by Scott W. Michael

Excerpt from CORAL Magazine, September/October 2020

My first encounter with a dartfish in the wild happened unexpectedly in a shallow lagoon on the Great Barrier Reef. I was snorkeling in just two meters (seven feet) of water when I came across a shoal of about 20 elongate, light green fish. They were hovering above the sand, and as I approached, very slowly, they began to form a tighter group and drifted towards the bottom. Suddenly, with incredible speed and synchronized agility, the whole group vanished into a small burrow in the substrate.

The fish that I had seen miraculously disappear before my eyes were Green Dartfish (Ptereleotris microlepis), a species with a widespread range across the Indo-Pacific. When I returned home to Nebraska, I was determined to acquire some of these beauties for my home aquarium. That was almost four decades ago and while members of this family were sporadically available then, their popularity has greatly risen over the years. The main reason for this is because they are ideally-suited for reef aquariums—safe with corals, hardy, and relatively small, usually not exceeding about 13 cm (5 in,) in length. Here I would like to take a closer look at the genus Ptereleotris, unpacking both their natural history and its relationship to their husbandry needs. While I concentrate on those species that make regular appearances in marine aquarium shops, we will also dream a little and take a look at some less-often-seen types.

Range and Relationships

The 21 species of described Ptereleotris are virtually circumtropical: they occur in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean, throughout the Pacific, including the tropical eastern Pacific, and the Western Atlantic and Caribbean. Those genus members in the Eastern Pacific (one species present) and tropical Western Atlantic (three described species) were once placed in a separate genus, known as Ioglossus, but have since been merged into the genus Ptereleotris.

Ptereleotris microlepis, Green Dartfish, cluster near and within a sandy burrow, where they can disappear in an instant when a predator approaches. New Caledonia. Ptereleotris microlepis, Green Dartfish, cluster near and within a sandy burrow, where they can disappear in an instant when a predator approaches. New Caledonia. Image: Gerald R. Allen.

This a group of fishes that has been in a bit of taxonomic turmoil for a number of years. Along with six other genera, the dartfishes helped comprise the subfamily Ptereleotrinae, and were originally placed in the family Gobiidae (the gobies). They were then moved to the family Microdesmidae (the wormfishes). Finally, the members of this subfamily were cleaved from the microdesmids and placed in their own family: the Pterelotridae. Depending which authors you read (and how old the manuscript happens to be), you will find them placed in any one of these three family groups. While there is still some debate on their systematic status, the preeminent authorities on these fishes, Dr. Helen Larson and Dr. Doug Hoese, both in Australia, consider the family Ptereleotridae to be valid. Does your brain hurt yet? Even the common or vernacular names applied to group are varied and confusing, including dartfishes, dart gobies, dartgobies, gudgeons, “gudgeon-gobies,” and even “gliders.”

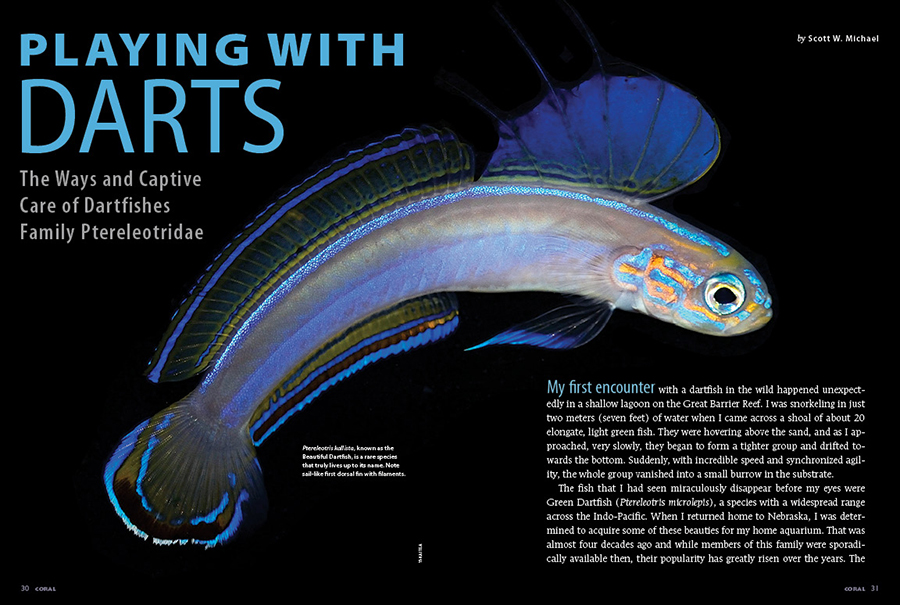

However we choose to classify them and wherever they occur, all members of the genus are relatively diminutive fishes, with slender, torpedo-shaped bodies, a small blunt head, large eyes and a protruding lower jaw. All but one of these dartfishes have a dorsal fin that is divided into a spinous anterior section and a soft posterior portion. In several species the first dorsal fin is sail-like, with filamentous ornamentation. It has been suggested that in at least one species, Ptereleotris hanae, the Threadfin Dartfish, males possess streamers extending from the anterior part of the dorsal fin and the tail, but this is not based on internal examination of gonads or confirmed by observations of reproduction. Just prior to spawning, the female dartfishes will swell with hydrated eggs, but this is, of course, a very transitory sexual difference. None of the species has been shown to display sexual dichromatism.

Dartfish Biology

The dartfishes hover above sand, rubble or reef pavement, moving up to two meters (seven feet) above the bottom. They often live in habitats that are current prone, depending on water movement to provide access to their zooplanktonic prey. Most are abundant in relatively shallow water, but there is at least one species, Ptereleotris lineopinnis, known as the Sad Dartfish, that has only been collected from water deeper than 90 m (290 ft.). Juveniles of many Ptereleotris spp. occur in groups, while adults frequently live in pairs—one unique behavioral characteristic of the group. In some species, these pairs live in close proximity to one another, so that they form large colonies. There are a few deepwater species (Ptereleotris caeruleomarginata, P. grammica and P. uroditaenia) that are not infrequently found singly, but they too occur in pairs.

When threatened by a predator, those dartfishes that form groups, such as the Green Dartfish (P. microlepis) that were my first acquaintances in Australia, will employ different evasive strategies which are dependent on the size of the dartfish group. If the group is small, say less than 20 individuals, it will break-up into smaller units which descend towards the entrances where they refuge. They hover just above the entrance until the predator comes too close, at which time they dive into the burrow. In contrast, individuals comprising larger groups (i.e., from 30 to 150 dartfish), will move closer together and, as a shoal, slowly swim away from the threat.

Typical dartfish behavior, sharing a burrow with an Amblyeleotris shrimp goby. Image: Scott W. Michael.

The burrows the dartfishes refuge in are typically those constructed by crustaceans, mollusks, worms or other fishes. In some areas, they regularly share a refuge with pistol or snapping shrimps (Alpheus spp.) and their shrimp-goby associates (e.g., Amblyeleotris, Cryptocentrus and Stonogobiops) or with sleeper gobies (Valenciennea spp.). When they live with a goby and pistol shrimp, they do not communicate with the crustacean in the same way that the gobies do (i.e., antennae-to-tail communication), but they may provide some benefit to their burrow mates by serving as an early warning system. The dartfish, which spends much of its time higher in the water column, may see an approaching menace long before the sentinel goby does. As the threat approaches, the dartfish begins moving toward the shared burrow, warning the goby and shrimp of imminent peril and stimulating greater goby vigilance. If the dartfish dashes for the burrow, the goby and shrimp will typically beat the ptereleotrid into hiding or be right on its tail! Less frequently than “freeloading” in another animal’s burrow, dartfishes will dig their own home, making a depression under a rock or piece of rubble by displacing the sand with rapid undulations of their tails (this behavior may be more likely to occur in captivity where appropriate hiding places are in short supply as compared to the wild).

No data exists on the sexuality of the dartfishes (e.g., are they gonochorists or hermaphrodites?) and little information is available on their reproductive behavior and mating systems. However, many species apparently form long-term pair-bonds. Dartfishes lay demersal eggs in the burrows in which they refuge, and upon hatching the larvae enter the plankton to drift and develop without further parental attention. The juveniles settle-out of the plankton at about 2.5 cm (1 in.), at which time, many species will immediately form schools for protection.

Dartfish Husbandry

Fortunately, figuring out the husbandry needs of members of the genus Ptereleotris is not as confusing as working out their classification status. Most of the dartfishes will fare well in a peaceful community setting, especially if the tank is placed in relatively calm surroundings. Because of the small sizes attained by the Ptereleotris spp., they can be housed in spaces as modest as a 50-gallon (200-L) aquarium. Of course, to keep larger groups of dartfishes, you will need a more spacious tank (and, as discussed below, I certainly would recommend keeping most species in groups).

Ptereleotris evides is known as the Blackfin or Scissortail Dartfish, which typically occurs in pairs. It is more likely to swim away from a threat rather than dash into its burrow. Raja Ampat Islands, West Papua. Image: Scott W. Michael.

The dartfish aquarium should have plenty of open space, with a sand bottom, and several flat rocks laying on the substrate. You can excavate a depression in the sand and lay a rock over it, or let them dig their own holes. In order to facilitate hiding place construction, a sand bed depth of at least 8 cm (3 in.) is a good idea. Piles of rubble, of varying size, will provide appreciated crevices. If you want to go with a more manmade approach to burrow construction, take lengths of 1-inch-diameter PVC pipe, with a cap on one end and a 45 degree elbow on the other, and bury these under the substrate, so the opening of the elbow is just above the substrate surface. This will provide ready-made burrows for these fish. A quick suggestion to aquarium store owners: these burrows can be very useful when trying to remove dartfish for resale. Just lift the artificial hiding place out of the tank and gently pour its contents into a fish bag. I have had dartfishes bury themselves in finer sand substrates at night or when they were threatened, when suitable shelter sites were not available.

The Ptereleotris spp. are some of the most peaceful aquarium fishes available and most do best when housed with members of their own kind or even in heterospecific aggregations. In fact, three of most ubiquitous aquarium species, the Spottail Dartfish, the Green Dartfish, and the Zebra Dartfish (Pterelotris heteroptera, P. microlepis and P. zebra, respectively) do best if kept in groups of six or more. Many of the other Ptereleotris spp. typically occur in pairs in the wild (at least as adults), but multiple pairs of these types can be housed in a large reef aquarium (135 gallons [500 L] or more) if sufficient hiding places are provided.

Social Chemistry

Selecting tankmates for your dartfish is one of the keys to their successful husbandry. The perfect community setting is one that contains other peace-loving types. This may include grammas, assessors, small reef basslets, cardinalfishes, leopard wrasses (Macropharyngodon), possum wrasses (Wetmorella), lyretailed fang blennies (Meiacanthus), dragonets, many goby species, firefishes (Nemateleotris), wormfishes, tobies (Canthigaster) and boxfishes. While some anthias can be hard on dartfishes (e.g., Pseudanthias rubrizonatus, P. squamipinnis), some of the more passive species (e.g., Pseudanthias lori, P. parvirostris, P. smithvanizi, P. ventralis), which are best kept by more seasoned aquarists, are acceptable dartfishes tankmates. The more diminutive jawfishes (e.g., Opistognathus aurifrons) are not usually considered to be aggressive in the aquarium, but they have been known to evict dartfishes from shared burrows, so make sure these shelter sites are not in short supply if you choose to keep these species together.

Dither fishes, that is bolder species that spend most of their time swimming about the water column, are excellent to induce confidence in these shy fishes and assist acclimation. One of the most popular dither species are damsels in the genus Chromis. A group of, say, a half dozen Blue-Green Chromis (Chromis viridis) are an excellent choice if the tank is large enough. (Note: these fish are very susceptible to the ciliate parasite Uronema marinum, so make sure you quarantine them properly before adding them to your reef display tank. They also grow to 10 cm (4 in.) in length and need ample swimming room.) Vanderbilt’s Chromis (Chromis vanderbilti) is another good dither fish choice for the Pacific dartfish aquarium, or if you are looking to create a Caribbean biotope, you can house your Atlantic dartfish with a groups of juvenile Sunshine Chromis (Chromis insolatus). Note—this later species can reach 16 cm (6.3 in.) in length, undergoes a radical color change, changing from bright and shiny, to rather dull and it is possible that larger individuals may chase dartfish.

If you place dartfishes in with more pugnacious sorts, they are likely to hide incessantly, not eat or jump out of the tank. Species that are likely to cause problems include angelfishes, including pygmy angels, dottybacks, many damselfish species (exception as indicated above are the Chromis), aggressive hawkfishes, large wrasses (e.g., Thalassoma), surgeonfishes and triggerfishes. There are also fish that are rarely aggressive toward heterospecifics that have been known to bully dartfishes. For example, I have had the relatively innocuous Longnose Hawkfish (Oxycirrhites typus) nip at and injure these fishes on a number of occasions. Even fairy wrasses (Cirrhilabrus), which are not known aquarium tyrants, will sometimes harass newly introduced dartfishes, causing frequent hiding bouts. If you are going to keep ptereleotrids with tankmates that could potentially be problematic (such as fairy wrasses), be sure the dartfish are introduced to the aquarium first and well established before adding a potential bully. In fact, it is possible to keep a group of dartfishes (e.g., Ptereleotris zebra) in very large reef aquarium with some of the more boisterous fish species if they are given plenty of time to acclimate and lots of hiding places before their more malevolent neighbors are added. For example, I had one maintenance account with a group of P. zebra in a 400-gallon (1,500-L) tank with larger angels, rabbitfishes, surgeonfishes and a porcupinefish. Of course, morays, lizardfishes, frogfishes, groupers, snappers, jacks and larger hawkfishes (e.g., Paracirrhites) are likely to eat these fishes, even if the dartfish is as long as the predator. Long, slender fish like the Ptereleotris roll up nicely in the stomach of such piscivores.

Trio of Ptereleotris heteroptera, is known in the aquarium trade as the Blue or Spot-tail Dartfish, in classic hovering formation. Dartfishes are capable of rapid dashes and are notorious for jumping from the aquarium if startled or harassed. Image: Gerald R. Allen.

While dartfishes are great for the reef aquarium, because they do not harm corals in anyway, they may be eaten by some invertebrates. Carnivorous crabs (including more robust hermits), Green Brittle Stars (Ophiarachna incrassata), pencil urchins and strong stinging anemones, like carpet anemones (Stichodactylus) and fire anemones (Actinodendron), may prey upon ptereleotrids.

Dartfishes are micro-predators that should be provided with a varied diet suitable for zooplankton-feeding fishes. A good staple diet will consist of a variety of frozen foods, such as enriched brine shrimp, Cyclops, Calanus copepods, smaller Mysis shrimp, krill, and small ova, such as oyster eggs and fish eggs. Many individuals will also accept water-logged bits of flake food, as long as the particles are small enough to ingest. They will rarely pick food off the bottom substrate or while it floats on the surface of the water. They prefer to feed on morsels that are swept about the tank by water currents, which more closely resembles their normal feeding behavior. They are naturally thin fish that don’t have lots of fat reserves. Therefore, it is important to get them feeding as soon as you can. Once they begin eating, feed them three times a day or more.

Although you should avoid purchasing specimens that look emaciated or that have a curvature to the back, the dart gobies are fairly disease and parasite resistant. I have seen a whole tank of marine fishes wiped out by disease—all that is except a group of Zebra Dartfish! On rare occasions, small gnathid isopods will attach to dartfish fins at night, but in most cases they will drop off when the lights are turned on. Cleaner wrasses (Labroides) and some neon gobies (Elacatinus) can be employed to pick smaller isopods off your fishes, and small predators that feed on motile invertebrates will eat these crustaceans when they are free-swimming. I have had dartfishes chaff against the sand on occasion, without any further signs of disease or parasitic infection ever manifesting itself. Be aware that these fishes will swim into the intake tube of canister filters, if the protective strainers are left off, and they will also plunge into overflow boxes. They are amazing jumpers, hurling themselves out of an open tank. In most cases, a jumping dartfish is unhappy dartfish; that is, it does not have suitable hiding places and/or is being harried by a tankmate. Dartfish lifespan in the aquarium is typically around five years.

Dartfish Species

Of the 21 described dartfish species, five are readily available to aquarists, and several others do show up sporadically. One of the more ubiquitous species is the very attractive Scissortail or Blackfin Dartfish, Ptereleotris evides (it also sold as the “Scissortail Goby”). It is distributed from the Red Sea to the Society Islands, north to the Ryukus and south to New South Wales, Australia, Lord Howe and Rapa Islands and attains a maximum length of 14 cm (5.5 in.). This species is most common on exposed outer reef slopes, but is occasionally encountered on protected reef flats, in lagoons and in sheltered bays. It occurs at depths from 2 to 15 m (7 to 50 ft.). As juveniles the Scissortail Dartfish forms small shoals, while adults most often occur in pairs. It is one of the more durable aquarium ptereleotrids, quickly adjusting to a passive community aquarium. It is best to keep this species in pairs, and it is usually tolerant of others in the genus as well. It is well-suited to either a shallow or deep water reef aquarium.

If P. evides is one of the most common dartfishes in the aquarium trade, the Lined Dartfish, Ptereleotris grammica, is one of the rarest. It is also one of the most expensive and most spectacular. The reason for its scarcity can be explained by its preference for deep water and the risks and expenses involved in its collection, but also by the fact that it is rarely seen by divers. (Ichthyologists who have spent hundreds of hours exploring the habitat where this fish resides, tell me they have only seen one or two individuals in a life time of diving.) Described by Dr. Jack Randall and Roger Lubbock in 1982, Ptereleotris grammica occurs from the Ryukus in Japan to the northern Great Barrier Reef. There is a very similar species off Mauritius, the Maldives and South Africa, that was once considered a subspecies of P. grammica, but it is now classified as distinct and is known as Ptereleotris melanotus.

The Lined Dartfish is found at depths of 35 to 60 m (114 to 195 ft.) on sand-rubble slopes, sometimes with mixed sponge and rubble patches—not on well-developed reefs. It is typically encountered singly or in pairs, but, on rare occasions, it may form loose groups.

Ptereleotris grammica, the Lined Dartfish, is a rarely encountered gem that is best left to more advanced aquarists. Image: Yi-Kai Tea.

When it comes to its husbandry, acclimation can be very tricky. In fact, I would recommend this species (and closely related forms mentioned later) to only the most advanced aquarists. The problem with this fish is that even by dartfish standards, it is very skittish. Because of its proclivity for cryptic living at greater depths, the best chance of success is to keep it in a dimly-lit aquarium and in an area with low traffic (this is not a fish suited to an aquarium in an office waiting room or a young child-rich environment). Any movement outside the aquarium will send this fish fleeing for cover. The other key to keeping this species is peaceful tankmates. Of course, this applies to most Ptereleotris spp., but even more so for P. grammica because of its amplified timidity. If placed in a typical reef aquarium, with a frenetic mix of tangs, fairy wrasses and anthias, it is likely to never be seen again or only during brief, rapid forays to snatch pieces of food as they float past. That is not saying fish tankmates are not a good idea. Dither fishes can create a sense of security for your Lined Dartfish, eliciting increased boldness and a possible feeding response. Once brazen enough to leave its shelter, it should accept most common dartfish fare. In some cases, live food may be required to induce more finicky individuals. Keep one or a pair of these fish together—keeping them in groups is more risky than others in the genus, as they have been known to nip each other (possibly intrasexual aggression?). It reaches a length of 10 cm (3.9 in.) and is best housed in a tank of at least 75 gallons with lots of open sand bed and rubble mounds.

I cannot leave this discussion on P. grammica without mentioning a couple of closely related forms. One of the most spectacular of these is Ptereleotris kallista, the Beautiful Dartfish. The only known individuals of this gorgeous species were collected off the Philippines by aquarium fishers. Like P. grammica, it has a high first dorsal fin (about twice the height of the second dorsal), with long spines that form filaments. The Bandtail Dartfish (Ptereleotris uroditaenia) also has the sail-like first dorsal fin and is a deep sand/rubble slope resident. It is known from Brunei, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and Australia. The aquarium husbandry of these two species is likely similar to their close cousin, P. grammica.

Another unique and beautiful ptereleotrid is the Filamented or Threadfin Dartfish (Ptereleotris hanae). Its color can vary from metallic green to bright blue, often with a darker blue area on the lower part of the body. This species attains a maximum length of around 12 cm (4.7 in.)—that does not include the trailing caudal filaments which can be as long as two-thirds of the standard length—and it is distributed from the Philippines to Line Islands, north to southern Japan and south to northwestern and New South Wales, Australia. It occurs over rubble and sand bottoms adjacent to reefs, at depths from 3 to 50 m (7 to 163 ft.). In New South Wales, Australia, it is observed in estuaries. Juveniles form aggregations, while adults are usually in pairs, with adult pairs sometimes occupying burrows in close proximity to one another and forming larger colonies. The Filamented Dartfish lives under coral rubble as well as in the burrows of pistol shrimp and their shrimp goby associates. Large males perform a flashy display when showing off to females or rival males. During these displays, they fully extend their pelvic fins, erect all of their median fins and their color intensifies. This dartfish is not uncommon in the trade and is moderately hardy. It was once commonly misidentified as P. rubristigma in aquarium circles, but that species is easily distinguished by the red spot at the base of the pectoral fin. A fascinating display for those who are intrigued by symbiosis may include an Amblyeleotris shrimp goby, its pistol shrimp associate, and a pair of Threadfin Dartfish.

Helen’s Dartfish (Ptereleotris helenae) and the Florida or Blackmargin Dartfish (P. calliura) are two of three species known from the Tropical Eastern Atlantic. The former occurs from Georgia to Southern Florida, the Bahamas, and the Caribbean, while P. calliura is known from North Carolina Bank Reefs to southern Florida, as well as the Eastern Gulf of Mexico. Helen’s Dartfish tends to be pearly white overall, with purple, blue and or rose highlights, while the Florida Dartfish has a black dorsal fin margin and pointed caudal fin (it is rounded in P. helenae). These dartfishes behave much the same as their Indo-Pacific relatives, being most often found over sand or sand and mixed rubble slopes—the same habitat often preferred by the Yellowhead Jawfish (Opistognathus aurifrons), hovering, with the head slightly down, waiting for passing planktors to drift past. They are both monogamous, but numerous pairs may be found in relatively close proximity to one another. Juveniles often live among the adults. Thresher (1980) noted that the Atlantic Ptereleotris live in U-shaped burrows, but is not clear if these are built by infaunal creatures (perhaps inn-keeper worms) or by the dartfishes themselves. Colin (1973) describes their burrows as being narrow and reaching “considerable depth” and notes he has never seen them construct the burrow. When it comes to Atlantic dartfish species in the aquarium hobby, I have found the P. calliura to be much more common in the hobby than P. helenae. However, the husbandry requirements of both species are similar to other ptereleotrids. They will often hide for a week or more when first introduced, so be patient with them and be very selective when it comes to their piscine neighbors. A fascinating biotope tank might contain a couple pair of these fish and one or more Yellowhead Jawfish—just be sure there are enough hiding places to go around. Another good selection for the Atlantic dartfish aquarium is a group of adult Masked Gobies (Coryphopterus personatus). Rubble patches on the sand bed will provide refuge for these diminutive, hovering gobies, as well as their dartfish tankmates.

The Spottail or Blue Dartfish (Ptereleotris heteroptera) is commonly available in North American fish stores. This lovely species is an intense blue overall, with a black spot on its caudal fin, making it a popular choice for many aquarists. In some locations, this dartfish has a bright yellow tail. It reaches a maximum length of about 12 cm (4.7 in.) and is distributed from the Red Sea east to the Hawaiian, Marquesas and Society Islands, north to the Ryukus and south to New South Wales, Australia and Lord Howe Islands. The Spottail Dartfish lives over sand and rubble bottoms, in sheltered bays, lagoons, on reef flats and seaward reef slopes. It occurs at depths from 7 to 46 m (23 to 150 ft.) but is most common between 15 to 35 m (50 to 116 ft.). As juveniles, Spottail Dartfish are gregarious, living in small to large aggregations, but adults are often found in pairs. It refuges in holes in the sand, sometimes with pistol shrimp and shrimp gobies, or among coral rubble. This dartfish will swim up to 2 m (7 ft.) into the water column to catch its zooplankton prey. Although beautiful, it is one of the shyest members of the genus. Because it is sensitive to any movement outside of the tank, if you startle it, the fish will often dart into a hiding place or attempt to catapult itself from the aquarium (sometimes ricocheting off the aquarium top back into the tank). One way to help this fish overcome its shyness is to keep it with more fearless ptereleotrids, like the Green Dartfish (P. microlepis), or other dither fishes.

The Green or Smallscale Dartfish (Ptereleotris microlepis), which is often referred to by aquarists as the “Green Gudgeon Goby,” is one of the best species for the home aquarium. This species, which is metallic green or bluish gray overall with blue lines on its face, reaches a maximum length of 12 cm (4.7 in.) and is distributed from the Red Sea east to the Line and Tuamotu Islands, north to the Ryukus and south to New South Wales, Australia. The Green Dartfish lives over sand and rubble substrate, usually in turbid lagoons and near coastal reefs, at depths between 1 to 22 m (3 to 72 ft.). Juveniles of this species are almost always found in aggregations, while adults occur singly, in pairs, groups, or even true polarized schools. For example, in the lagoon at Enewetak, groups consisting of 3 to 150 individuals are commonly observed. Smaller groups, which often contain fewer than nine individuals, are usually observed hanging from 5 to 15 cm (2 to 6 in.) over the entrance of a burrow. Larger schools, which are usually comprised of 60 individuals or more, roam over large areas and will often ascend up to 2 m (7 ft.) over the bottom. In certain areas, it is not uncommon for the Green Dartfish to occupy burrows with Orangespotted (Valenciennea puellaris), Sixspot (V. sexguttatus) and Goldenheaded Sleeper Gobies (V. strigata). The Green Dartfish is one of the most durable and boldest members of this genus. It is best to keep this species in groups numbering from 3 to 20, depending on the size of the aquarium. Large shoals make a very impressive display! It should also be provided with plenty of places in which to hide if it feels threatened.

Full article with additional species images can be found in CORAL, September/October 2020.

The Monofin Dartfish or Monocle Dartfish (Ptereleotris monoptera) is a bolder member of the genus. This species, which can attain a maximum length of about 12 cm (4.7 in.), is recognized by the black bar under its eye and its continuous dorsal fin. It ranges from Indonesia to New Guinea, north to southern Japan and south to the Great Barrier Reef. The Monofin Dartfish is most common in on fore reef drop-offs, often in clear water at depths from 3 to 50 m (10 to 165 ft.) and forms small to large loose groups, often joining with aggregations of other Ptereleotris spp. It readily adjust to life in peaceful aquarium and is a fairly bold, spending much of its time in the open. It should be kept in pairs, small conspecific groups, or with other dartfishes, in a shallow or deep water reef aquarium. It is not a difficult dartfish to keep.

The Redspot Dartfish (Ptereleotris rubristigma) was only recently described but has been showing up in the trade for many decades. In fact, this rather common aquarium dartfish was often misidentified as P. hanae. That said, it is easy to differentiate from others in the genus by a red spot at the base of the pectoral fin on each side. Also, the second dorsal spine is filamentous, adding to the fish’s appeal. This species, which is known from Indonesia, reaches a maximum length of 10.5 cm (4.1 in.) and is a resident of sand and rubble slopes bordering reefs. It is found at a depth range of 15 to 60 m (49 to 195 ft.) and is found singly and in pairs. As well as being one of the most attractive members of the genus, this is one of the hardiest dartfishes, in my experience. Although not quite as bold as the Green Dartfish, it is one of the more “fearless” of the Ptereleotris.

The Zebra Dartfish or Bar Goby (Ptereleotris zebra) is the most popular member of this genus in the aquarium trade. This is, in part, because of its pleasing color pattern which consists of a greenish gray body with numerous orange to pink vertical bars or stripes that are edged with blue. It has a prominent fleshy barbel on its chin. Like its relatives, it is also peace-loving and inexpensive. This species attains a maximum length of just over 11.5 cm (4.5 in.) and is distributed from the Red Sea east to the Line and Marquesas Islands, north to the Ryukus and south to the southern Great Barrier Reef. The Zebra Dartfish has unique habitat preferences. It is found on exposed seaward reefs, at depth from 2 to 30 m (7 to 98 ft.); however, it is most common at depths between 2 to 4 m (7 to 13 ft.). This fish usually lives in aggregations over hard, gently sloping, surge-prone, current-swept bottoms. It is an attractive and interesting aquarium inhabitant, but one that should be housed with less aggressive fish species. It needs to be provided with numerous hide places and “appreciates” turbulent water conditions. The Zebra Dartfish acclimates more readily if kept in small groups. Green Dartfish, which are often bolder initially, can be a good dither species to keep with P. zebra. This species often spends very little time in the open for the first several days, and as long as two weeks, after it is introduced to its new aquarium home. However, once fully acclimated, it will spend most of its time in the open. During courtship, and when attempting to drive away rivals, males perform lateral displays, where they erect their median fins, extend their pelvic fins and their chin barbel and their color intensifies (especially the black area under the eye). When courting, the male will dash underneath a female and nudge her flank with his snout. The pair will then engage in parallel swimming, where the two fish will swim alongside one another. The eggs, which are gray, are laid in the burrow or in a cave and tended by the female.

That ends our survey of this amazing group of goby-like fishes that are almost perfect for the coral reef aquarium. If you haven’t considered “playing with” darts in the past in your peaceful marine community tank, I hope this will inspire you to do so. Happy fishwatching!

Author

Author Scott W. Michael.

Scott W. Michael is an internationally recognized writer, underwater photographer, and marine biology researcher specializing in reef fishes. A marine aquarist since boyhood, he has kept tropical fishes for more than 30 years, with many years of involvement in the aquarium world, including a period of tropical fish store management and ownership.

He is the author of a number of bestselling marine aquarium books, including the Reef Fishes Series, PocketExpert Guides to Marine Fishes, Reef Aquarium Fishes, Adventurous Aquarist Guides to Saltwater Fishes, Marine Invertebrates and Nano-Reef Species. Scott Michael lives with his wife, underwater photographer Janine Cairns-Michael, in Lincoln, Nebraska.

References

Allen, G.R. and Erdmann, M.V., 2012. Reef Fishes of the East Indies: volumes I–III, Tropical Reef Research. Perth, Australia, 1, p.3.

Colin, P.L. 1973. Burrowing behavior of the Yellowhead Jawfish, Opistognathus aurifrons. Copeia, 1973:84–89.

Debelius, H. and H. A. Baensch. 1994. Marine Atlas. Mergus-Verlag Gmbh, Melle, Germany, 1215pp.

Kuiter, R. H. 1993. Coastal Fishes of South-Eastern Australia. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 437pp.

Paulson, A. C. 1978. On the commensal habits of Ptereleotris, Acanthurus, Zebrasoma with fossorial Valenciennea and Amblygobius. Copeia, 1978:168–169.

Myers, R.F. 1989. Micronesian Reef Fishes. Coral Graphics, Guam, Pp. 228.

Thresher, R.E. 1980. Reef fish; Behavior and Ecology on the Reef and in the Aquarium. Palmetto Publ. Co. St. Petersburg, FL. 171 pp.to the Great Barrier Reef.

Print Edition

The archival print version of this this article appears in CORAL Magazine, September/October 2020, Volume 17.5.

Copies available at: Coral Magazine Back Issues