Entertainment

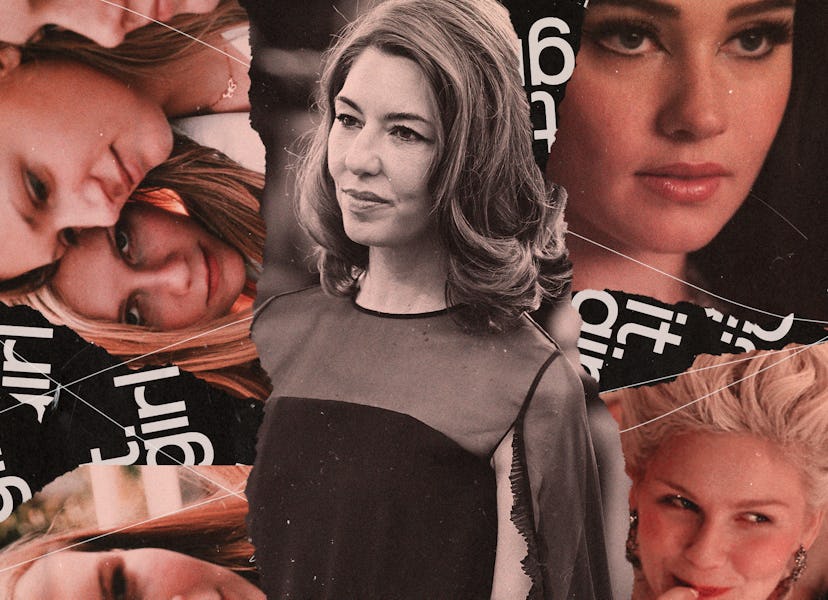

Sofia Coppola Knows What Makes An It Girl

The Priscilla director — once a “girl of the moment” herself — has spent her film career analyzing women who both captivate and mystify us.

Before Sofia Coppola was an Oscar-winning filmmaker, she was an It Girl. You can see it in a 1994 archival video from MTV, where she and then-boyfriend Spike Jonze talk about staging a guerrilla fashion show for Sonic Youth frontwoman Kim Gordon's X-Girl clothing label. “You too, can do a fashion show,” she says, giggling into the microphone. “That’s all you need: walkie-talkies and a sheet and some girls.” It helped that she had good genes — her parents are filmmakers Eleanor and Francis Ford Coppola, the latter best known for directing The Godfather trilogy — great style, and hip friends. But the ease with which she could whip together a cultural moment and seize attention was her real gift. That same year, Coppola would launch her own clothing line, Milk Fed. "Girl-of-the-moment Sofia Coppola has turned herself into a designer,” W reported.

Today, Milk Fed is largely forgotten and her acting career — including a much-criticized performance in The Godfather Part III — never coalesced into a real passion. But in making movies, she has turned her eye again and again to other girls-of-the-moment across eras who share her je ne sais quoi and, in their own ways, conjure a mix of mystery, fascination, and even envy. This is true of her feature debut, a 1999 adaption of Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides, and it’s true of her most recent film, Priscilla, about Priscilla Presley, former wife of Elvis. (It hits select theaters this Friday before its wide release on Nov. 3.) From those films, through Lost in Translation and Marie Antoinette and The Bling Ring, Coppola has tried to both understand and further mythologize women who captivate us.

“I know that growing up, people are looking at you in a different way,” she told The Hollywood Reporter of coming from a showbiz family. And because Coppola so deeply understands what it means to be gazed upon, she also knows how to gaze herself: Her characters often have few words to offer and hide behind the facades they create for themselves — or have been created for them. But even in their silence and glamour, they can contain worlds.

Sofia Coppola in 2000, before the premiere of The Virgin Suicides.

The Virgin Suicides is all about those inner worlds. Set in 1975, it is told from the perspective of the men who are entranced by the Lisbon sisters, five beautiful blonde girls who bristle under their Catholic parents’ strict watch and all eventually kill themselves. “Now, whenever we run into each other at business lunches or cocktail parties we find ourselves in the corner going over the evidence one more time,” begins the narrator, speaking from the present. “All to understand those five girls, who after all these years we can’t get out of our minds.”

The film is a statement about the allure and the danger of unknowability — what gets lost when you’re deciding what you see. It’s a theme Coppola would explore more literally in her movies in which viewers encounter subjects with a certain amount of notoriety already. Coppola doesn’t judge them; she’s more interested in why young women covet and what pushes them to excess. Marie Antoinette, a quasi-biopic doused in pastels and a new wave soundtrack, offers a look at the scared girl who came to embrace the pleasures of the often-stifling French court only to be vilified in turn. The young criminals in The Bling Ring, which lightly fictionalizes the string of late-2000s break-ins at celebrity homes, are products of the era’s tabloid culture. They figure if they can’t be Paris Hilton, they can live her life.

Because Coppola so deeply understands what it means to be gazed upon, she also knows how to gaze herself.

Priscilla has less infamy but all the familiar yearning. Based on the book Elvis and Me, written by Presley along with Sandra Harmon, Priscilla is a portrait of a teenage girl swept into the world of celebrity and molded into an icon, even as she chafes against the world she so longed to enter. It opens with a 14-year-old Priscilla, played by Cailee Spaeny, unmade-up at a soda shop in West Germany where her mother and military stepfather are stationed. A man approaches and begins asking her about herself. It’s the kind of uncomfortable interaction pretty girls are used to having. But he comes with an offer: He wants to invite her to a party at Elvis Presley’s house.

After that fateful night, the movie charts the unfolding of Elvis (Jacob Elordi) and Priscilla’s relationship in ways that are romantic for her, but deeply uncomfortable for the viewer, who can better grasp the line between infatuation and manipulation. Priscilla’s wants are both material and emotional: She begs her parents to let her go to Graceland, but once she gets there, it becomes — much like Lisbon girls’ house — a place of restriction. Elvis won’t allow her to get a job for herself, and he starts choosing how she dresses and does her makeup. The portrait of Priscilla that echoed throughout time — a mane of black hair and thick cat-eye — was one of his invention.

She alternately wilts and thrives through his gaze. When he tries to cage her, she bristles. But Priscilla also knows how to play his arm candy among his friends in Las Vegas. When he is showering her with love, Spaeny seems to literally brighten, preening as Elvis takes pictures of her or records her on a home video. Priscilla, the movie suggests, understands the power of an image to get what she wants, even when it’s clear that looking good and feeling good are not the same.

Coppola also knows what the lens of a camera can do. The W story about her fashion-line launch features an image of her at 22, seductively on her side, flanked by her friends, among them Zoe Cassavetes, another daughter of film royalty. She offered an idea of herself for the lens that spoke to what people projected on her already: savvier and cooler than you are. In Coppola’s world, It Girls are born when perception and reality collide, forever playing with the concepts of what we wish them to be.

Too often throughout her career, Coppola’s critics have dismissed her work as favoring aesthetics over substance. The images she brings to life through her person or on screen are tantalizing, and she relishes in their beauty. It can be tempting to get distracted by that, which is perhaps the whole point: These women — be they Coppola, or the Lisbon sisters, or Priscilla — are all in some capacity aware of the power of their images, and they wield that power to disarm before they show us who they are.

This article was originally published on