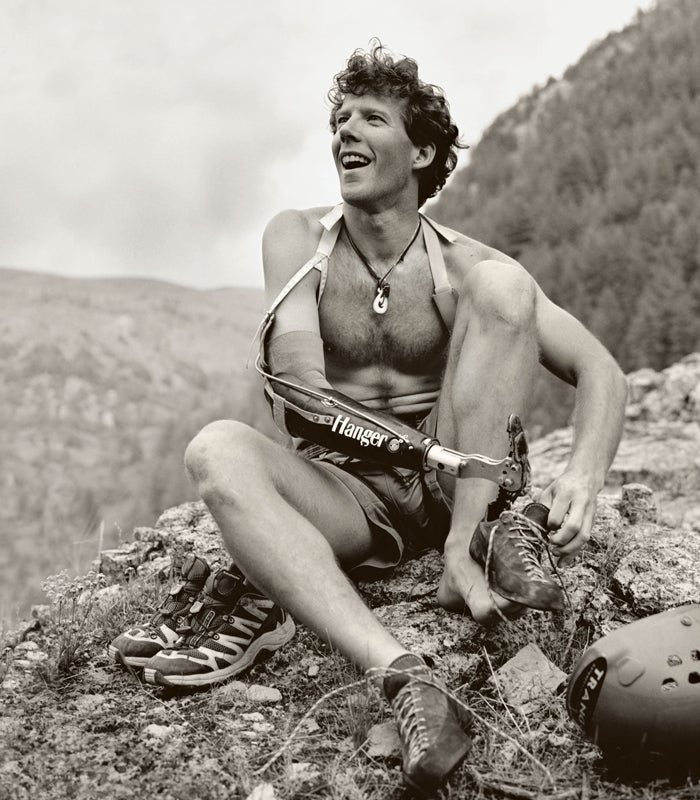

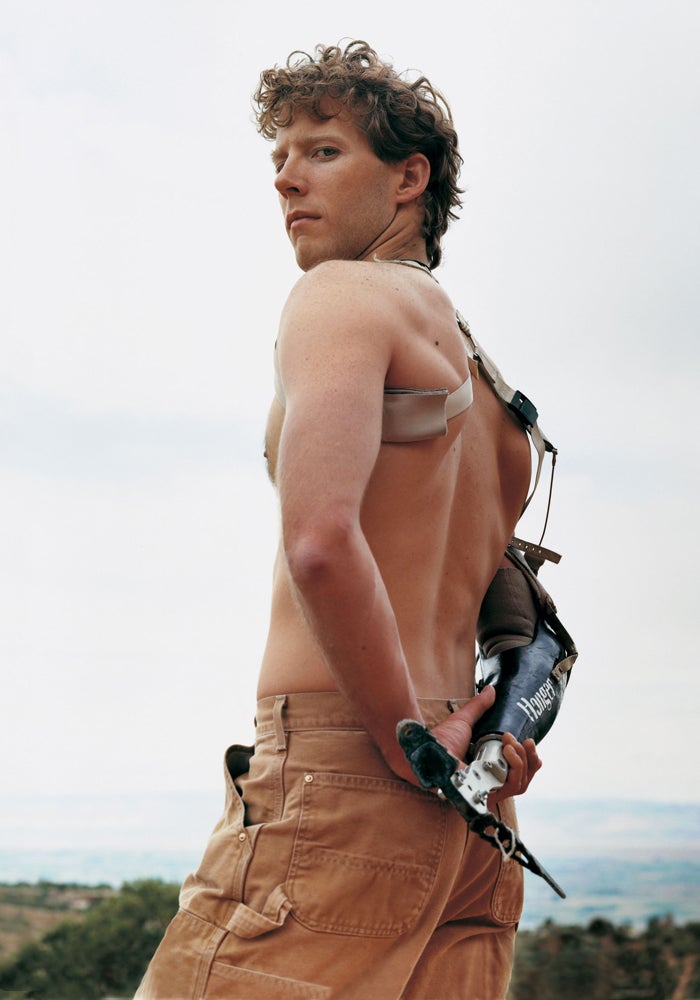

My passion for the wilderness was ignited when I was 12, when my family moved from Indiana to Colorado, in 1987. Back east for college at Carnegie Mellon University, in Pittsburgh, I pined for the West, and after I graduated I took a job at Intel Corporation as a mechanical engineer, in 1997, working in Phoenix, Tacoma, and then Albuquerque. Even before I quit and moved to Aspen, in 2002, to pursue my adventures full-time, I spent every scrap of vacation exploring the remote West; volunteered for three years with the Albuquerque Mountain Rescue Council; and, as my competence grew, embarked on more and more solo expeditions.

I'd recently read two best-selling accounts of extremes in the wilderness, both by Jon Krakauer. Into the Wild, the story of Chris McCandless's dropping out of mainstream society, entranced me. Despite his death in Alaska at age 24, I was inspired with dreams of “rubber tramping” across the country, living out of the back of a truck. As I read Krakauer's next book, Into Thin Air, his chronicle of the 1996 Everest disaster, I wondered what I would have done in those climbers' places. I wanted to reveal to myself who I was: the kind of person who dies or the kind of person who overcomes circumstances to help himself and others.

In 1998, I decided on three climbing projects that would come to occupy my entire recreational focus. I would climb all of Colorado's fourteeners, 59 of them by anyone's highest count; I'd then solo them in winter (something that hadn't been done); and I'd reach the highest point in every state. By the end of 2002, I had climbed the fourteeners, and soloed 36 of them in winter. The further I got with my project, the more I learned about my character. Climbing in winter by myself wasn't just something I did it became who I was.

I pushed myself on increasingly difficult routes, but I also developed strategies to mitigate the added risks of winter travel. Still, there were a few near misses that prompted me to reevaluate my practices. In February 2003, on a backcountry hut trip with some of my Albuquerque Mountain Rescue buddies on Colorado's 11,905-foot Resolution Peak, two of my more experienced friends and I skied a 40-degree bowl, despite dangerous conditions. When we gathered midslope at a cluster of trees, the entire half-mile-wide hillside released with a quiet whoomph. The slide swept us hundreds of feet down the mountain, swamping two of us and burying the third for long minutes, until our avalanche transceivers pinpointed his location. We survived, but our friendships did not. I lost two friends because of the choices we made.

Rather than regret those choices, I swore to myself I would learn from their consequences. Most simply, I came to understand that my attitudes were not intrinsically safe.

3 P.M.

Good Christ, my hand. The flaring agony throws me into a panic. I grimace and growl a sharp “Fuck!” I yank my arm three times in a naive attempt to pull it out from under the rock. But I'm stuck.

“Oh, shit, oh, shit, oh, shit!” I shove against the boulder, heaving against it, pushing with my left hand, lifting with my knees pressed under the rock. I brace my thighs under the boulder and thrust upward, grunting, “Come on … move!”

Nothing.

I'm sweating hard. With my left hand, I lift my right shirtsleeve and wipe my forehead. My chest heaves. I need a drink, but, sucking on my CamelBak hose, I find my water reservoir is empty.

I still have my full Nalgene bottle, but it takes me a few seconds to realize I won't be able to sling my pack off my right arm. Once I shrug my left arm free of the pack strap, I expand the right-side strap, tuck my head inside the loop, and pull the whole thing down my left side, to my feet. Extracting the water bottle, I unscrew the top and, before I realize what I'm doing, gulp three large mouthfuls, then halt to pant for breath. Then it hits me: In five seconds, I've just guzzled a third of my water supply.

“OK,” I say out loud, “time to relax. The adrenaline's not going to get you out of here. Let's look this over, see what we got.” I need to start thinking; to do that, I need to be calm. Poking my left hand into the small gap above the catch point, I touch my right thumb, which is already a sickly gray. It's cocked sideways and looks terribly unnatural. There is no feeling in my right hand at all.

An inner voice explodes at the prognosis: Shit! How did this happen? What the fuck? How the fuck did you get your hand trapped by a fucking boulder? Look at this! Your hand is crushed; it's dying, man, and there's nothing you can do about it. If you don't get blood flow back within a couple hours, it's gone.

“No!” I tell myself out loud. “Shut up, that's not helpful.” It's not my hand I need to worry about. There is a bigger issue. The average survival time in the desert without water is between two and three days, sometimes as little as a day if you're exerting yourself in 100-degree heat. I figure I've got until Monday night.

I take an inventory of my pack. In the outside mesh pouch, I have my CD player, CDs, extra AA batteries, my mini-digital-video camcorder, a digital camera, a three-LED headlamp, and a knockoff of a Leatherman multitool. I've also got a climbing rope and harness and the small wad of rappelling equipment I'd brought to use at the Big Drop rappel. I pull the rope bag out and drop it on the ledge in front of my shins, padding the rock shelf so I can lean into it. My legs are quickly tiring of standing.

My next thought is escape. Eliminating ideas that are just too dumb (like cracking open my AA batteries on the boulder and hoping the acid eats into the chockstone but not my arm), I organize my options in order of preference: excavate the rock around my hand with my multitool knife; rig ropes and an anchor above myself to lift the boulder off my hand; or amputate my arm.

I decide to work on the first option chipping the rock away. Drawing out my multitool, I unfold the longer of the two blades.

My first attempt to saw into the boulder barely scuffs the rock. I try again, pressing harder, but the back of the knife handle indents my forefinger much more readily than the cutting edge scores the rock. Changing my grip on the tool, I hold it like Norman Bates and stab at the rock. Nothing.

It seems like every time I go climbing on a sandstone formation, I break off a handhold, yet I can't put a dent in this boulder. The canyon walls seem to be of a much softer rock. I settle on a quick experiment and, holding my knife like a pen, I etch a g on the canyon's north wall. Slowly, I make a few more letters: e-o-l-o-g-i-c. Within five minutes, I scratch out three more words until I can read the phrase, an elegantly worded warning about falling rocks from Colorado's Thirteeners author Gerry Roach: GEOLOGIC TIME INCLUDES NOW.

8 P.M.

Stress turns into pessimism. Without enough water to wait for rescue, without a pick to crack the boulder, without a rigging system to lift it, I have one course of action. I speak slowly out loud:

“You're gonna have to cut your arm off.”

Hearing the words makes my instincts and emotions revolt. My vocal cords tense and my voice changes octaves:

“But I don't wanna cut my arm off!”

“Aron, you're gonna have to cut your arm off.”

I realize I'm arguing with myself, and yield to a halfhearted chuckle. This is crazy. But I know that I could never saw through my arm bones with either of the blades of my multitool, so I decide to keep picking away at the boulder. Tick, tick, tick … tick … tick, tick. The sound of my knife tapping is pathetically minute.

A breeze is blowing downcanyon, flicking sand over the ledge above me and into my face. I bow my head, and the brim of my baseball cap keeps most of the dust out of my eyes, but I can feel the grit on my contacts.

Darkness seeps from my penumbral hole and spills into the desert. I establish a rhythm, pecking at the rock at two jabs per second, pausing to blow dust away once every five minutes. Time slips past.

Before I know it, it's nearly midnight. Perhaps because of my growing fatigue, a song is playing over and over in my head. Sadly, the melody is from the first Austin Powers movie, which I watched a few nights ago, just a single line of the ending credits' chorus repeating on an infinite loop: BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three, BBC Four, BBC Five, BBC Six, BBC Seven, BBC heaven!

Yeah, that's not annoying at all, Aron.

Even if I wanted to sleep, I couldn't. The penetrating chill of the night air urges me to keep attacking the rock to generate warmth, and when my consciousness does fade, my knees buckle and my weight tugs on my wrist in an agonizing call to attention.

I realize that the best way to conserve my energy is to construct a seat. Getting into my harness is the easy half of the equation. Now comes the hard part: getting some piece of climbing gear hung up on a rock overhead, something that can hold my weight. My first dozen tries fall short, but then, with a brilliantly lucky throw, the carabiner bundle I've rigged hits the wide mouth of the crack, drops into the pinch point, and, with a tug at just the right moment, wedges tight.

A wave of happiness washes over me. With two adjustments of the knots, I can finally lean back and take some weight off my legs. Ahhhhh. Fifteen minutes later, however, my harness begins restricting the blood flow to my legs. I alternately stand and sit, establishing a pattern that I repeat in 20-minute intervals.

In the coldest hours before dawn, I take up my knife again and hack at the chockstone. Just after eight o'clock, I hear a rushing noise filtering down from above. I look up as a large black raven flies over my head. At the third flap, he screeches a loud ca-caw and then disappears from my window on the world. I can see bright daylight on the north wall, 70 feet above. I turn off my headlamp. I've made it through the night.

Day Two: Sunday, April 27, 9:30 A.M.

I wonder what kidney failure will feel like. Not good, probably. Maybe like when you eat so much you get cramps in your back. Only worse, I bet. It's gonna be a rough way to die. Hypothermia would be better. But the temperature didn't dip that low last night, only about 50 degrees on my watch thermometer. Maybe death by flash flood?

But I'm ready for action, not for dying. It's time to get a better anchor established, one that I can use to build a rigging system to try to move the boulder.

It appears to me that a small triangular horn sticks out from a shelf six feet over my head. But my attempts to toss the webbing over the horn founder. Time after time, the webbing pulls free.

A fissure on the right side of the horn catches my eye. The next time I throw, just as the knot is about to crest the horn, I put the rope leader in my teeth and gently twitch the webbing it slips back into the slot. Aha! I slip a metal rappel ring over the yellow strap of webbing, forming a loop with the ring at the bottom.

I've spent two hours just getting the anchor set up, but the endeavor has been an unqualified success so far.

Good work, Aron. Now all you've got to do is move the boulder. Don't stop now.

Cutting 30 feet of climbing rope, I loop one end of the short piece around my chockstone and tie it to itself. Next I thread the other end up through the rappel ring I can just reach it without tugging against my right wrist. I yank on the rope. Nothing.

Well, at least the anchor is holding.

I need a bigger mechanical advantage. Engrossed, I call upon my search-and-rescue experience, and the two hauling systems we used to evacuate people from vertical faces. I decide on a modified Z-pulley system with a haul line so I can pull down to lift the boulder off my hand. I add Prusik loops, wrapping webbing around the rope in a friction knot that, when loose, slides along the rope but tightens when weighted. Then I clip the loops to carabiners, connecting the rope back to itself. With two such changes in direction, I've theoretically tripled the force applied at the haul point. But the boulder ignores my efforts. Flailing through hours of taxing work, I never once budge the rock.

I finally stop for a break and glance at my watch. It's after one o'clock, and I'm sweating and panting.

Suddenly, I hear distant voices echoing in the canyon. My mind swears in exhilarated surprise, and my breath abruptly catches in my suddenly dry throat. Holding my breath, I listen.

“HELP!”

The caterwauling echoes of my shout fade in the canyon. Forcing myself not to breathe, I listen for a reply. Nothing.

“HELLLP!”

The desperation of my quivering shout disturbs me. Again, I hold my breath. After the dying fall of my shout, there is no returningsound besides the thumping of my heart. A critical moment passes, and I know there is no one in this canyon. My hopes evaporate.

My morale slumps in a pang, like the first time a girl broke my heart. Then I hear the noises again. But I know better, and I wait. Slowly they resolve themselves into the scratchy sounds of a kangaroo rat in his nest.

2 P.M.

For the first time, I seriously contemplate amputating my arm. Laying everything out on the surfaces around me, I think through each item's possible use in a surgery. My two biggest concerns are a cutting tool that can do the job and a tourniquet that will keep me from bleeding out. Of the multitool's blades, the inch-and-a-half one is sharper than the three-inch one. It will be important to use only the longer blade for hacking at the chockstone and preserve the shorter one for potential surgery.

Even with the sharper blade, I instinctually understand that I won't be able to hack through my bones I don't have anything that could approximate even a rudimentary saw. The likeliest method available for cutting off my arm, cutting through the softer cartilage of my elbow joint, simply never occurs to me.

I turn my attention to the tourniquet. Experimenting with the hose from my empty CamelBak, I cut the tubing free from the reservoir and manage to tie it in a simple knot around my upper forearm just below my elbow. But I can't cinch it down; the plastic is too stiff.

So much for that idea.

I have a piece of purple webbing knotted in a loop that I untie and wrap around my forearm. A five-minute effort yields a double knot, but the loops are too loose to stop my circulation. I need a stick, or a carabiner, to twist the loops tighter. Clipping the gate of my last unused carabiner through the loops, I rotate it twice. The webbing presses deeply into my forearm and the skin nearer my wrist grows pale. Seeing my makeshift medical setup working brings me a subtle sense of satisfaction.

Nice work, Aron.

Despite my optimism, I realize there's a darker undercurrent to my brainstorming. Until I figure out how to cut through the bones, amputation isn't a practical choice. But I wonder about my courage levels if cutting off my arm becomes a real plan of action. As a test, I hold the shorter blade of the multitool to my skin. The tip pokes between the tendons and veins a few inches up from my trapped wrist, indenting my flesh. The sight repulses me.

What are you doing, Aron? Get that knife away from your wrist! What are you trying to do kill yourself? That's suicide! You'll bleed out. You slice your wrist and it's as good as stabbing yourself in the gut.

I can't do it.

I picture my blood spilled on the canyon walls, the torn flesh and ripped muscles of my arm dangling in gory strands from two white bones pockmarked with divots, the result of my last efforts to chisel through my arm's structural frame. And then I see my head drooped to my sagging torso, my lifeless body hanging from the knife-nicked bones. I set down my knife and retch.

I hate this boulder. I hate it! I hate this canyon. I hate the morgue-cold slab pressing against my right forearm. I hate the faint musty smell of the greenish slime thinly glazing the bottom of the canyon wall behind my legs.

“I … hate … this!” I punctuate each word with slaps of my left palm against the chockstone, as tears well in my eyes.

No expectation has prepared me for this tormenting anxiety of a slow death, thinking about whether it will come tonight in the cold, tomorrow in the cramps of dehydration, or the next day in heart failure. This hour, the next, the hour after that.

But then another voice speaks coolly. That boulder did what it was there to do. Boulders fall. That's their nature. You did this, Aron. You chose to come here today; you chose to do this slot canyon by yourself. You chose not to tell anyone where you were going.

9 P.M.

Night fills the sky. Time swells, my agony expanding with it. I've fallen into a wormhole where I endure excruciating maltreatment for immeasurable eons, only to return to consciousness. In the hazy freedom of my imagination, I fly out of the canyon, dipping and weaving in the whispering clouds over the sea, whitecaps changing to swells as I head still farther west, glancing back to watch the land turn into a green frame around the cobalt ocean.

Day Three: Monday, April 28, 7 A.M.

I still haven't given amputation a full chance.

I realize that I'm not confident in my tourniquet. I need something more flexible than the tubing and more elastic than the … That's it! Elastic! The neoprene tubing insulation from my CamelBak is supple but strong. It's perfect.

I'm elated at the idea and retrieve the discarded tubing insulation from my pack. Why didn't I think of this before? Using my left hand to wrap the thin black neoprene twice around my right forearm two inches below my elbow, I tie a simple overhand knot and tighten with one end in my teeth, then double and triple the knot. I take a carabiner and clip the neoprene, twisting it six times. Clamping down on my forearm, the material pinches my skin. For some reason, the pain pleases me.

I take my multitool and, without thinking, open the long blade. Instead of pointing the tip into the tendon gap at my wrist, I hold it with the blade against the upper part of my forearm. Surprising myself, I press on the blade and slowly draw the knife across my forearm. Nothing happens. Huh. I press harder. Still nothing. No cut, no blood, nothing. Back and forth, I vigorously saw at my arm, growing more frustrated with each attempt. Exasperated, I give up. This is shit! The damn blade won't even break the skin. How the hell am I going to carve through two bones with a knife that won't even cut my skin? God damn it to hell.

That's pathetic, Aron, just pathetic.

Back to waiting.

3:35 P.M.

I have to urinate.

Save it, Aron. Pee into your CamelBak. You're going to need it.

I transfer the contents of my bladder into my empty water reservoir, saving the orangish-brown discharge for the unappetizing but inevitable time when it will be the only liquid I have.

6:30 P.M.

A subtle stirring tells me it's time to pray. I haven't tried that yet. I close my left hand in a loose fist, shut my eyes, and lower my forehead onto my hand.

“God, I am praying to you for guidance. I'm trapped here in Blue John Canyon you probably know that and I don't know what I am supposed to do. Please show me a sign.”

I slowly tilt my forehead back until I'm looking up through the pale twilight. Nothing. What was I expecting? A swirl in the clouds? A petroglyph showing a man with a knife? I start again.

“OK, God, since you're apparently busy … Devil, if you're listening, I need some help here. I'll trade you my arm, my soul, whatever you want. Just get me out of here.”

Day Four: Tuesday, April 29, 5 A.M.

More cycles.

Dark.

Cold.

Stars.

Space.

Shivering.

I've got a little less than three ounces of water left. I place the bottle in my crotch and unscrew the lid. But as I raise the bottle to my mouth, the lid snags on my harness and the bottle slips. My sluggish brain responds too slowly for my hand to catch it before it tilts almost horizontal and a splash of the sacrament darkens my tan shorts, turning the red dust to a patina of shining mud.

Fuck a nut, Aron. Pay attention! Look what you did!

Water is time. By that spill, how many hours did I just lose? Maybe six, maybe ten, maybe half a day? The mistake hits my morale like a train.

6:45 A.M.

I wonder if the police are involved in any theoretical search yet. Perhaps they've obtained my credit-card and debit-purchase histories, which would lead them to Glenwood Springs, Moab, and then Green River. No, wait: I paid cash for those Gatorades in Green River. Damn.

Credit, debit, cash, it doesn't matter; a couple energy drinks aren't going to guide rescuers all the way out here. Shifting away from the dim hopes of my rescue, I conjure up a series of bright memories that bring me a tidal change of emotion. I am surprisingly happy. Rejuvenated, I start videotaping.

“It's 6:45 in the morning on Tuesday morning,” I repeat myself. “Mom, Dad, I really love you guys. Thank you both for being understanding and supportive. I really have lived this last year. I wish I had learned some lessons more astutely, more rapidly, than what it took to learn. I'll always be with you.”

My thoughts turn to my sister and her wedding to her fiancé, Zack Elder, in August. “I wanted to say to Sonja and Zack that I really wish you the best in your upcoming life together. Do great things with your life that will honor me the best. Thanks.”

Thinking about my sister makes me happy. She's planning to be a volunteer teacher; it reassures me to know she's got such great aspirations. A smile cracks my dry lips.

7:58 A.M.

Slowly, I become aware of the cold stare of my knife. There's a reason for everything, including why I brought that knife, and suddenly I know what I am about to do. Mustering my courage, I dismantle a purple Prusik loop from the rigging and tie it around my right biceps, preparing the rest of my tourniquet as I refined it yesterday.

Unfolding the shorter blade, I close the handle and grasp it in my fist. Raising the tool above my right arm, I pick a spot on the top of my forearm. I hesitate, jerking my left hand to a halt a foot above my target. Then I recock my tool and, before I can stop myself, my fist violently thrusts the blade down, burying it to the hilt in the meat of my forearm.

“Holy crap, Aron,” I say out loud. “What did you just do?”

My vision warps with astonishment. I bend my head to my arm, and my surroundings leave sepia-toned hallucinogenic trails behind them. Yesterday, it didn't seem possible that my knife could ever get through my skin, but I did it. When I grasp the tool more firmly and wiggle it slightly, the blade connects with something hard, my upper forearm bone. I tap the knife down and feel it knocking on my radius.

Whoa. That's so bizarre.

I am suddenly curious. There is barely any discernable sensation of the blade below skin level. My nerves seem to be concentrated in the outer layers of my arm, then. I confirm this by drawing the knife out, slicing up at my skin from underneath. Oh, yeah, there they are. The flesh stretches with the blade, broadcasting signals through my arm as I open an inch-wide hole. Letting the pain dissipate, I note that there is remarkably little blood; the capillaries must have closed down for the time being. Fascinated, I poke at the gash with the tool. Ouch.

As I root around, burgundy-colored blood seeps into my wound. I tap at the bone again, feeling the vibration of each strike through my left thumb and forefinger. Even damped by surrounding tissues, the hollow thumping of the blade against my upper forearm bone resonates up into my elbow. The soft thock-thock-thock tells me I have reached the end of this experiment. I cannot cut into or through my forearm bones.

Sweating from the adrenaline, I pick up my water bottle. As the first drops splash against my lip, I open my eyes and stare into its blue bottom with detached observation as I continue to tilt the bottle up and up. I'm going to do it, and the fact I shouldn't makes me enjoy it even more.

Just do it get it over with. It doesn't matter.

Each tablespoon of water satisfies me like a whole mouthful, and instantly I'm gulping at the dribbling flow. I close my eyes … Oh, God. I swallow the last drops and it's gone.

Day Five: Wednesday, April 30, 3 A.M.

In the piercing brutality of night, I repeatedly escape into trances. If heaven turns out to be as comfortable as the trances, then what I return to in the canyon is nothing short of hell. There is only one emotion in hell: unmitigated despair wrapped in abject loneliness, and I am enveloped in it.

9 A.M.

I update my hour tallies in my head: 96 hours of sleep deprivation, 90 hours that I've been trapped, 29 hours that I've been sipping my urine, and 25 hours with no fresh water. The exercise evokes no emotion, only matter-of-fact acknowledgment.

Suddenly, I have a new idea what about using a rock as a wrecking ball to smash into the chockstone? Or maybe this is an old idea. Have I thought of this already? I can't remember.

2 P.M.

“It's Wednesday afternoon,” I say into the camera. “Some logistics still to talk about.” I've covered what to do with my possessions, so now I begin talking about where I'd like my remains to be scattered Big Sur, Havasupai Creek in Arizona, New Mexico's Sandia Peak, a little spot on the Rio Grande …

Looking straight into the lens, I bid one last adieu: “I'm holding on, but it's really slowing down, the time is going really slow. So again, love to everyone. Bring love and peace and happiness and beautiful lives into the world in my honor. It would bestow the greatest meaning for me. Thank you. I love you.”

Somewhere inside my mind, I know I won't survive tonight in Blue John Canyon. The day has been cool; this night will be the worst yet. It's not something I debate or internally discuss, but when I consider that I am going to die in a matter of hours, it rings true. If my time is up, then it is up, and yet I have a disconnected feeling of lightheartedness that vaguely approximates bliss. I wonder if this is what rapture feels like. Give it whatever name I want all I know for sure is that I don't have to sweat it out anymore, because I'm not in charge.

11 P.M.

The canyon is an icebox. These are the killing winds.

I only get through two of the frigid nine hours of darkness before I decide it is time to make a final annotation. My watch confirms that it is April 30, for another hour at least. Above the four letters of my name, ARON, I scratch into the red rock, OCT 75. Below my name, I make the complementary scratching: APR 03.

I lean back in my harness and slip into another trance. Color bursts in my mind, and then I walk through the canyon wall, stepping into a living room. A blond-haired three-year-old boy in a red polo shirt comes running across a sunlit hardwood floor in what I somehow know is my future home. By the same intuition, I know the boy is my own. I bend to scoop him into my left arm, using my handless right arm to balance him, and we laugh together as I swing him up to my shoulder.

The boy happily perches on my left shoulder while I steady him with my left hand and right stump. Smiling, I prance about the room, tiptoeing in and out of the sun dapples on the oak floor, and he giggles gleefully. Then, with a shock, the vision blinks out. I'm back in the canyon, echoes of his joyful sounds resonating in my mind. Despite having already come to accept that I will die where I stand before help arrives, now I believe I will live.

That belief, that boy, changes everything for me.

Day Six: Thursday, May 1, 9:30 A.M.

With five days of gritty buildup pasted to my contact lenses, my eyes hurt at every blink, and wavering fringes of cloud frame my dingy vision. Sip after sip of acidic urine has eroded my gums and left my palate raw. I can't hold my head upright; it lolls off to lean against the canyon wall. I am a zombie. I am the undead.

Miserable, I watch another empty hour pass by. The boost I felt from my vision of the boy has dissipated entirely. I have nothing whatsoever to do. I have no life. There is nothing that gives even a slight hint that this awful stillness will break. But I can make it break. I can resume smashing the chockstone with the rock.

Bonk! Again, I strike the boulder, the pain in my hand flaring. Thwock! And again. Screeaatch! My rage blooms purple amid a small mushroom cloud of pulverized grit. I bring the rock down again. Carrunch! Now my voice stokes hatred for the chockstone as I growl with animalistic fury “Unnngaaarrrrgh!” in response to the throbs pulsing in my left hand.

Whoa, Aron. You might have taken that too far.

With my knife, I begin clearing particles from my trapped hand, using the dulled blade like a brush. Sweeping the grit off my thumb, I accidentally gouge myself and rip away a thin piece of decayed flesh. It peels back like the skin of boiled milk before I catch what is going on. I already knew my hand had to be decomposing without circulation, but I wasn't sure how fast the putrefaction had advanced. Now I suddenly understand the indigenous insect population's increased interest in my hand.

Out of curiosity, I poke my thumb with my knife blade twice. On the second prodding, the blade punctures the epidermis, like it is dipping into a stick of room-temperature butter, and releases a telltale hissing. Escaping decomposition gases are not good; the rot has advanced more quickly than I guessed. Though the smell is faint to my desensitized nose, it is abjectly unpleasant, the stench of a far-off carcass.

I lash out in fury, trying to yank my arm straight out from under the sandstone handcuff, never wanting more than I do right now to simply rid myself of any connection to this rotting appendage.

I don't want it.

It's not a part of me.

It's garbage.

Throw it away, Aron. Be rid of it.

I thrash myself forward and back, side to side, up and down, down and up. I scream out in pure hate, shrieking as I batter my body against the canyon walls, losing every bit of composure that I've struggled so intensely to maintain. And then I feel my arm bend unnaturally in the unbudging grip of the chockstone. An epiphany strikes me with the magnificent glory of a holy intervention and instantly brings my seizure to a halt:

If I torque my arm far enough, I can break my forearm bones.

Like bending a two-by-four held in a table vise, I can just bow my entire goddamn arm until it snaps in two!

Holy Christ, Aron, that's it, that's it. THAT'S FUCKING IT!

There is no hesitation. I barely realize what I'm about to do. I unclip from the anchor webbing, crouching until my buttocks are almost touching the stones on the canyon floor. I put my left hand under the boulder and push hard, harder, HARDER! to put a maximum downward force on my radius bone. As I slowly bend my arm down to the left, a POW! reverberates like a muted cap-gun shot.

I scramble to clear the chockstone, trying to keep my head on straight. Without further pause and again in silence, I hump my body up over the rock. Smearing my shoes against the canyon walls, I push with my legs and grab the back of the chockstone with my left hand, pulling with every bit of ferocity I can muster, until a second cap-gun shot ends my ulna's anticipation. Sweating and euphoric, I touch my right arm again. Both bones have splintered in the same place, just above my wrist.

I am overcome with excitement. Hustling to deploy the shorter and sharper multitool blade, I completely skip the tourniquet procedure I have rehearsed and place the cutting tip to my wrist, between two blue veins. I push the knife into my wrist, watching my skin stretch inward, until the point finally pierces and sinks to its hilt.

In a blaze of pain, I know the job is just starting.