Scientist of the Day - Robert Bunsen

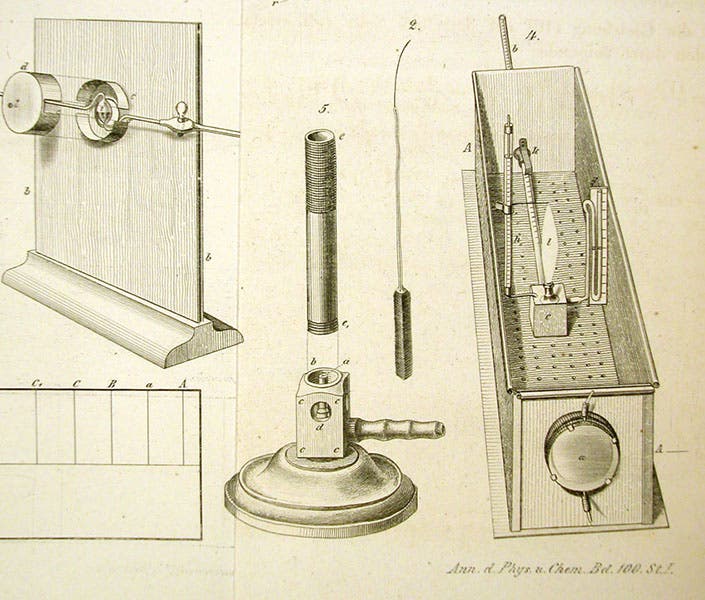

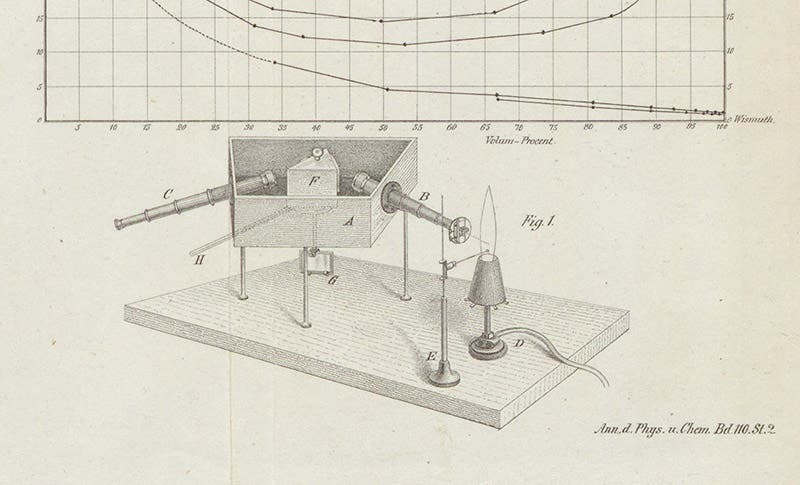

Robert Bunsen, a German chemist, died Aug. 16, 1899, at age 88. Bunsen taught at several German universities, such as those in Göttingen, Kassel, Marburg, and Breslau, before accepting a professorship at the Univefsity of Heidelberg in 1853, where he remained for the next 36 years. In Heidelberg, Bunsen worked with a young English student, Henry Roscoe, to tackle problems of photochemistry, a new field that developed rapidly in the wake of the invention of photography in 1839. A photograph (second image) shows Bunsen (seated), Roscoe (right), and Bunsen’s future collaborator, Gustav Kirchhoff (left). Why Bunsen was seated will become apparent when you view the fourth image.

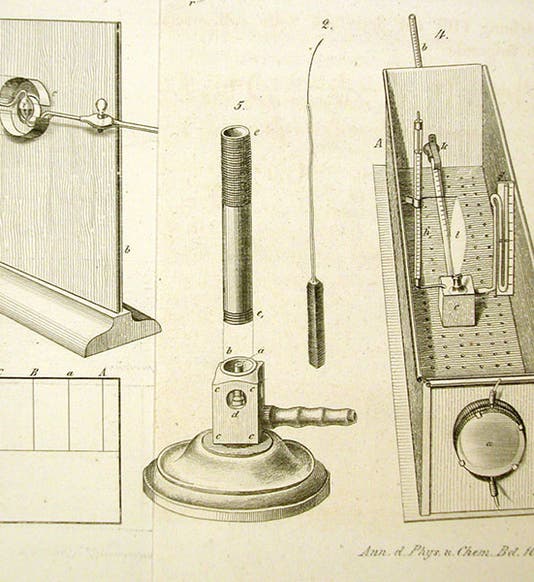

It was just about this time that coal-gas was made available at German universities, and it was a real boon to the chemical laboratory to have a ready and controllable source of heat. However, the gas burners available tended to create more light than heat, and were somewhat sooty as well, which was a problem in the lab. So Bunsen and his machinist, Peter Desaga, set out to create a burner that would provide a hot, smokeless, flame. They succeeded in 1855 with the now famous Bunsen burner, which had adjustable openings at the bottom to regulate the flow of oxygen to the flame. The burner was first pictured in 1857 (first image) as part of an article by Bunsen and Roscoe, "Photochemische Untersuchungen," in the journal Annalen der Physik., which we have in our serials collections.

Also in 1857, Bunsen published a book, Gasometrischen Methoden, which set down the basic principles of gas analysis, how to collect, measure, and analyze gases. It is one of the milestones of chemistry. Although Roscoe left Heidelberg that year to take up a position at the University of Manchester (see our post on Roscoe), he seized the opportunity to translate Bunsen's book into English. Roscoe’s translation, Gasometry, was published in London in 1857 at almost the same time as Bunsen’s German text appeared in Braunschweig. We have both versions in our history of science collections.

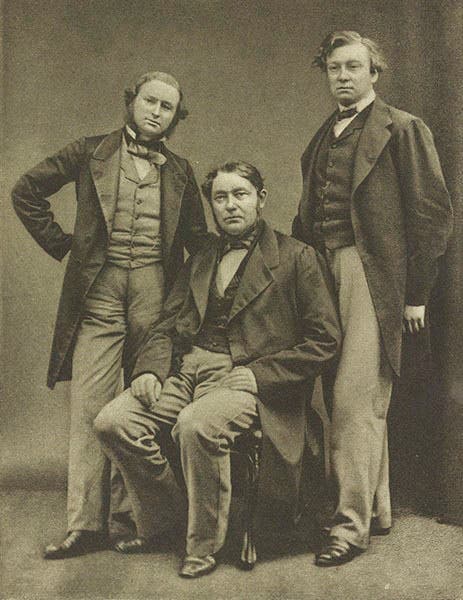

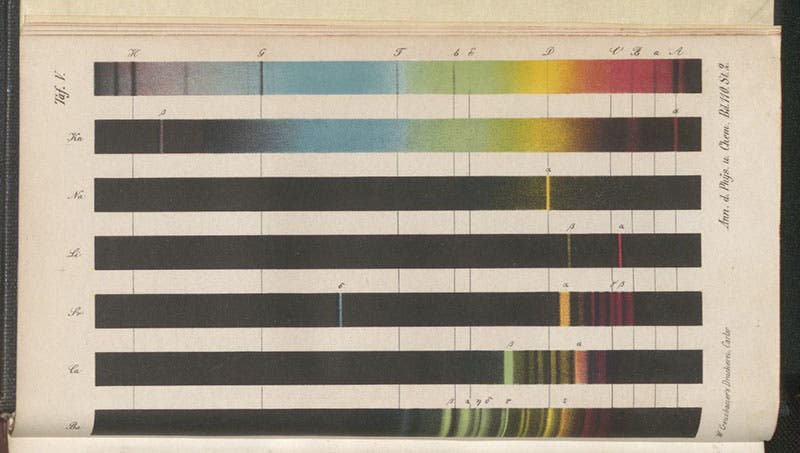

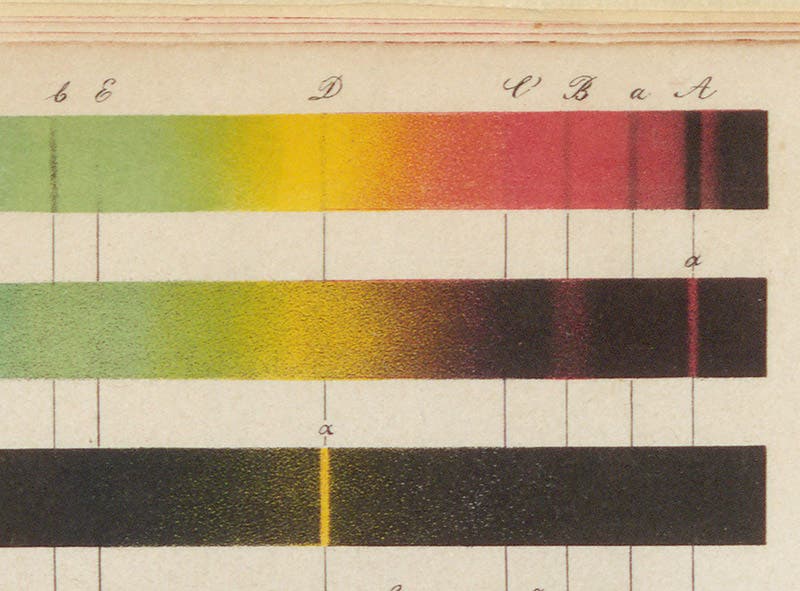

In 1859, Bunsen teamed up with Gustav Kirchhoff to study the spectra of chemical elements. They devised a way to vaporize various elements in a Bunsen burner and then pass the emitted light through a prism, which spread the light out into a spectrum. In effect, they invented the spectroscope, and spectroscopy (third image). They found that instead of a continuous spectrum, burning hydrogen produces four narrow lines of four different colors (wavelengths)., while sodium vapor emits only two yellow spectral lines, very close together. Each element, in fact, has characteristic spectral lines that can be used to identify that element. Since it was known that the solar spectrum is crossed with hundreds of dark lines, this suggested that the solar spectrum contains the chemical signatures of all the elements that make up the Sun.

Bunsen and Kirchhoff published the results of their work in an article (title translated), “Chemical analysis through spectroscopy,” in the Annalen de Physik und Chemie in 1860, which we have in our serials collection. We show one of the chromolithographs that presents the spectra of various elements, such as sodium in the third line, as well as the dark-line solar spectrum at the top (fifth image). A detail shows how the double-yellow line of sodium matches up with a prominent dark line (the “D” line) in the solar spectrum (sixth image).

The discovery that compounds could be analyzed and elements identified through spectroscopy was truly a revolutionary one, which profoundly affected both chemistry and astronomy. Indeed, astrophysics – the study of the stars as physical, chemical bodies – is said to have begun with the work of Bunsen and Kirchhoff.

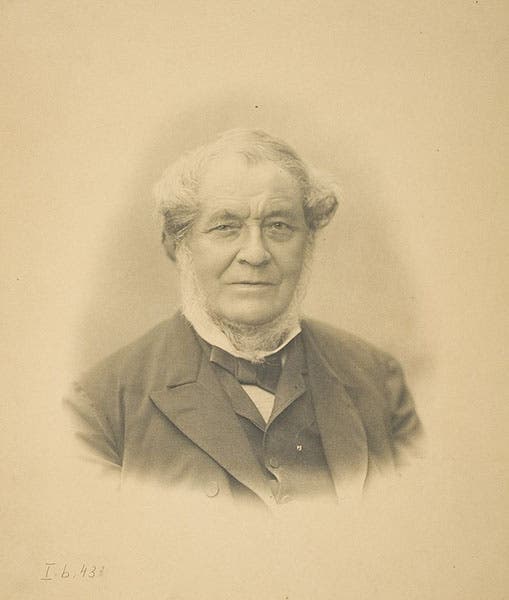

By all accounts, Bunsen was a congenial soul who was revered by all his students and colleagues. A photograph of an affable older Bunsen would seem to bear that out (seventh image). Bunsen is buried in Bergfriedhof cemetery in Heidelberg, where his grave is an object of pilgrimage for more than a few modern-day chemists (eighth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.