Soft plastics: what has happened and where are we up to now?

Soft plastics are the fastest-growing plastic packaging category and are almost always single-use . They’re embedded in the Australian conscience – we use them daily and we no longer like the idea that they will inevitably end up in landfill.

According to research by the Minderoo Foundation, Australians generate more single-use plastic waste per capita than any other country in the world – about 60 kilograms a year. According to the government’s National Plastics Plan, Australia goes through 70 billion pieces of soft plastics each and every year – that's almost 3000 pieces per person.

The collapse of RedCycle in November 2022 was a shock revelation for many Australians who had been diligently separating their soft plastics to return to their local supermarket for collection. The abrupt halt to the scheme left many Australians bitterly disappointed, even though the Australian Packaging Covenant Organisation estimated that less than five per cent of consumer soft plastic was collected by the REDcycle program.

But the RedCycle collapse may have had some positive impact on the future of recycling, as it shed spotlight on gaps and current failures in the industry. Although often portrayed in the media as the “bad guys”, RedCycle’s intention – to recycle post-consumer soft plastic packaging – was legitimate, but current recycling systems and a stunted buying market for recycled plastic goods meant that the supply of post-consumer plastics far outweighed processing capacity.

This resulted in tonnes of soft plastics being stockpiled in warehouses. Soft plastics are notoriously difficult to recycle, due to food contamination and because they’re made of different types of plastic which aren’t easily processed. But with industry and market development, it is doable.

Post-RedCycle, a Soft Plastics Taskforce was established between the three major supermarkets Coles, Woolworths and Aldi, with the aim of launching a new supermarket soft plastic collection scheme. That collaboration has resulted in an interim return-to-store collection program to be re-introduced from late 2023, with the real goal in sight an industry-led National Plastics Recycling Scheme (NPRS) slated to be the future of soft plastic packaging recycling in Australia.

The NPRS has been developed by the Australian Food and Grocery Council, with funding support from the federal government and leading food and grocery manufacturers. The scheme transitions to a kerbside model of soft plastics collection, where household consumers place their soft plastics in a specific bag in their yellow recycling bin.

As an industry-backed scheme, food and grocery manufacturers who are members of the AFGC – including big wigs like Nestle, Kellogg’s, Haribo and Mars – pay a levy to support the cost of plastic collection and administration of the program. Bags of soft plastics will be extracted from the recycling system, sorted, cleaned, and shredded, before being sent to advanced recycling facilities where they are broken down into a crude type of oil – the same oil that plastic is made from in the first place. That “plasticrude” oil is then ready to be made back into clean, food-grade plastic packaging.

The NPRS scheme is currently in its pilot phase, with limited trials of kerbside collection currently being carried out in six Local Government Areas across Victoria, New South Wales and South Australia.

The NPRS has rightly been met with a lot of scrutiny. On World Environment Day, Gayle Sloan, CEO of Waste Management and Resource Recovery Association Australia, questioned the viability of the NPRS, saying that it fails to address “the full lifecycle of plastics”. Sloan pointed out that the scheme fails to establish national infrastructure for reprocessing soft plastics. Nor does it address “the most difficult and challenging part of the system, namely the creation of demand and end markets for the Australian collected material,” Sloan said.

She went on to call on the federal government to establish a standardised national system, which is an EPR Scheme – an extended producer responsibility scheme, which, in the definitive words of the Department of Climate Change, Energy the Environment and Water, places primary responsibility on the producer, importer and sometimes seller of the product to manage the end-life of the packaging.

But AFGC say that the NPRS is an EPR, since grocery and food manufacturers will pay the levy that funds the recycling system.

Recently, in a win for Australian recycling, federal and state government environment Ministers came together and agreed for the first time to impose mandatory packaging rules on manufacturers and retailers. This will include mandating obligations on packaging design and recycled content, as well as regulating harmful chemicals in packaging. It was also agreed that a national roadmap will be developed for staged improvements to the harmonisation of kerbside collections. For the NPRS, the news is fantastic, as mandating recycled material content in packaging begins the process of expanding a recycled plastics market.

It remains to be seen whether federal funding will continue incrementally, to allow for a full expansion of the NPRS program, including the establishment of new recycling facilities which can process soft plastics at national scale. In the meantime, some Councils like Randwick are accepting soft plastics for recycling – for their constituents only, while Curby is leading the way on the Central Coast.

Soft plastics should be collected in-store from late 2023, with the NPRS slated to begin operations nationwide in late 2024.

So what can we do now?

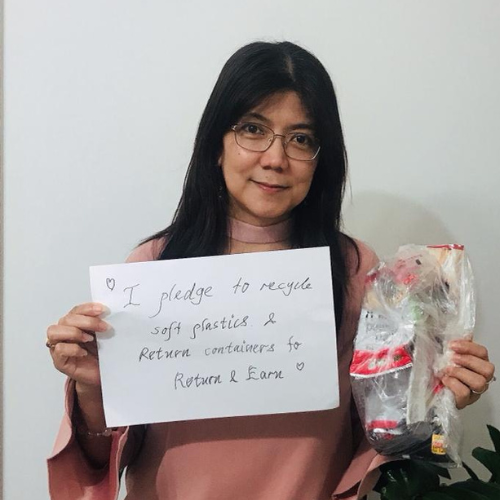

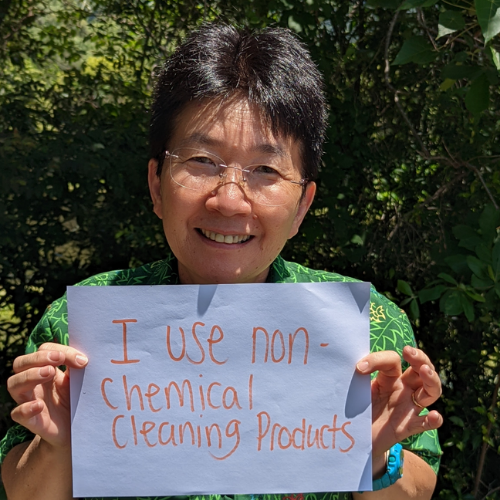

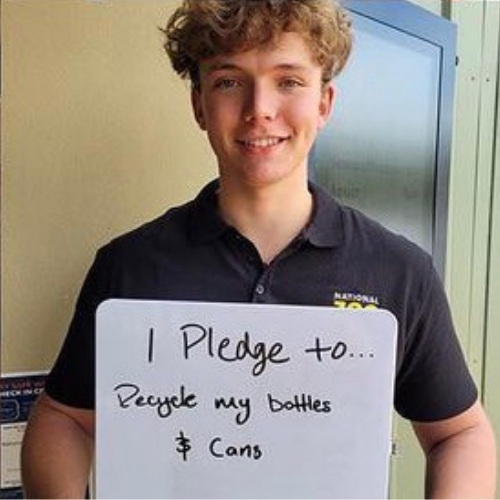

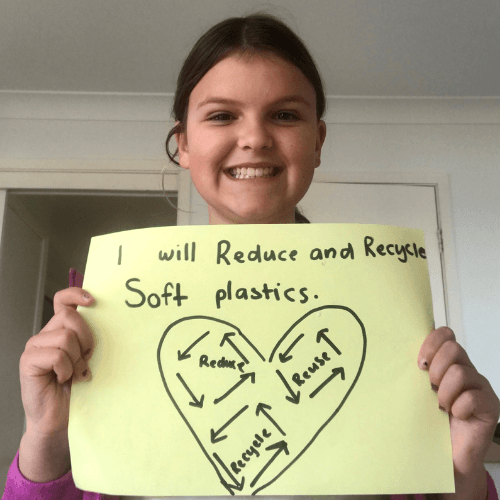

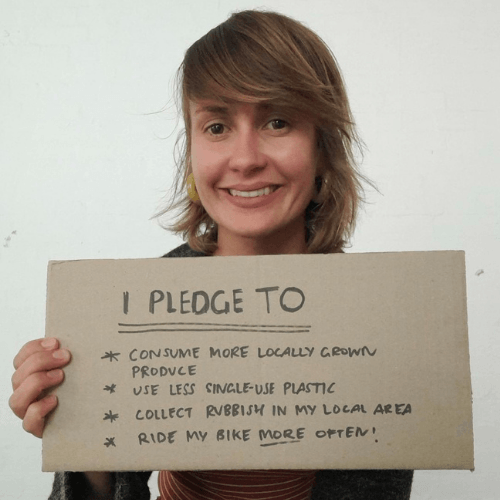

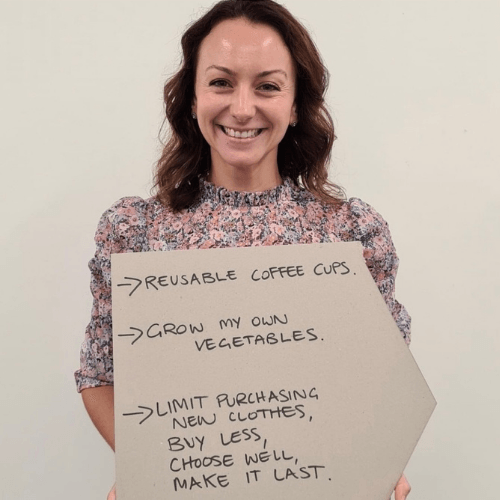

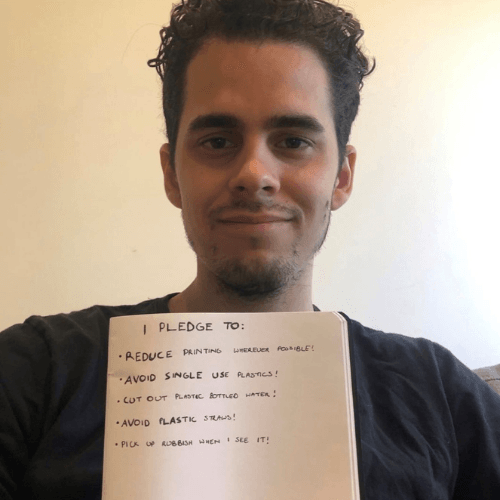

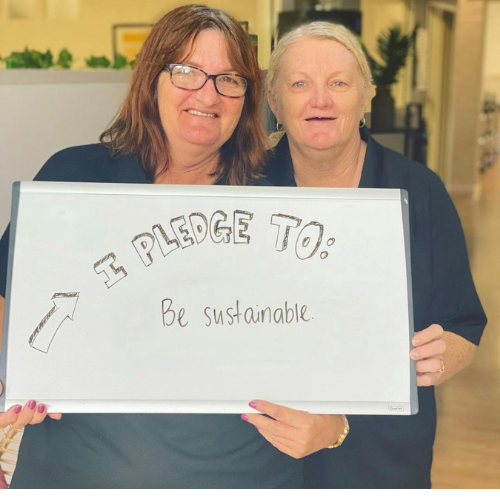

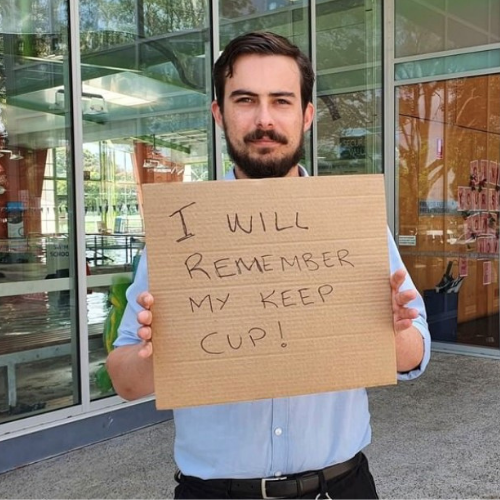

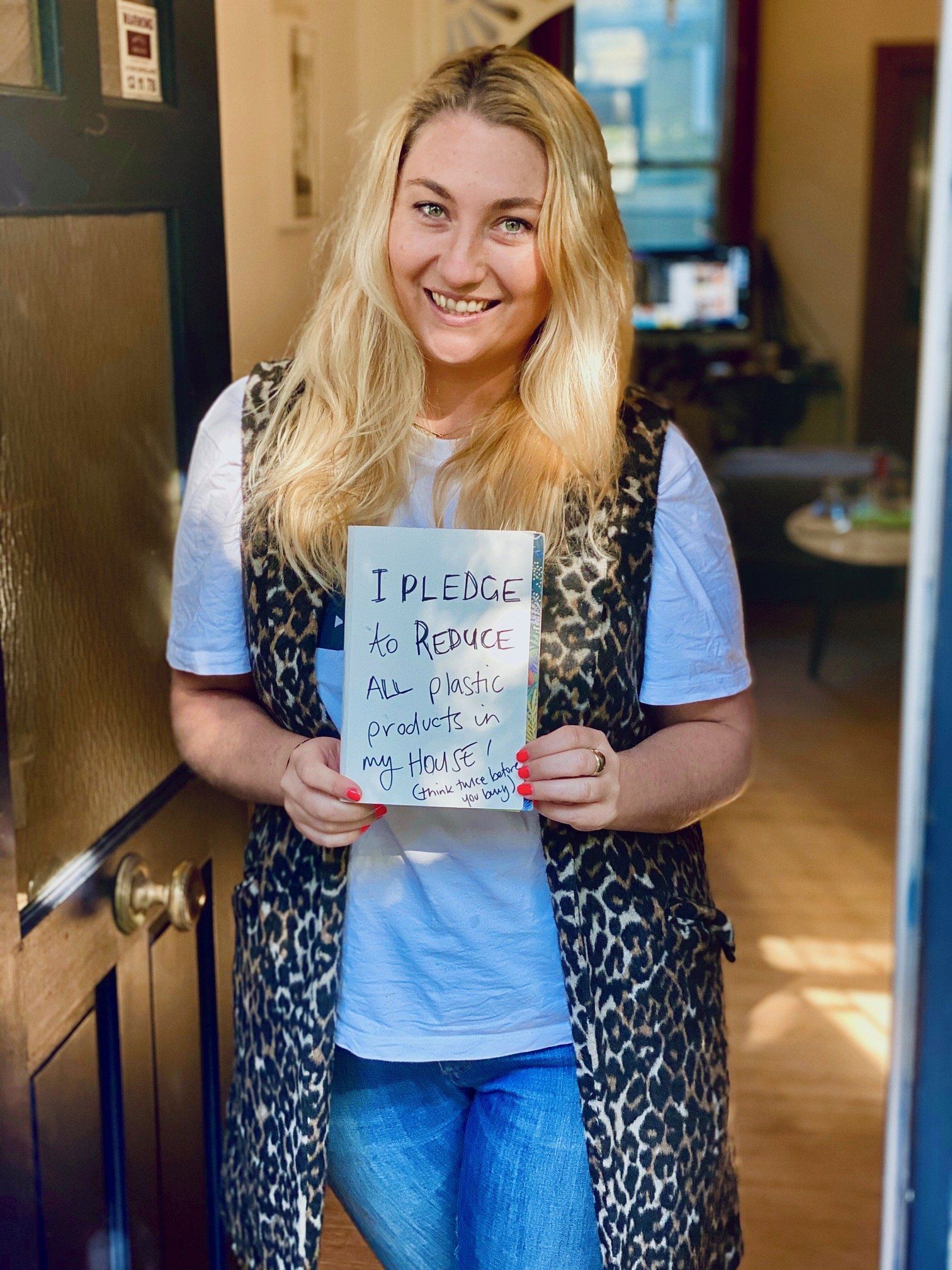

As consumers we can exert a lot of influence by our purchasing decisions. Recycling must become "the last line of thinking" in tackling plastic waste; it can’t be considered a magic bullet solution. The primary thought process should be: how can I avoid this in the first place. We need to get in the habit of expanding how we refuse, reduce and reuse, before we consider recycling.

We must make conscious choices and look at how we can cut down on any unnecessary plastics by thinking carefully about our purchases and the volume of plastic waste that we’re producing.

By Lucia Moon

Search for other blog topics:

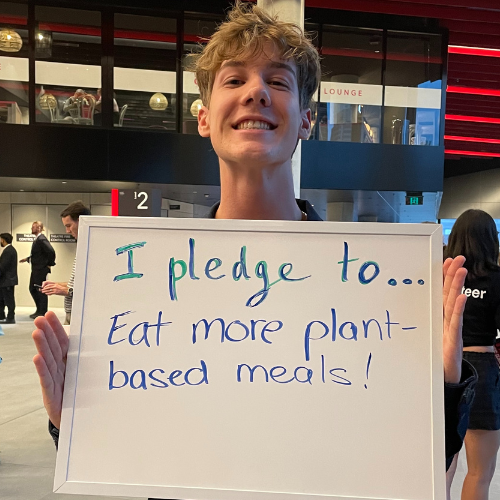

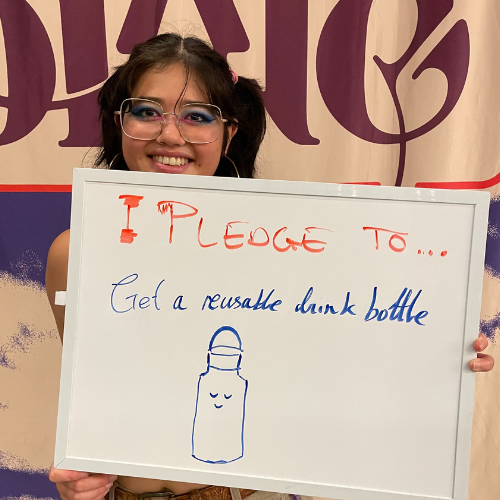

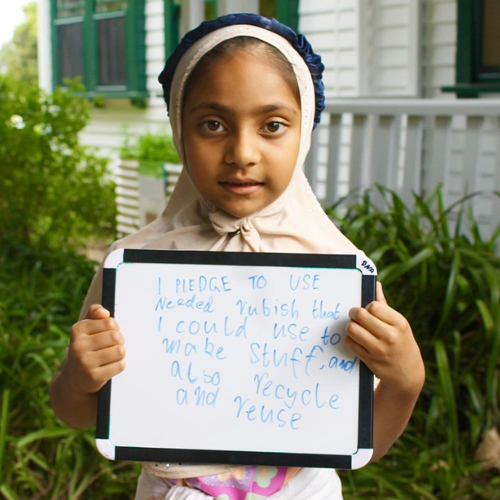

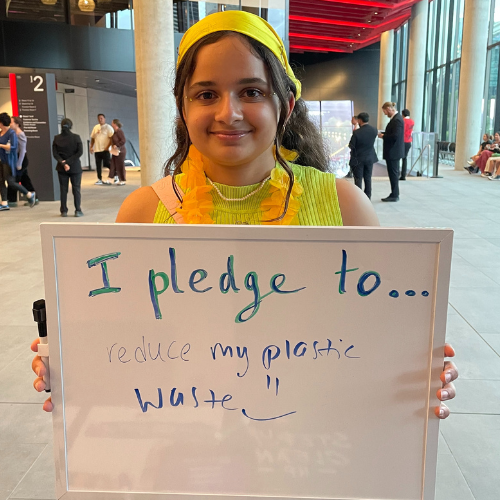

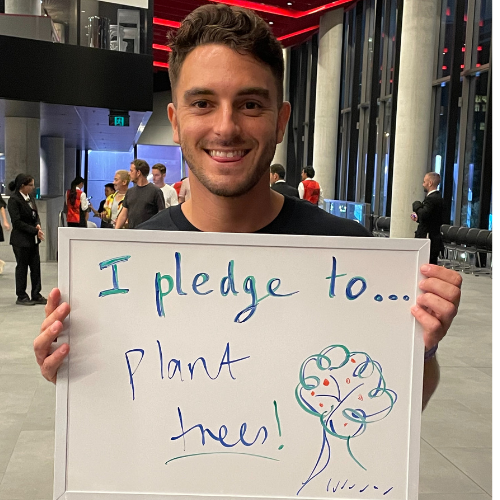

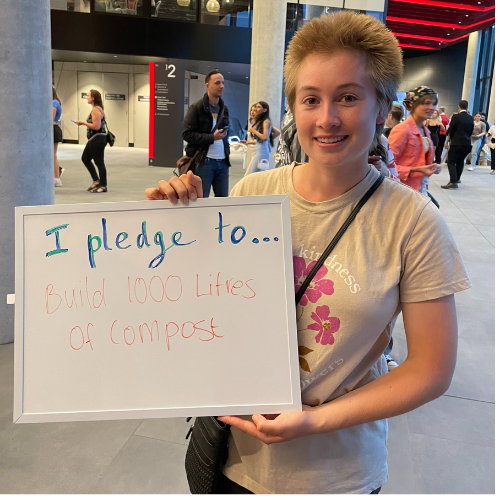

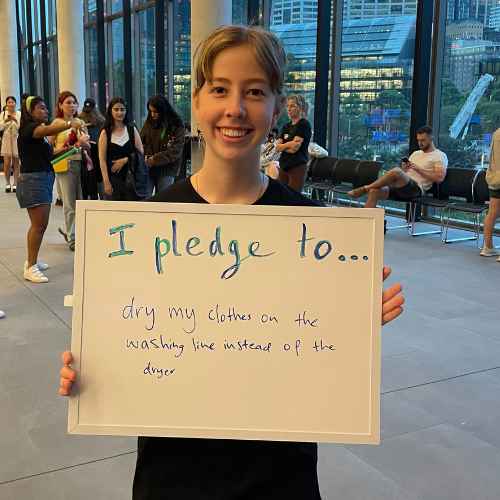

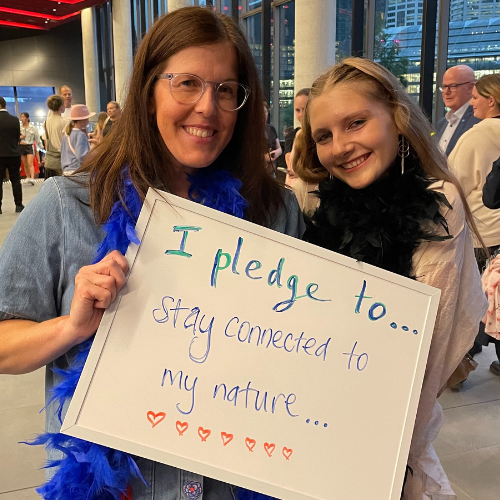

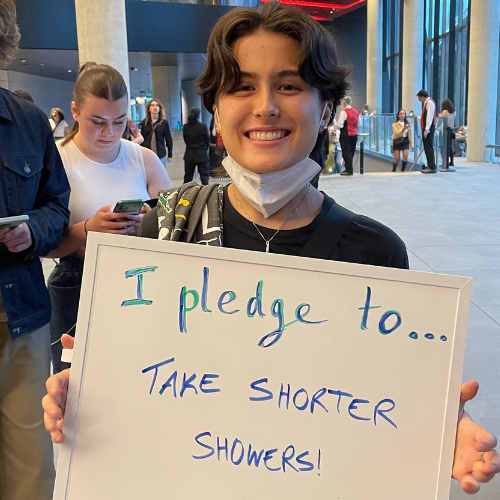

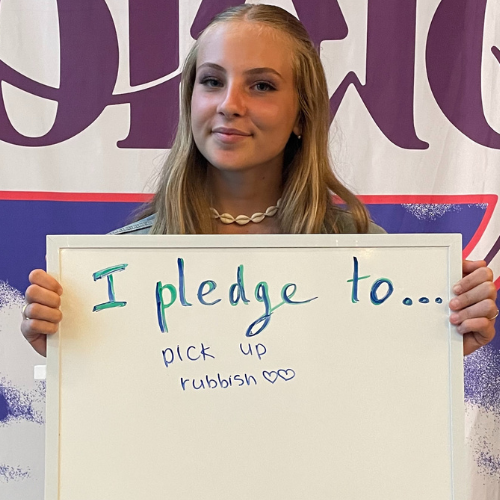

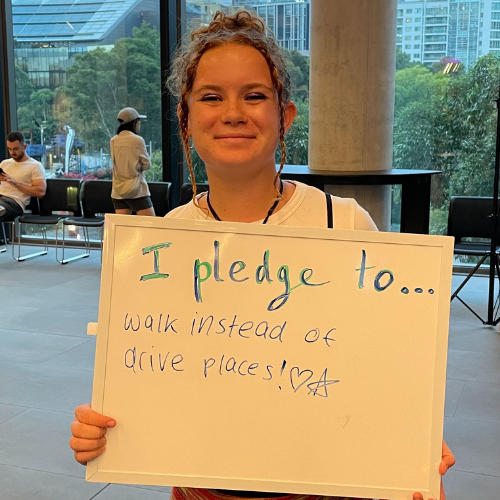

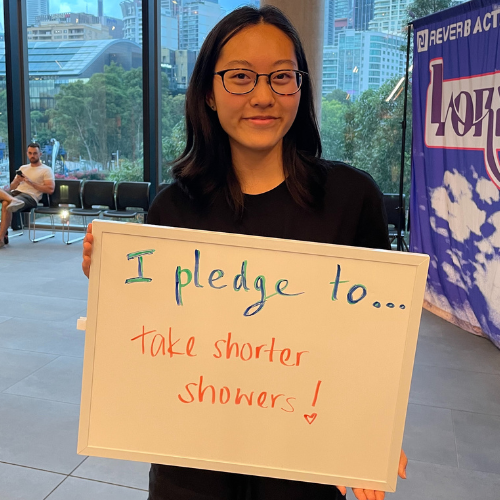

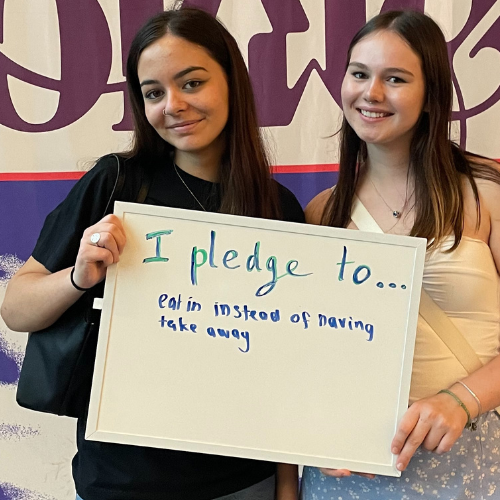

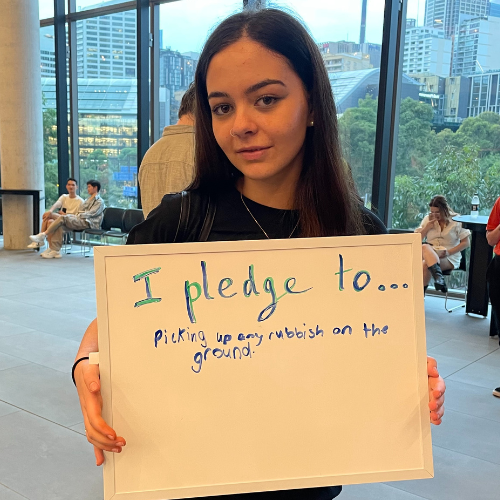

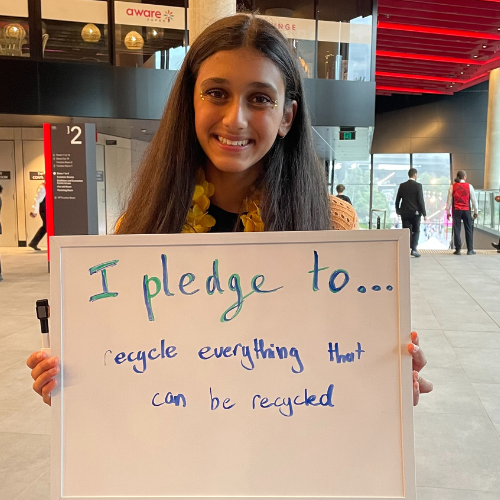

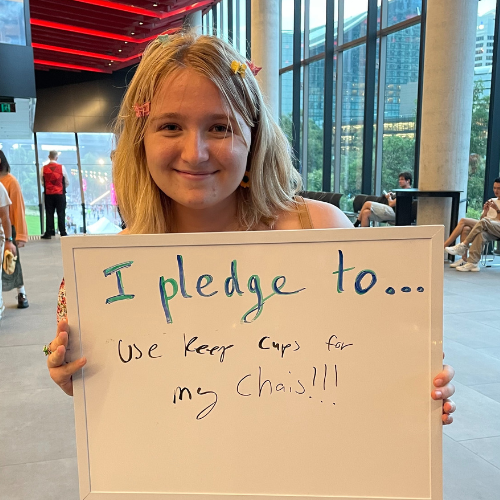

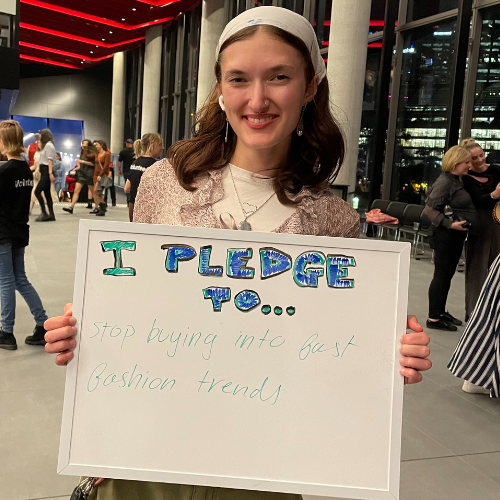

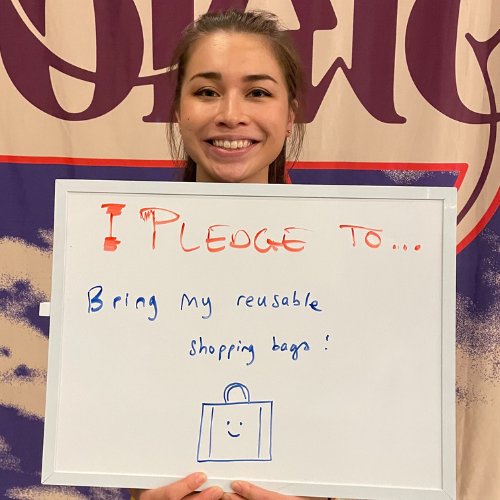

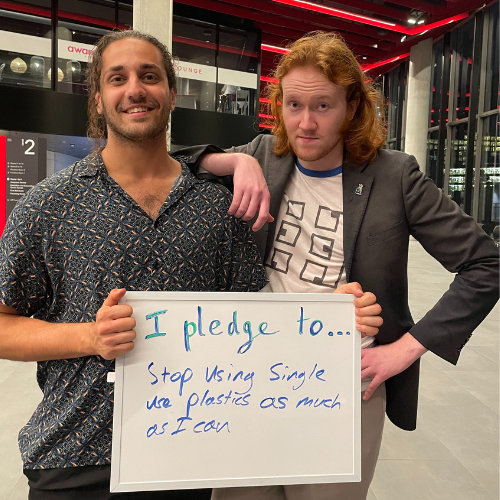

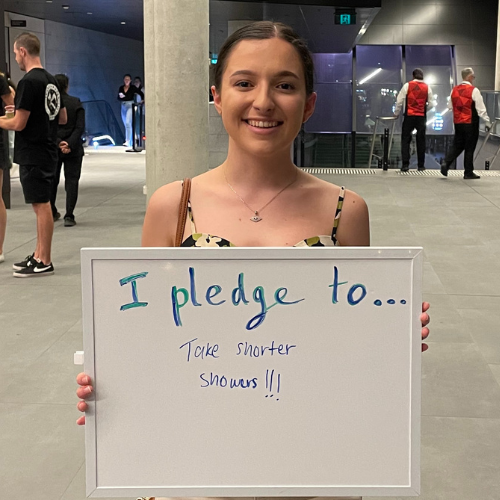

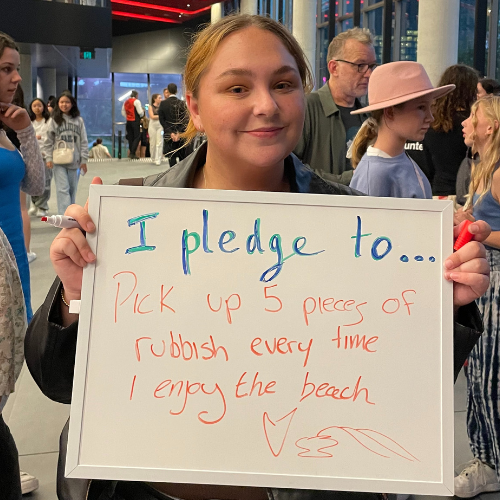

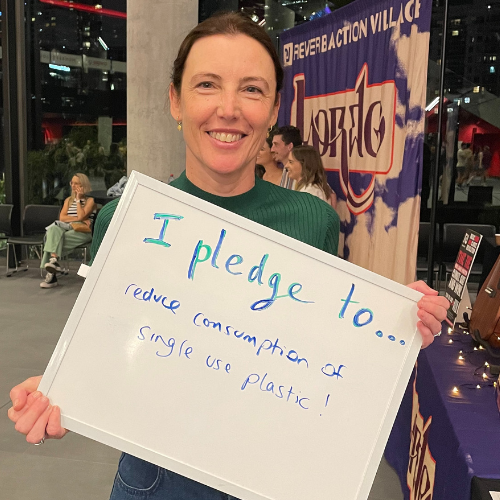

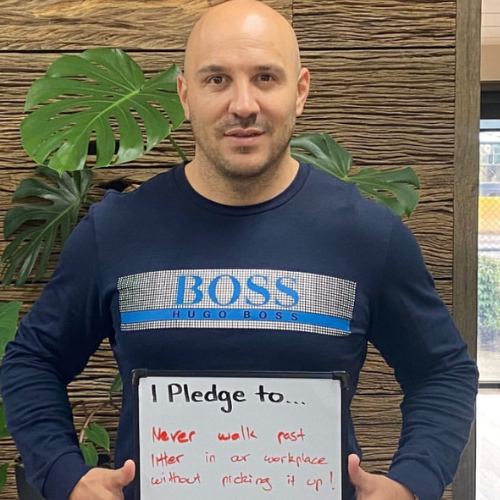

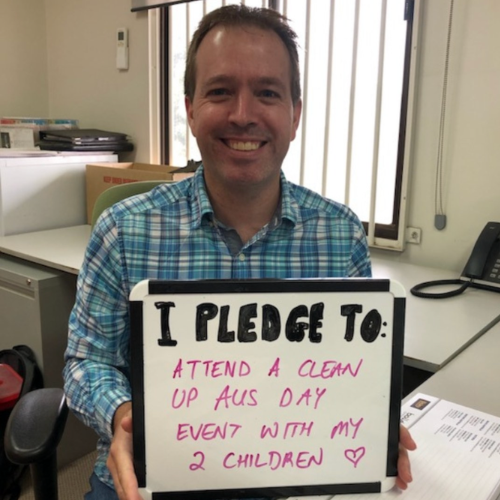

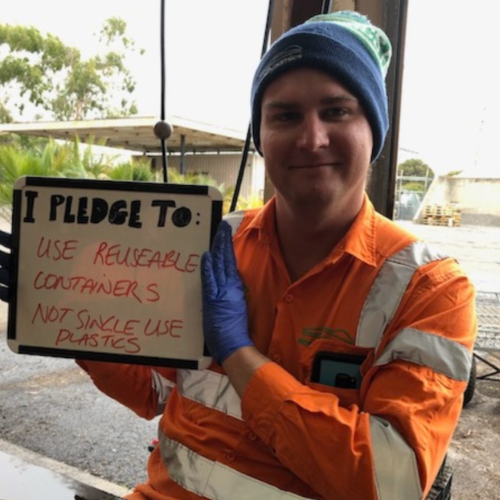

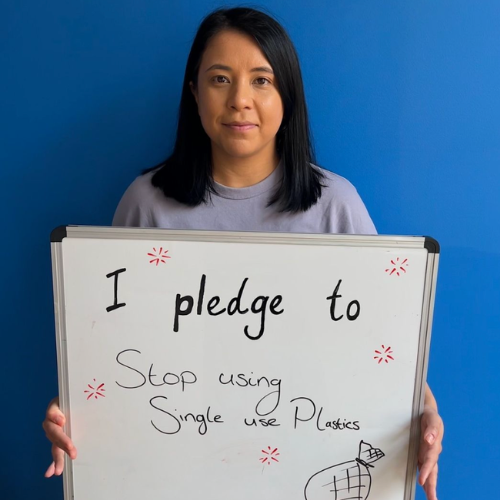

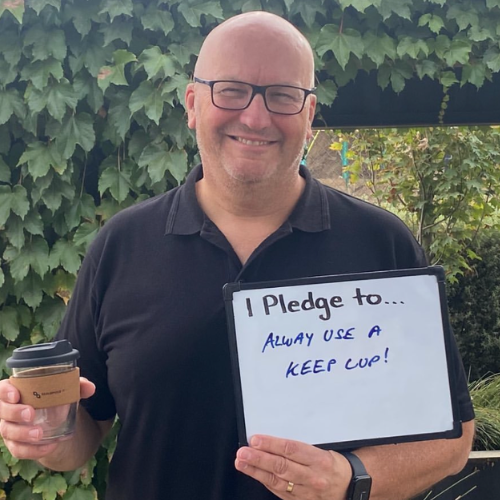

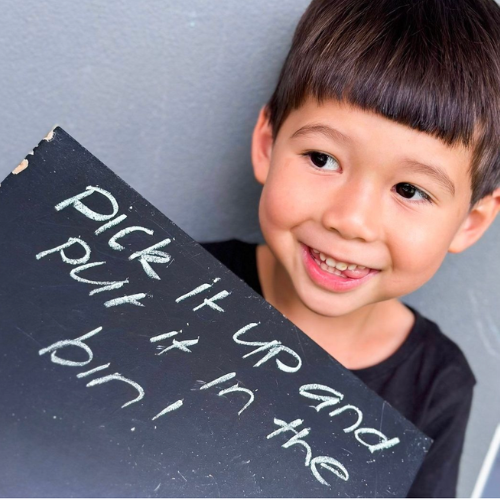

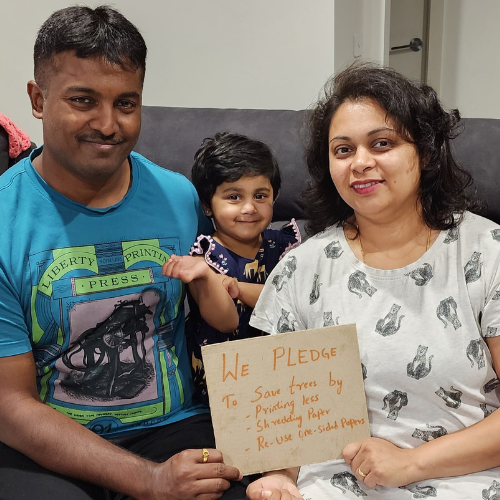

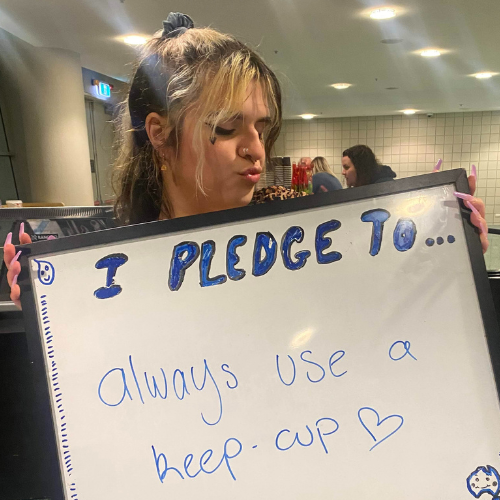

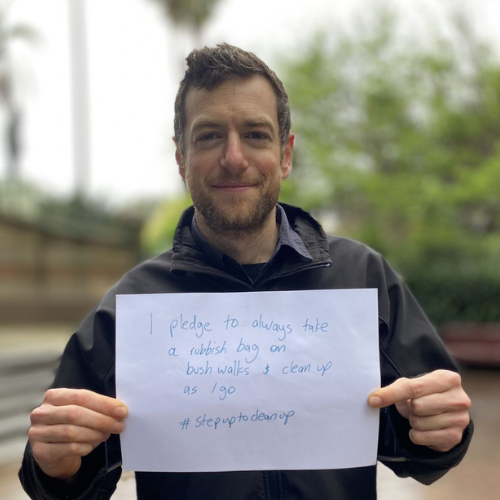

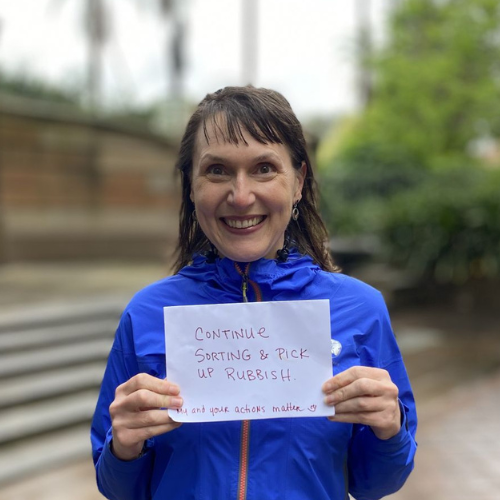

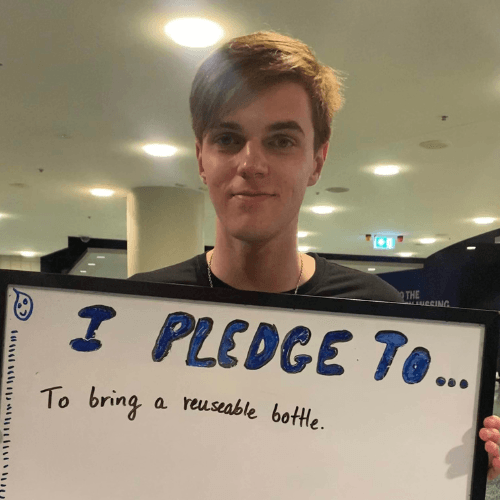

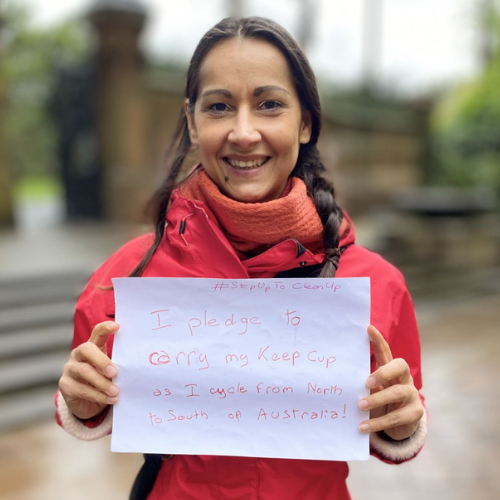

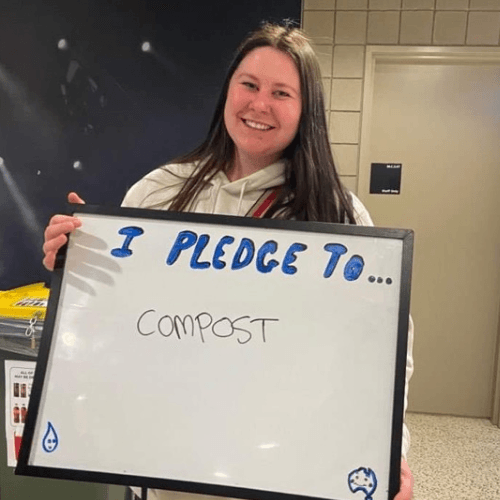

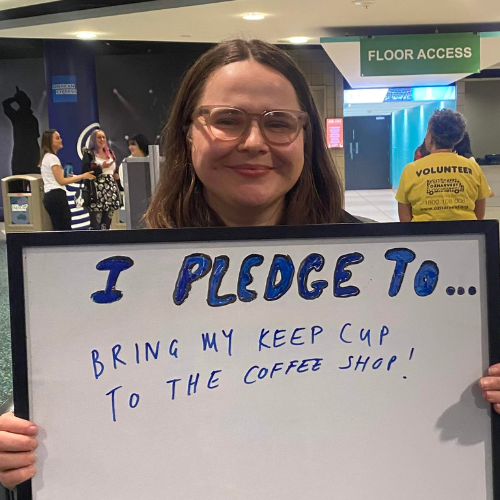

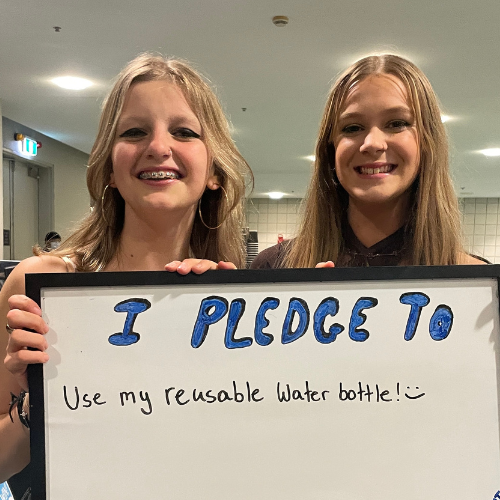

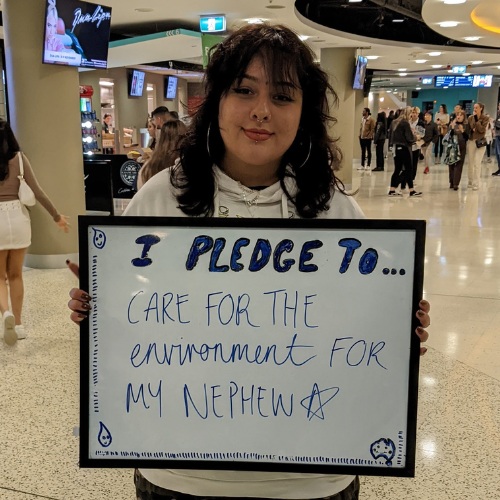

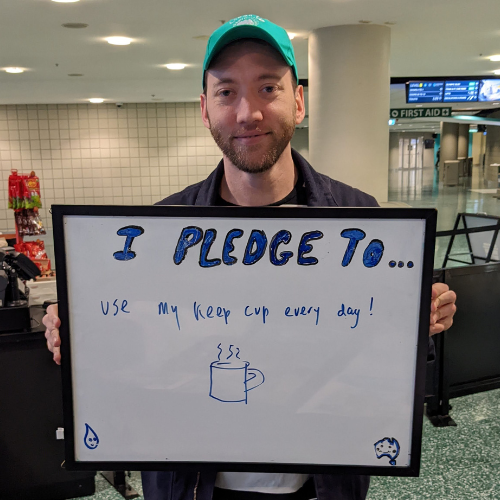

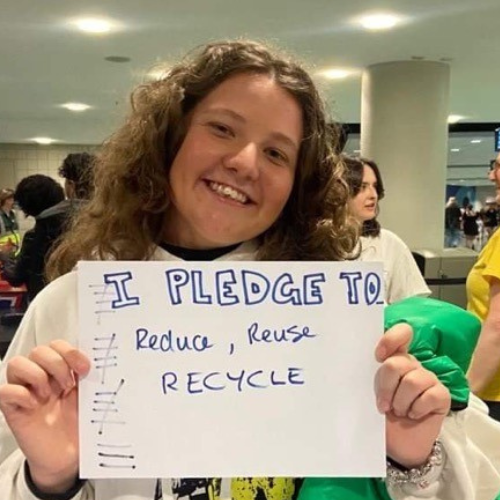

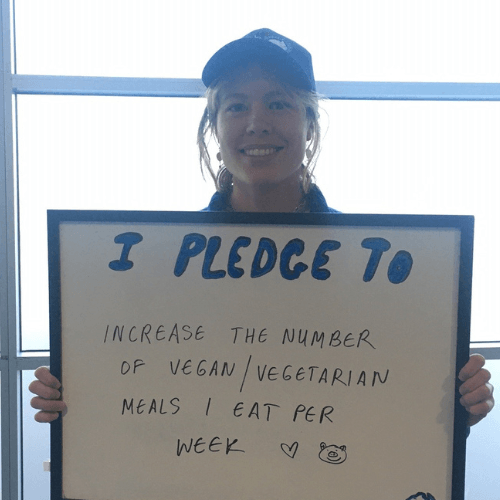

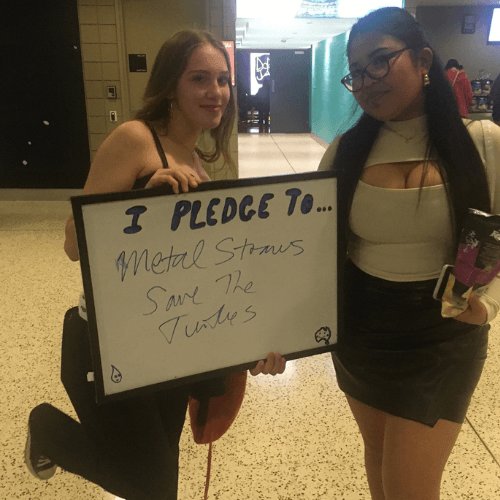

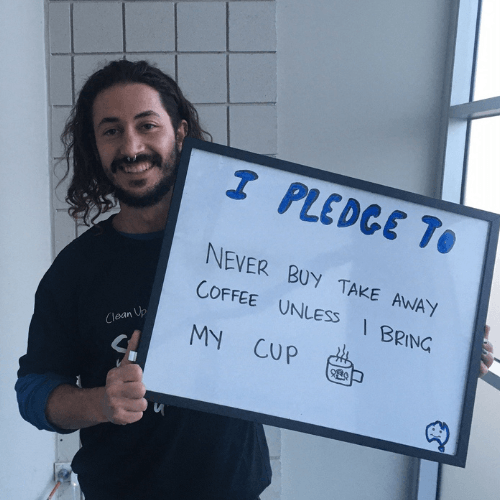

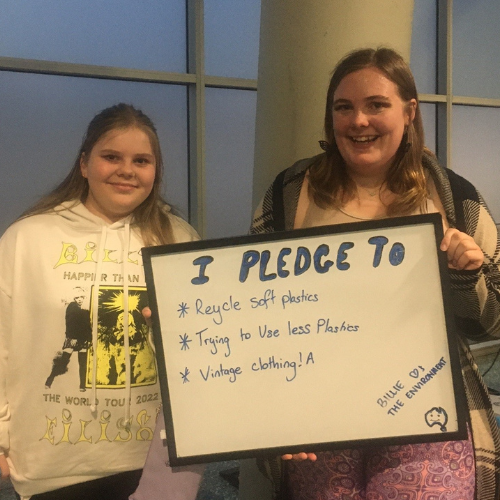

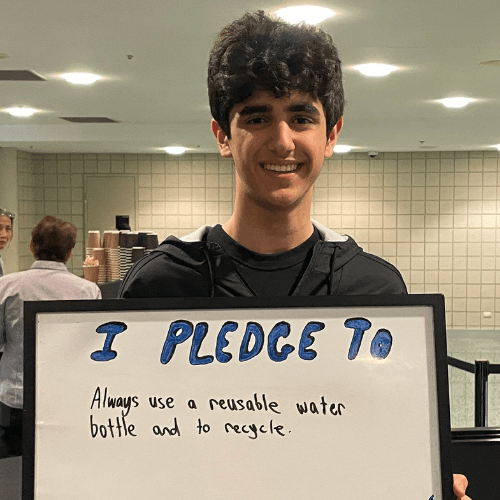

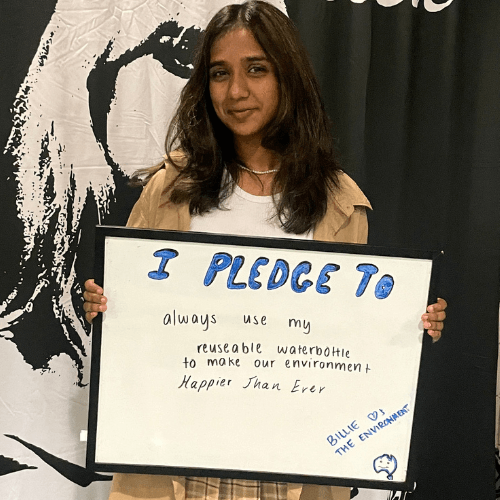

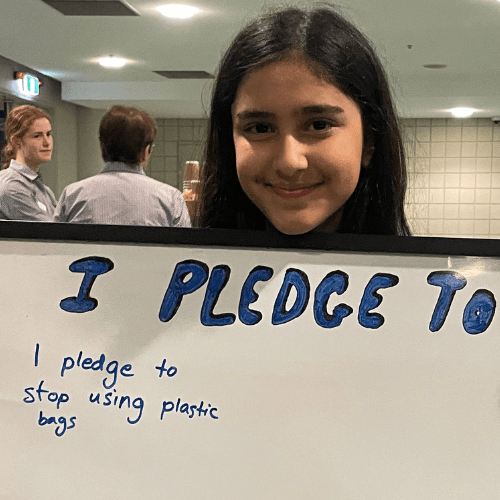

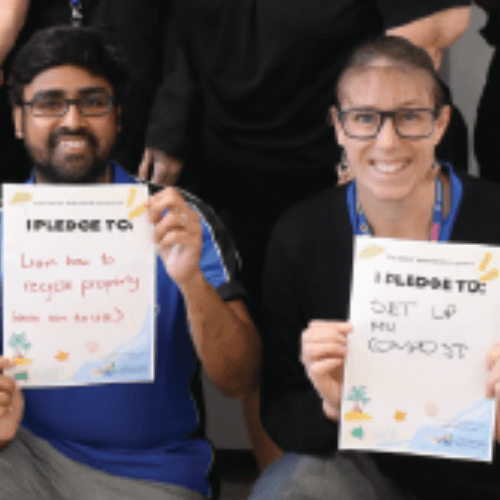

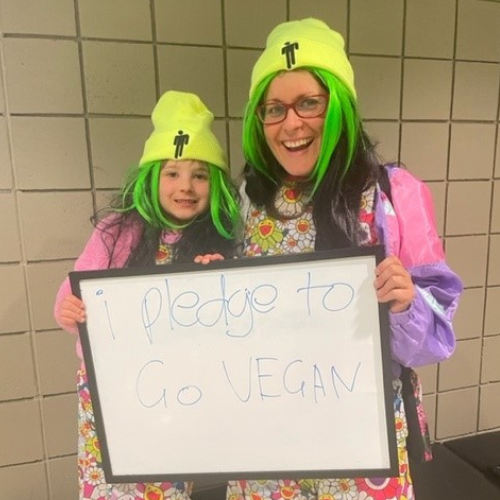

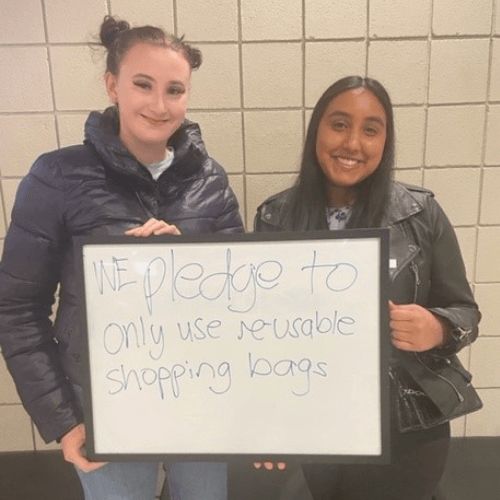

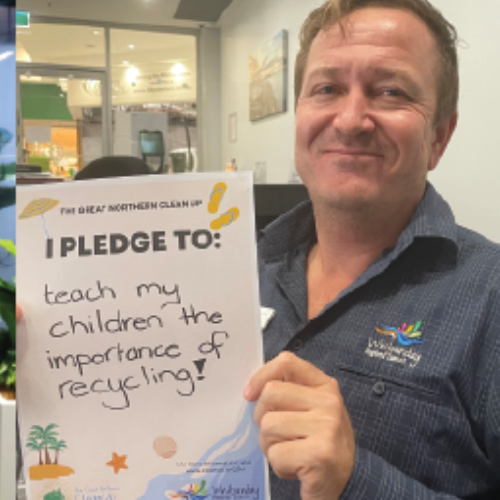

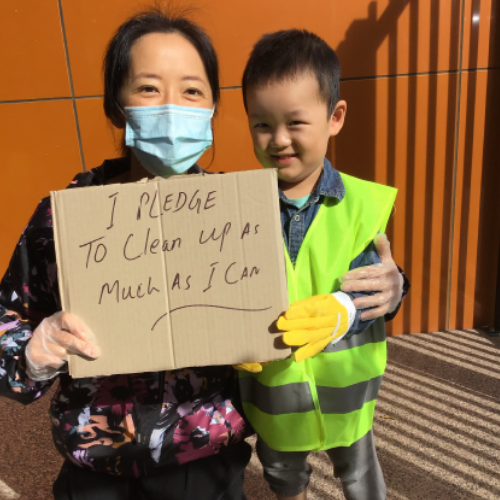

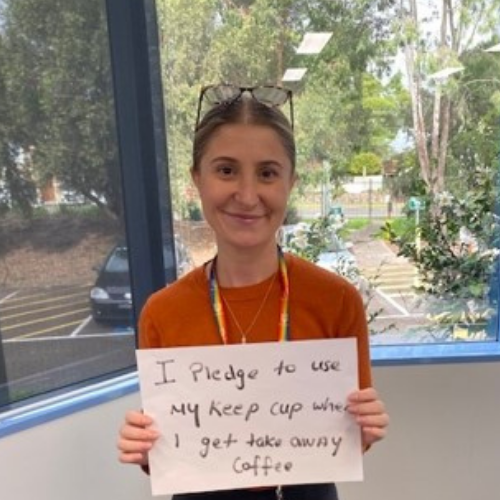

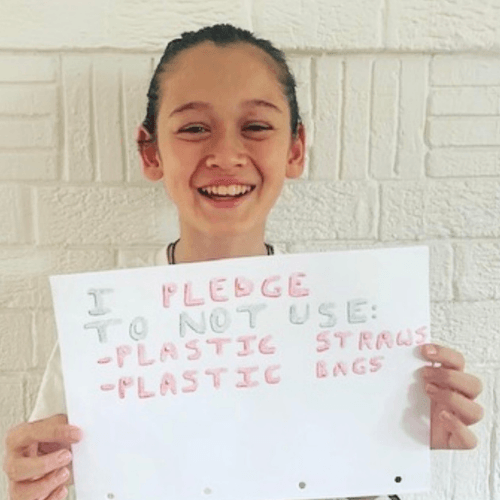

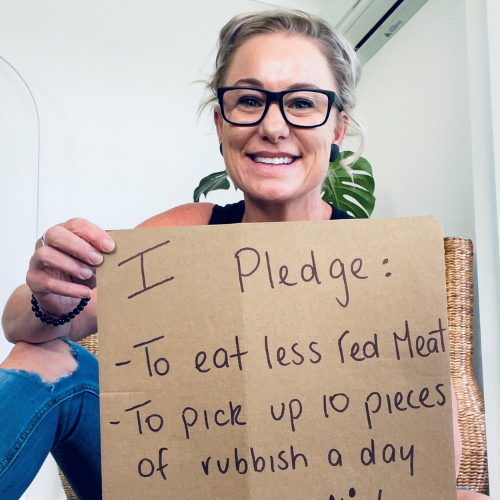

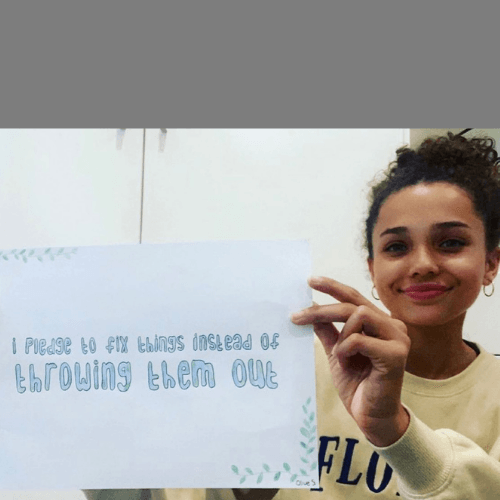

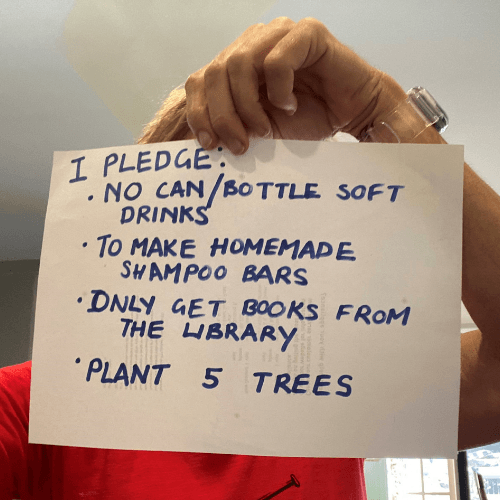

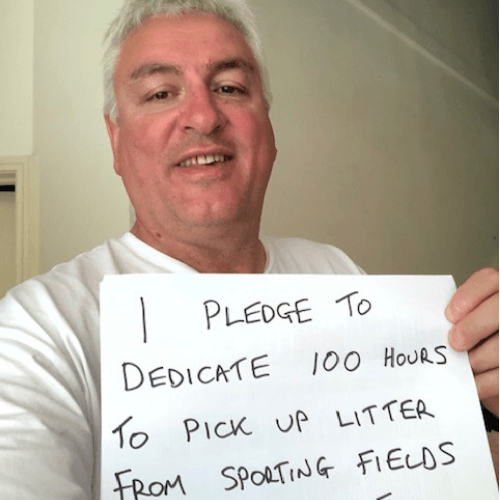

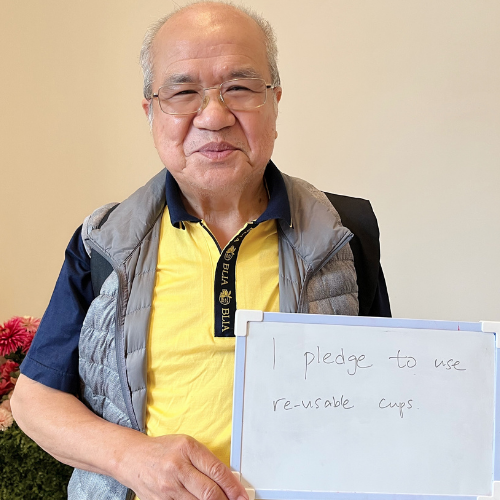

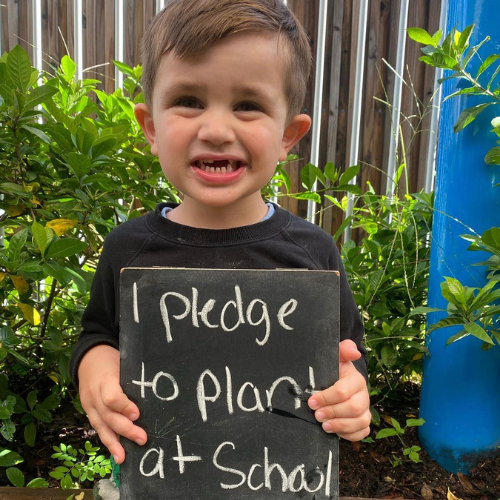

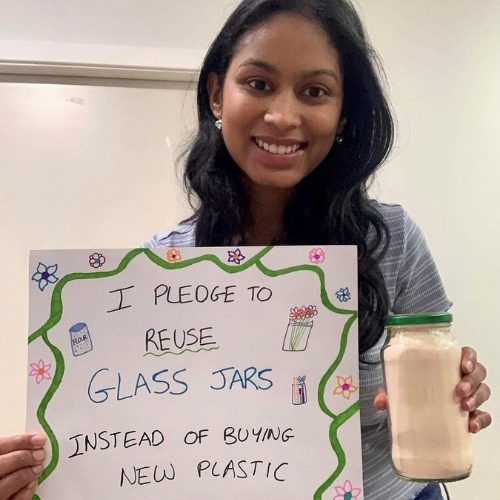

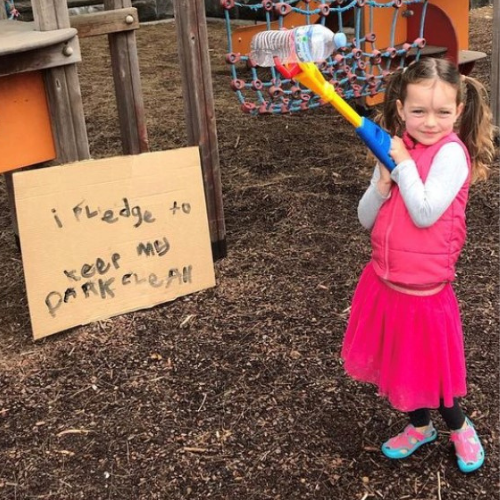

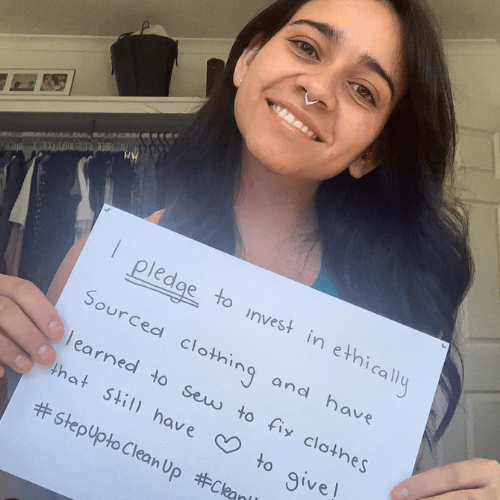

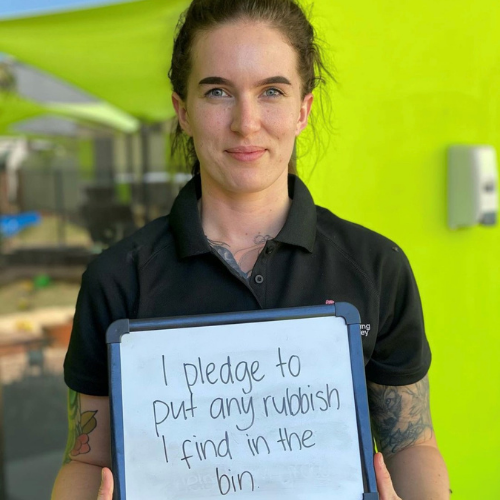

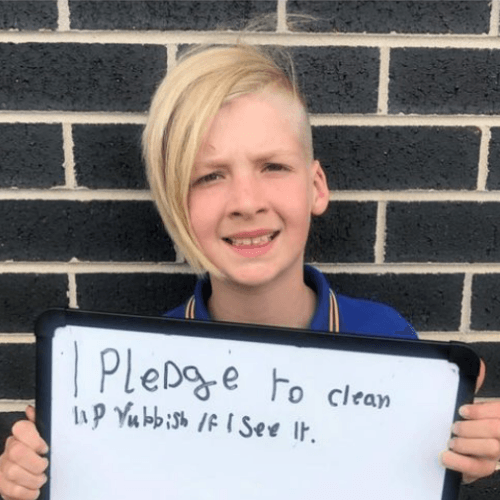

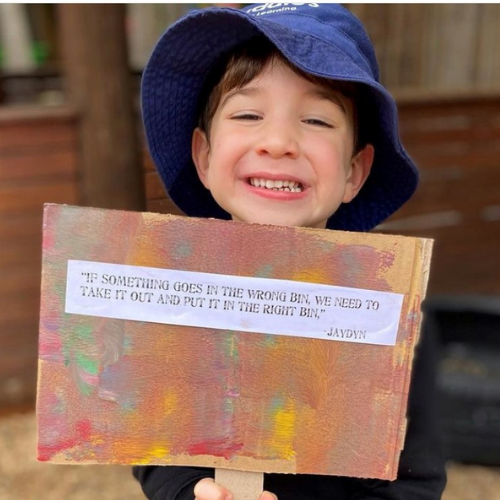

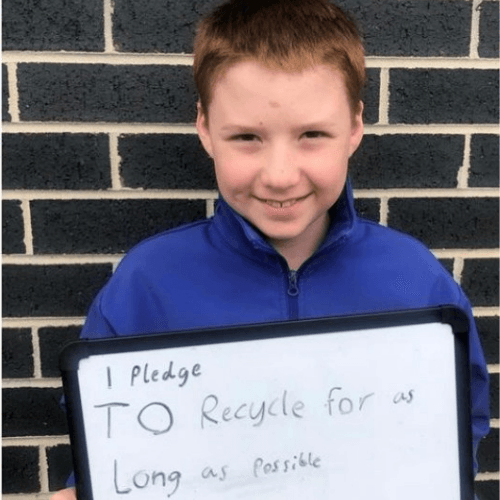

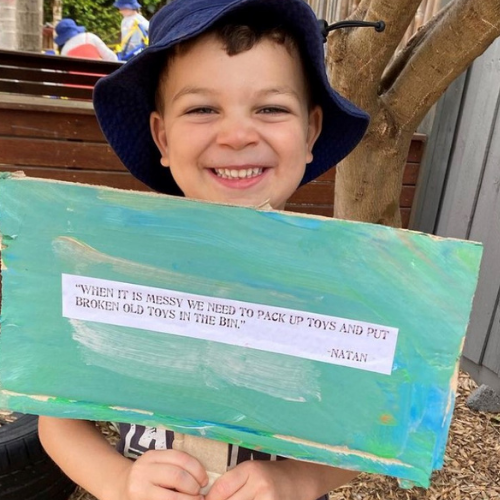

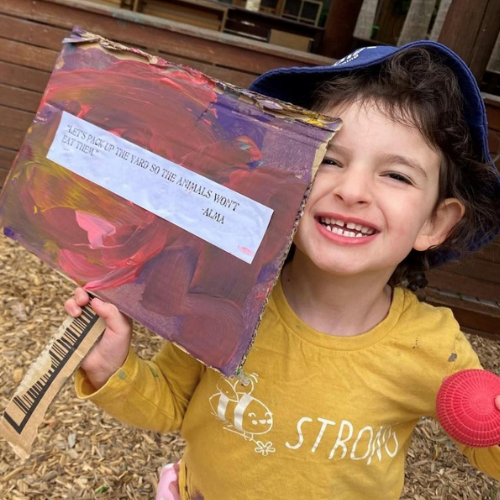

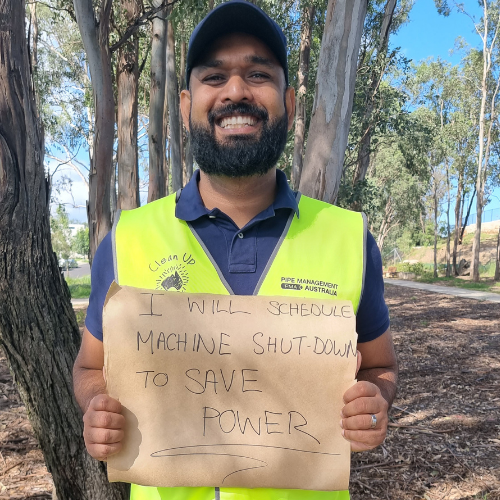

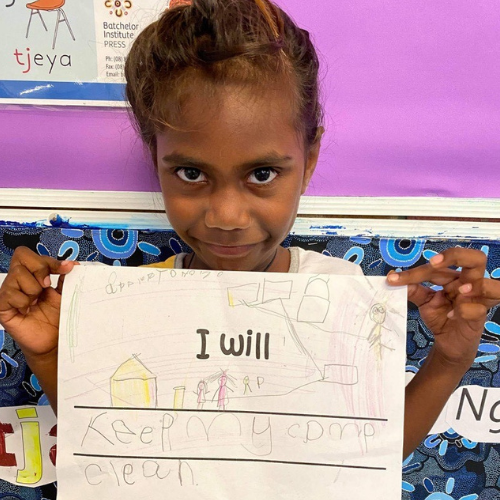

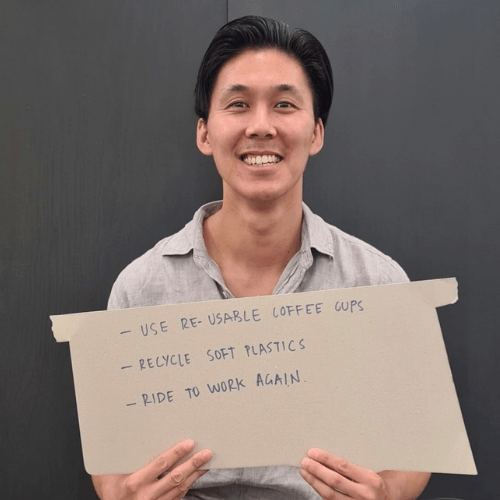

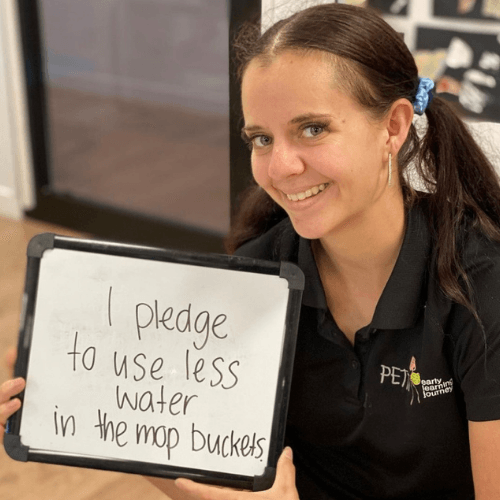

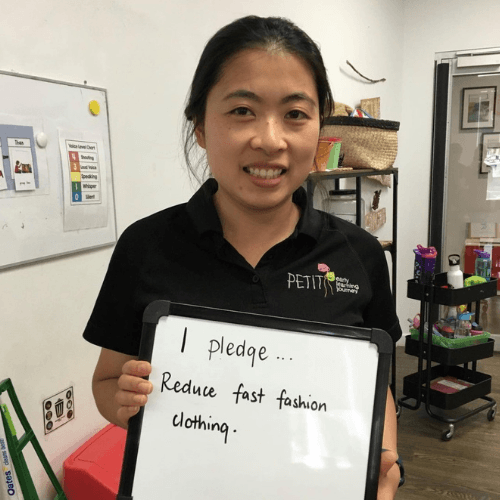

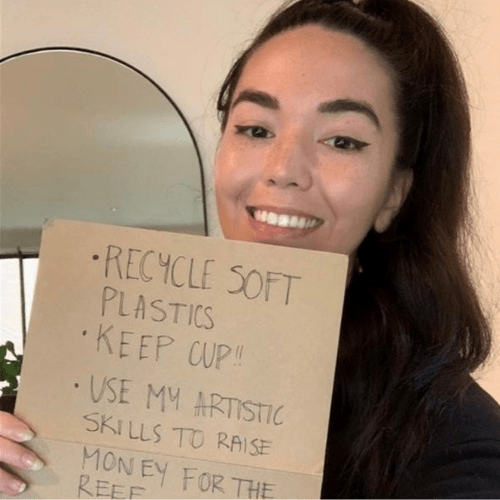

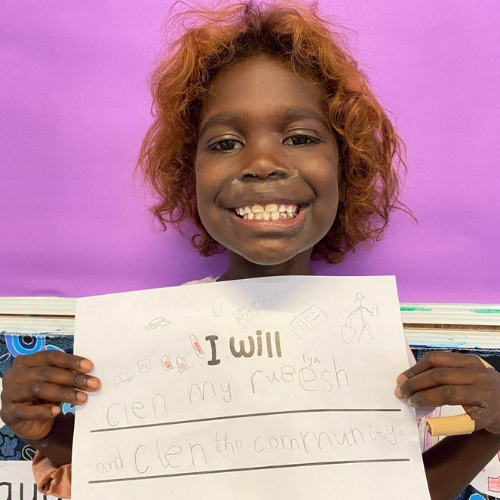

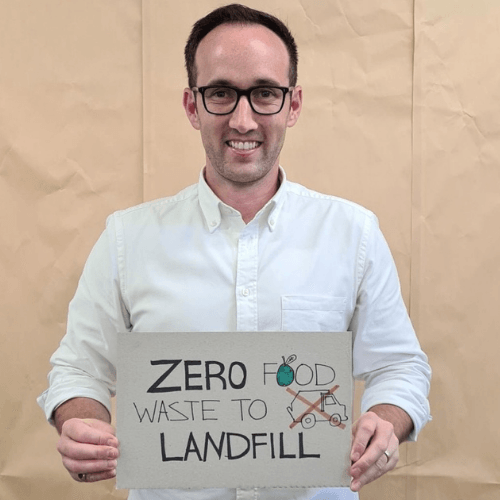

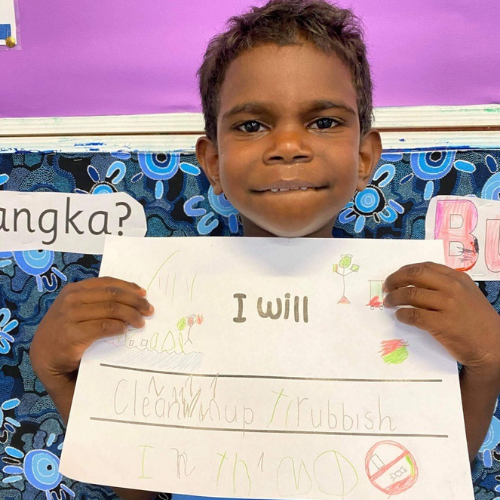

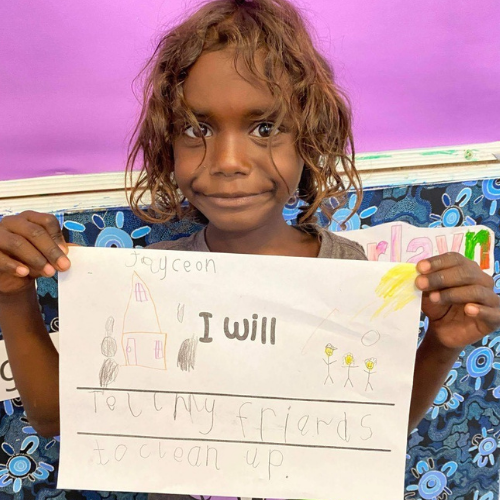

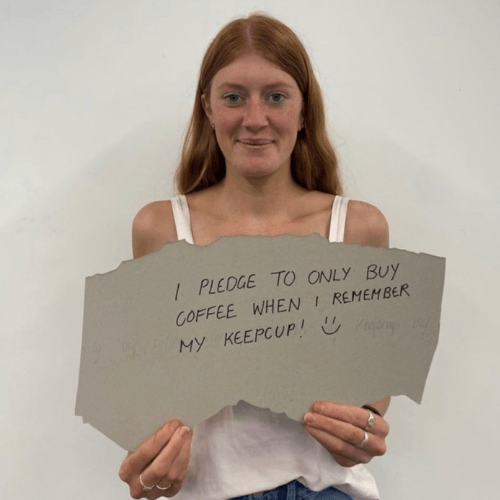

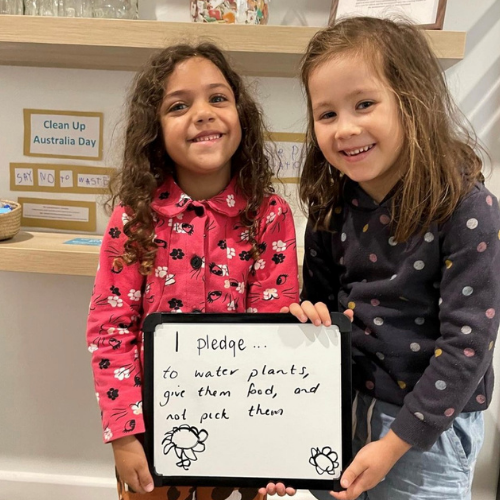

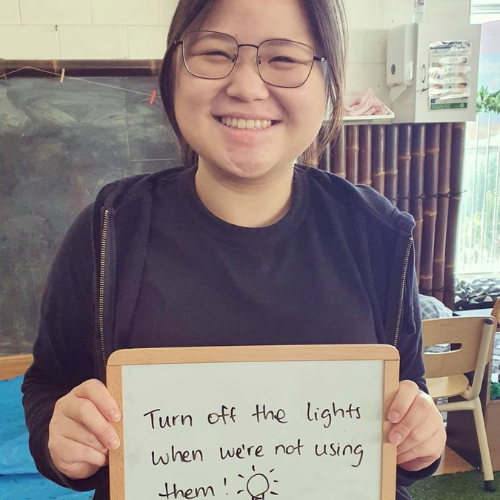

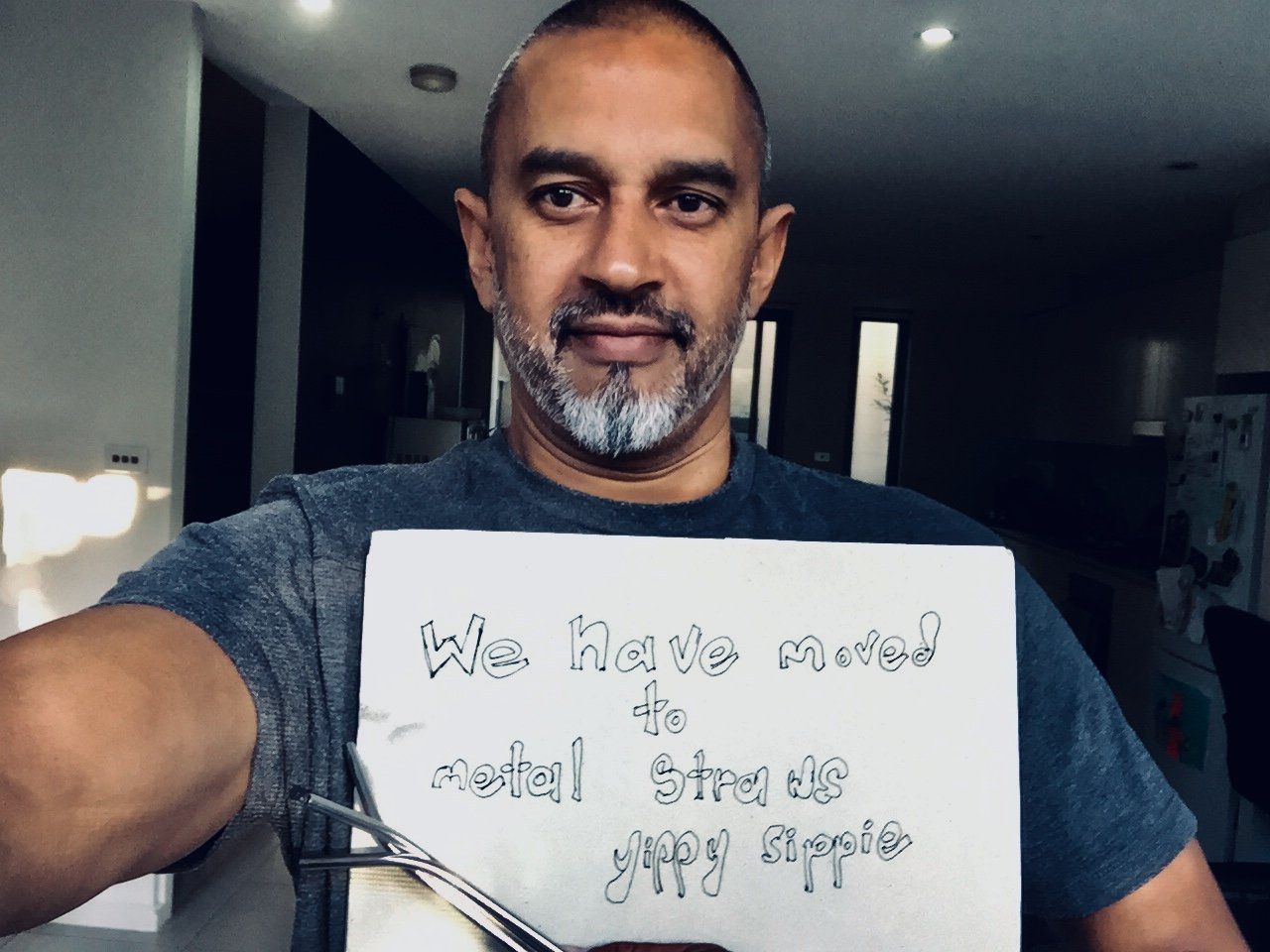

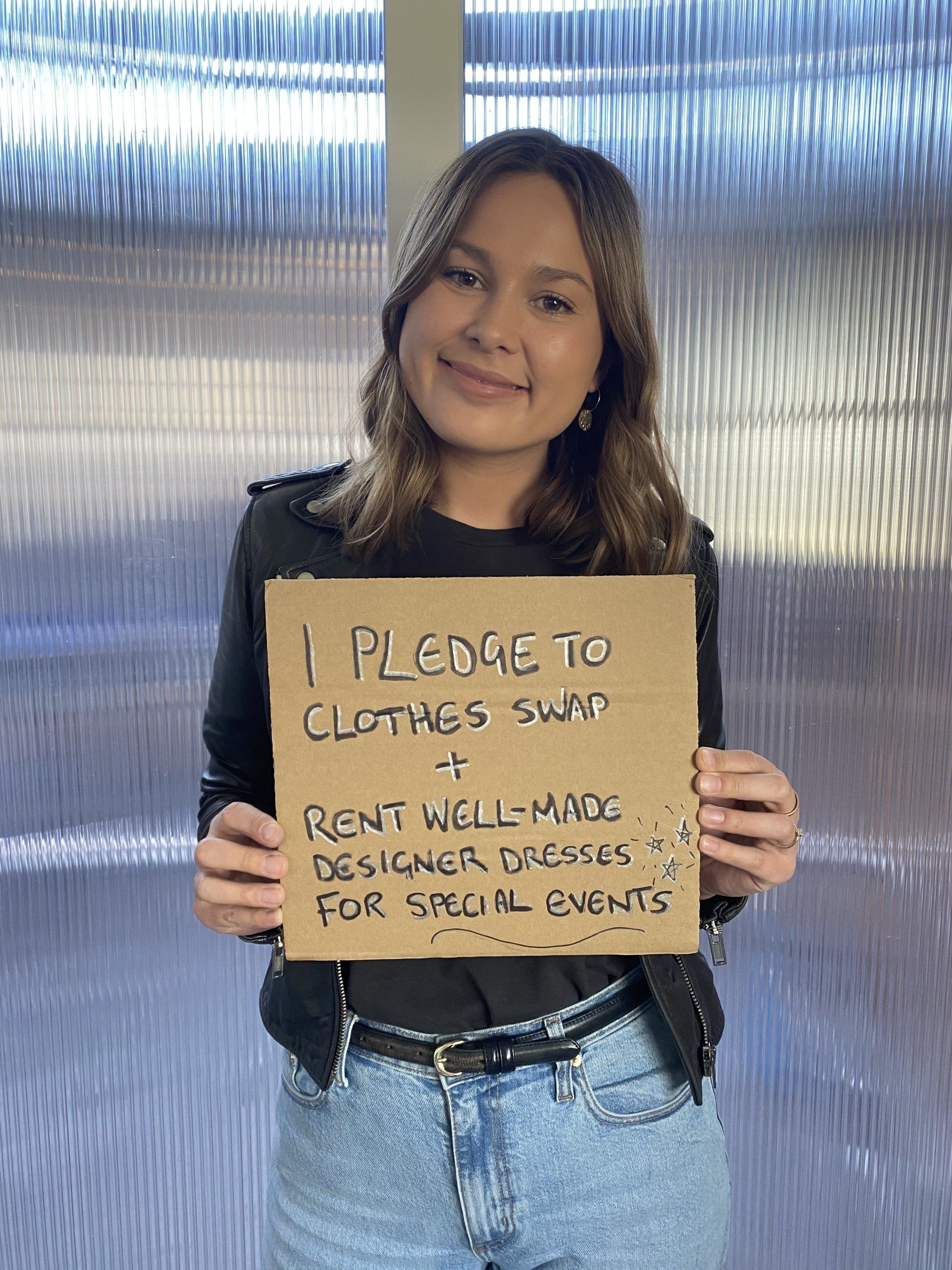

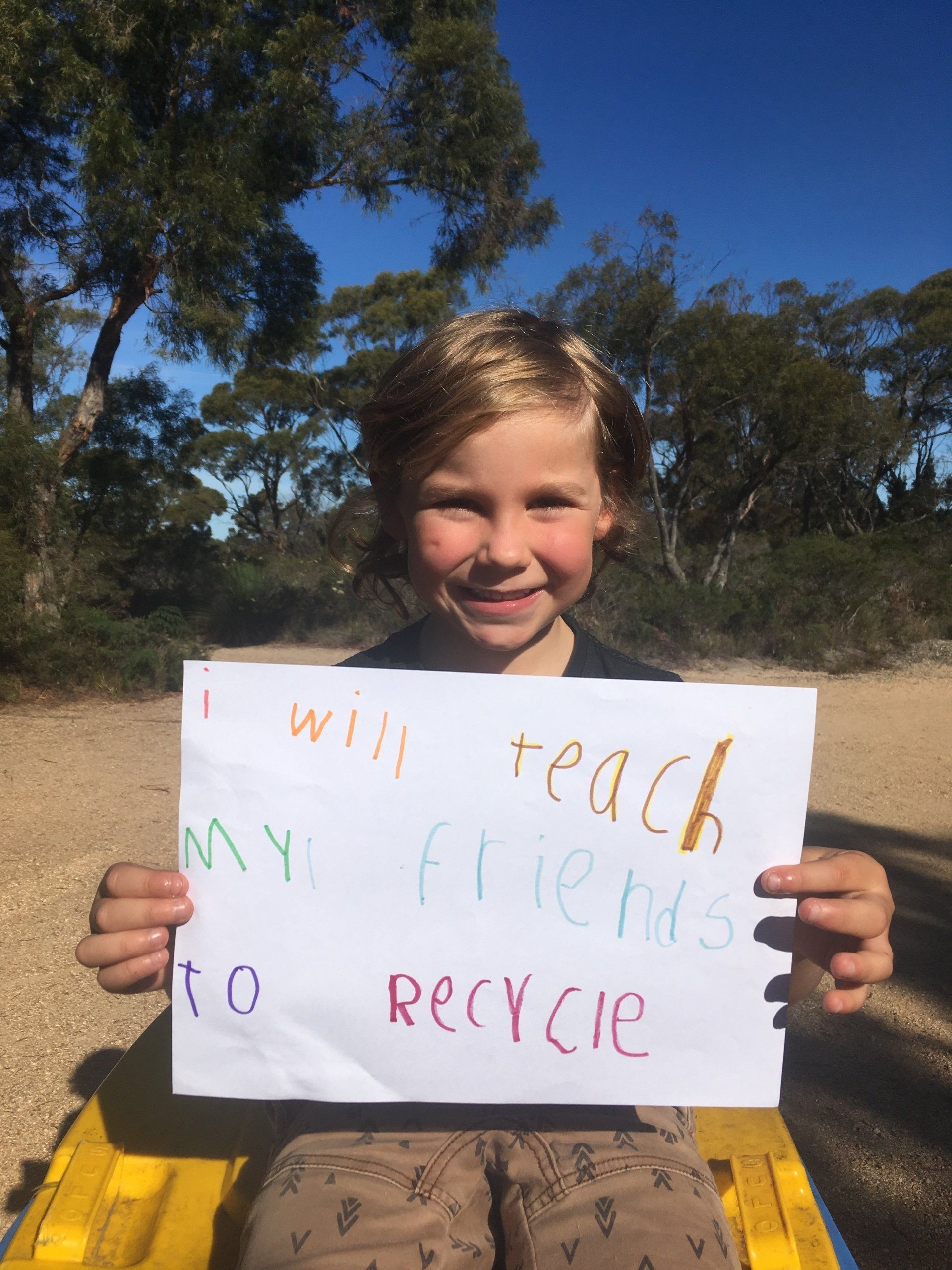

Inspire your family and friends to make a change by sharing your pledge and tagging @CleanUpAustralia #CleanUpAustralia

Clean Up Australia

Clean Up Australia acknowledges the Traditional Owners of Country throughout Australia and their continuing connection to land, waters and community. We pay our respects to Elders past and present.