Humorous and in a good mood, how else can it be on the idyllic, sunny island of Oahu, Shana and I stroll through Honolulu’s Chinatown. Shana shows and invites me, a Westerner tourist, through a beautiful part of Honolulu. It leads me to places and places where tourists hardly get lost and when you meet a few, then they are really lost. Chinatown has a special character and flair, be it the old architecture of the buildings, the bright colors, the cultures, the detachment and yet the warm friendliness of the people and the special smell. It is definitely another indescribably beautiful world. We walked through the narrow streets after other small goods stores, overflowed, even sprinkled, with merchandise and junk, were lined up next to each other. Certainly the traders have struck up a competition among themselves as to who can store the most commodities in his shop. The arched shelves are so crushed by weight that it is life-threatening to come near them. Every little space that can be found in these Chinese shops is perfectly used, so the dealers and salespeople almost have to stand outside their shops. Now we have entered a large market hall, where there is a huge, noisy hustle and bustle. If you take a deep breath here, a sea of the most diverse, exotic, sweet, fragrant and indescribable scents caresses your nose. There are several fish stalls with the most unusual, colorful and the size of fish and crabs, there vegetable stalls from all over the world, piled sacks of rice on the left, roasted whole ducks and chickens here, there unknown food here and there, different Chinese food stalls, takeaways and restaurants, flowers and a huge variety of brightly colored Hawaiian lei’s and loads, really loads of fruits. A land of milk and honey for fruit and food lovers in general. For me the market hall was a huge museum, where I saw all the food there is on earth in one hall. You really have to see this once in a lifetime, what a selection of fruits, vegetables and fish there is in the middle of the Pacific. Dreamlike! So I was amazed at the size of a fruit and was totally unknown to me. Shana only said to me that this was the breadfruit, where earlier in history the first natives were on their way to discover the Pacific, as was always taken by European seafarers on voyages of discovery. This is how the breadfruit spread across the Pacific. I find this an extraordinary, exciting fruit and that’s why I researched it on the Internet. „National Tropical Botanical Garden“ of Hawaii has a terrific description of this fruit, which I would like to share here:

About Breadfruit

There are different species and hundreds of varieties with the potential to improve food security and reforest lands made barren by development and natural disasters. When studying the botany and ethnobotany of breadfruit trees, researchers find the physiology, structure, and genetic make-up of these trees as diverse and fascinating as the different cultures that have used them for survival for thousands of years.

By conserving these trees in our living collection and in vitro in laboratories, we preserve a critical resource that has led to the distribution and cultivation of trees to alleviate hunger and poverty, and reserve their place in history.

Breadfruit is an energy-rich food and a good source of complex carbohydrates, fiber, and minerals such as potassium, calcium, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, manganese, and zinc. This nutritious fruit also provides B vitamins, niacin, thiamine, and Vitamin C. Some varieties have high levels of provitamin A carotenoids, nutrients essential to good health.

Breadfruit is an energy-rich food and a good source of complex carbohydrates, fiber, and minerals such as potassium, calcium, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, manganese, and zinc. This nutritious fruit also provides B vitamins, niacin, thiamine, and Vitamin C. Some varieties have high levels of provitamin A carotenoids, nutrients essential to good health.

Breadfruit is gluten free and its protein is complete, providing all of the essential amino acids necessary for human health. In a world with nearly 1 billion hungry people, 80% of whom live in the tropics, the conservation, study and use of breadfruit is extremely relevant today.

Breadfruit is an important component in traditional agroforestry systems and can be grown with a wide range of plants. Trees begin to bear fruit in three to five years, producing for many decades. The trees require little attention or care, producing an abundance of food with minimal input of labor or materials, and thrive under a wide range of ecological conditions.

Breadfruit trees provide food security, and contribute to diversified regenerative agriculture and agroforestry, improved soil conditions and watersheds, and valuable environmental benefits including reduction of CO2. They also give shelter and food to important plant pollinators and seed dispersers such as honeybees, birds, and fruit bats. In addition to health and environmental benefits, breadfruit trees can provide economic opportunities.

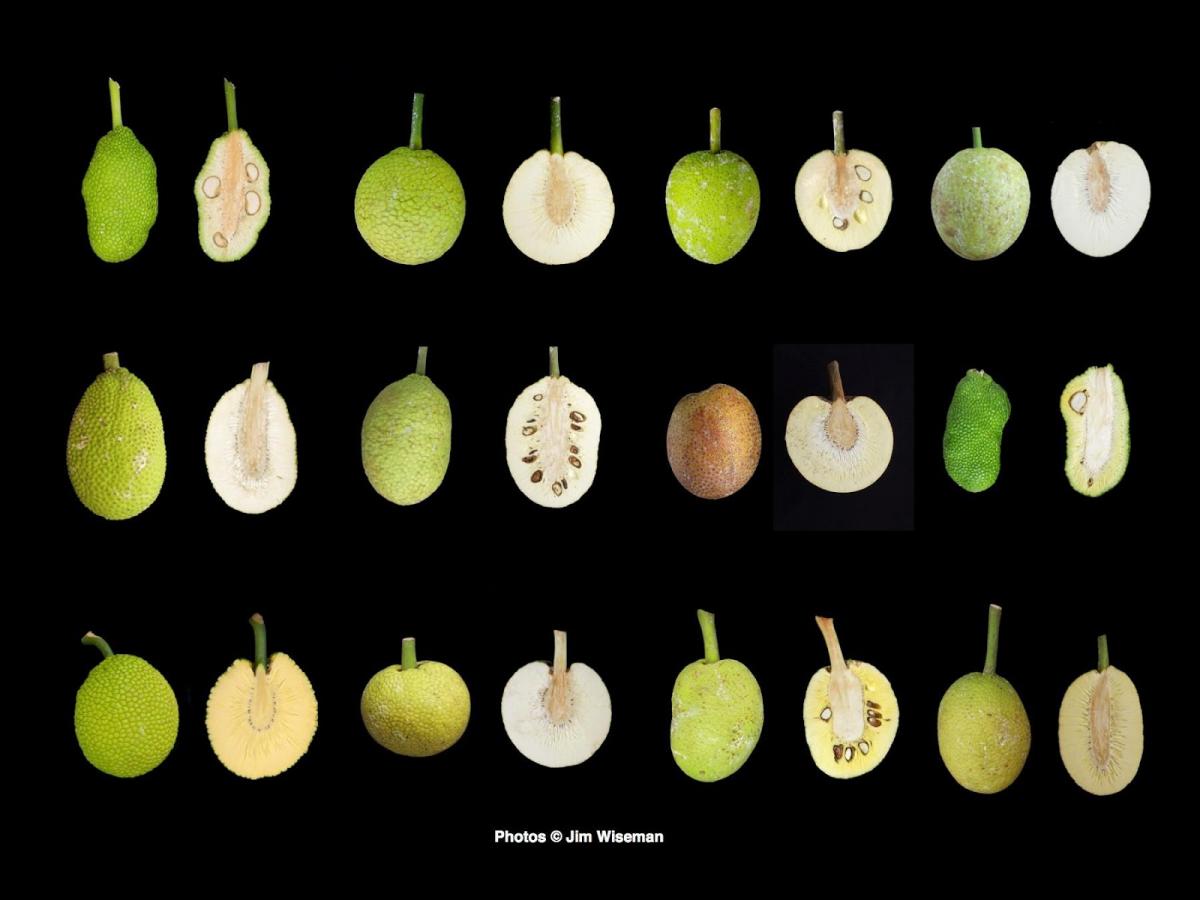

Varieties

There are hundreds of known varieties (cultivars) of breadfruit in our world today and more yet to be recorded. Breadfruit trees are as diverse as they are vital. Trees produce fruit that look completely different when compared to another cultivar, ranging from dark green and weighing as much as a watermelon, to lavender color and apple-sized. Leaves are long and slender with deep, curving lobes to wide and round with barely any lobes at all.

Cultivars not only differ in appearance (morphology); they also vary in flavor, texture, nutritional composition, timing of fruit production, tree size and shape, and suitability to various growing conditions. Crop biodiversity increases ecosystem productivity and human health, further reinforcing the importance of studying and conserving these unique and useful cultivars.

Our Collection

Breadfruit is the signature tree of the National Tropical Botanical Garden and its emblematic logo. The breadfruit collection was established in the 1970s with the vision of creating a definitive genebank of breadfruit and breadnut. The Breadfruit Institute is responsible for curating the world’s largest repository of breadfruit diversity with 150 cultivars conserved today.

Breadfruit is the signature tree of the National Tropical Botanical Garden and its emblematic logo. The breadfruit collection was established in the 1970s with the vision of creating a definitive genebank of breadfruit and breadnut. The Breadfruit Institute is responsible for curating the world’s largest repository of breadfruit diversity with 150 cultivars conserved today.

Species

Three related species—Artocarpus altilis (Parkinson) Fosberg, Artocarpus camansi Blanco, and Artocarpus mariannensis Trécul—make up what is known as the “breadfruit complex.” They are members of the Moraceae (fig) family. The nutritious fruit and seeds of all three species are edible. The multipurpose trees are easy to grow, beneficial to the environment, and produce an abundance of nutritious, tasty fruit. They also provide construction materials, medicine, fabric, glue, insect repellent, animal feed, and more. The trees begin bearing in 3 to 5 years and are productive for many decades. This ‘tree of bread’ has the potential to play a significant role in alleviating hunger in the tropics.

Breadfruit: Artocarpus altilis (Parkinson) Fosberg

The scientific or Latin name of breadfruit is derived from Greek (artos = bread, karpos = fruit), and altilis means ‘fat’. Baked or roasted in a fire, the fruit has a starchy texture and fragrance that is reminiscent of fresh baked bread. Breadfruit has been an important staple crop and primary component of traditional agroforestry systems in the Pacific for more than 3,000 years. This species originated in the South Pacific and was spread throughout Oceania by intrepid islanders settling the numerous islands of Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Hundreds of varieties have been cultivated and more than 2,000 names have been documented.

The tree is grown on most Pacific Islands, with the exception of New Zealand and Easter Island. It is now cultivated throughout the tropics. Due to the efforts of Captain Bligh and French voyagers, a few seedless varieties from Polynesia were introduced to the Caribbean in the late 1700s. These Polynesian varieties were then spread throughout the Caribbean and to Central and South America, Africa, India, Southeast Asia, Madagascar, the Maldives, the Seychelles, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, northern Australia, and south Florida. Breadfruit is now grown in close to 90 countries. Breadfruit is a versatile crop and the fruit can be cooked and eaten at all stages of maturity. The seeds are also edible when cooked.

The tree is grown on most Pacific Islands, with the exception of New Zealand and Easter Island. It is now cultivated throughout the tropics. Due to the efforts of Captain Bligh and French voyagers, a few seedless varieties from Polynesia were introduced to the Caribbean in the late 1700s. These Polynesian varieties were then spread throughout the Caribbean and to Central and South America, Africa, India, Southeast Asia, Madagascar, the Maldives, the Seychelles, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, northern Australia, and south Florida. Breadfruit is now grown in close to 90 countries. Breadfruit is a versatile crop and the fruit can be cooked and eaten at all stages of maturity. The seeds are also edible when cooked.

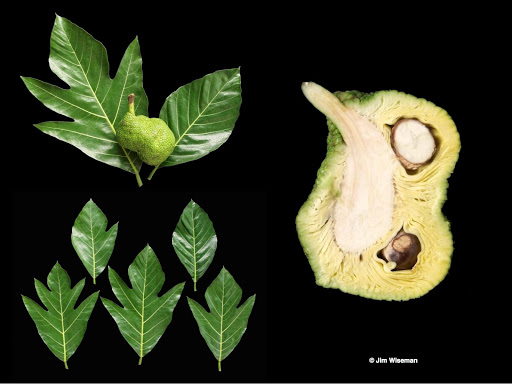

Description

An evergreen tree (12-15 m up to 21 m), breadfruit tends to have a denser, more spreading canopy than Artocarpus camansi. Leaves (15-60 cm or longer) are almost entire to deeply dissected with 1-6 pairs of lobes. Fruit (10-30 cm long × 9-20 cm wide) vary in shape, size, and skin texture. They are usually round, oval or oblong weighing 0.25-6 kg. Skin texture ranges from smooth to rough to spiny. The color is light green, yellowish-green or yellow when mature, although one unusual variety (‘Afara’ from French Polynesia) has pinkish or orange-brown skin. The flesh is creamy white to pale yellow. Fruit are typically mature and ready to cook and eat as a starchy staple in 15-20 weeks. Ripe fruit have yellow or yellow-brown skin and soft, sweet, creamy flesh that can be eaten raw or cooked. Fruit contain no to many seeds depending upon the variety. Seeds have a pale to dark brown seed coat. Seeds germinate immediately and cannot be dried or stored. They are rarely used for propagation. Breadfruit is usually vegetatively propagated using root shoots or root cuttings.

Common names

- árbol de pan, fruta de pan, pan, panapen, (Spanish)

- arbre à pain, fruit à pain (French)

- beta (Vanuatu)

- bia, bulo, nimbalu (Solomon Islands)

- blèfoutou, yovotévi (Bénin)

- breadfruit (English)

- brotfruchtbaum (German)

- broodvrucht, broodboom (Dutch)

- cow, panbwa, pain bois, frutapan, and fruta de pan (Caribbean)

- fruta pao, pao de massa (Portuguese)

- kapiak (Papua New Guinea)

- kuru (Cook Islands)

- lemai, lemae (Guam, Mariana Islands)

- mazapan (Guatemala, Honduras)

- meduu (Palau)

- mei, mai (Federated States of Micronesia, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Marquesas, Tonga, Tuvalu)

- mos (Kosrae)

- rata del (Sri Lanka)

- rimas (Philippines)

- shelisheli (Tanzania)

- sukun (Indonesia, Malaysia)

- ‘ulu (Hawai‘i, Samoa, Rotuma, Tuvalu)

- ‘uru (Society Islands)

- uto, buco (Fiji)

Breadnut: Artocarpus camansi Blanco

Breadnut is native to New Guinea, and possibly the Moluccas (Indonesia) and the Philippines. This species is propagated by seed. In New Guinea, it is widely scattered in alluvial forests in lowland areas and naturally spread by birds and fruit bats that feed on the fruit and drop the large seeds. It is also cultivated in home gardens. It only occurs in cultivation in the Philippines where it is typically grown as a backyard tree. Breadnut is often considered to be a form of seeded breadfruit. However, it is a separate species and the ancestor of seeded and seedless breadfruit (A. altilis)

Breadnut is native to New Guinea, and possibly the Moluccas (Indonesia) and the Philippines. This species is propagated by seed. In New Guinea, it is widely scattered in alluvial forests in lowland areas and naturally spread by birds and fruit bats that feed on the fruit and drop the large seeds. It is also cultivated in home gardens. It only occurs in cultivation in the Philippines where it is typically grown as a backyard tree. Breadnut is often considered to be a form of seeded breadfruit. However, it is a separate species and the ancestor of seeded and seedless breadfruit (A. altilis)

Breadnut is infrequently grown in the Pacific outside of its native range. A few trees are now found in New Caledonia, Pohnpei, FSM, the Marquesas, Tahiti, Palau, and Hawaii, introduced by immigrants from the Philippines in recent years. While breadnut is uncommon in Oceania, it has long been grown and used in other tropical regions. Beginning in the late 1700s, the French spread breadnut throughout the tropics and it is now widespread in the Caribbean, Central and South America, Southeast Asia, and West Africa.

Breadnut is infrequently grown in the Pacific outside of its native range. A few trees are now found in New Caledonia, Pohnpei, FSM, the Marquesas, Tahiti, Palau, and Hawaii, introduced by immigrants from the Philippines in recent years. While breadnut is uncommon in Oceania, it has long been grown and used in other tropical regions. Beginning in the late 1700s, the French spread breadnut throughout the tropics and it is now widespread in the Caribbean, Central and South America, Southeast Asia, and West Africa.

Description

The tree grows up to 20 m tall. It typically forms buttresses at the base of the trunk and has a more open canopy than Artocarpus altilis or A. mariannensis. Leaves are large (40-60 cm long) and moderately dissected with 4-6 pairs of lobes. The oblong, spiky fruit is dull green to greenish-brown when ripe. As evident by the name, this species is mostly grown for the numerous large, nutritious seeds or “nuts.” The immature fruit and seeds are often consumed as a vegetable in soups, stews, or salads after the entire fruit is thinly sliced, then boiled. The seeds can be boiled or roasted and resemble chestnuts in texture and flavor.

The tree grows up to 20 m tall. It typically forms buttresses at the base of the trunk and has a more open canopy than Artocarpus altilis or A. mariannensis. Leaves are large (40-60 cm long) and moderately dissected with 4-6 pairs of lobes. The oblong, spiky fruit is dull green to greenish-brown when ripe. As evident by the name, this species is mostly grown for the numerous large, nutritious seeds or “nuts.” The immature fruit and seeds are often consumed as a vegetable in soups, stews, or salads after the entire fruit is thinly sliced, then boiled. The seeds can be boiled or roasted and resemble chestnuts in texture and flavor.

Common Names

- breadnut (English)

- castaña (Spanish)

- chataigne (Caribbean)

- chataignier (French)

- dulugian, kamansi, kolo, pakau, ugod (Philippines)

- kapiak (New Guinea)

- kos del (Sri Lanka)

- mei kakano (Marquesas)

- pana de pepitas (Puerto Rico)

- kelur, kulor, kulur, kuror, timbul (Indonesia, Malaysia)

Dugdug or Chebiei: Artocarpus mariannensis Trécul

This wild seeded breadfruit relative is native to Palau and the Mariana Islands where it grows in limestone and ravine forests from the coast to lower mountain slopes. It is distributed through its natural range by fruit bats. Wild populations are seriously declining due to typhoon damage, predation by feral deer, and the disappearance of fruit bats. It has naturally hybridized with A. altilis and the numerous interspecific hybrid varieties are considered to be ‘breadfruit’, whether they are seeded or seedless.

This wild seeded breadfruit relative is native to Palau and the Mariana Islands where it grows in limestone and ravine forests from the coast to lower mountain slopes. It is distributed through its natural range by fruit bats. Wild populations are seriously declining due to typhoon damage, predation by feral deer, and the disappearance of fruit bats. It has naturally hybridized with A. altilis and the numerous interspecific hybrid varieties are considered to be ‘breadfruit’, whether they are seeded or seedless.

Artocarpus mariannensis and hybrid varieties are a major staple food tree and widely cultivated throughout Palau, Mariana Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Kiribati, Republic of the Marshall Islands, Tokelau, Tuvalu, Nauru, and Banaba Island. They are not grown elsewhere in the Pacific or other tropical regions except for a few trees in Hawaii and Rabi Island in Fiji, the latter introduced in the 1940s from Banaba. Hybrid varieties may be well suited for other atoll countries and coastal areas in the tropics because they are better adapted to sandy soils and saline conditions than most seedless A. altilis breadfruit varieties.

Description

Trees of Artocarpus mariannensis and hybrid varieties can reach heights of 20 m or more. They tend to be more massive than breadfruit and breadnut, with large trunks 2 m wide at the base, extensive buttresses, and full, rounded canopies. They also tolerate salinity better. Leaves are typically entire or shallowly dissected with 1-3 lobes on the upper third of blade. The fruit is small, weighing 0.25-0.5 kg with dark green skin— even when ripe—with a pebbly texture. The flesh is deep yellow when ripe, with a sweet aroma and flavor. The fruit is not as solid or dense as breadfruit and contains few to many rounded dark brown, shiny seeds. This species is seed propagated.

Trees of Artocarpus mariannensis and hybrid varieties can reach heights of 20 m or more. They tend to be more massive than breadfruit and breadnut, with large trunks 2 m wide at the base, extensive buttresses, and full, rounded canopies. They also tolerate salinity better. Leaves are typically entire or shallowly dissected with 1-3 lobes on the upper third of blade. The fruit is small, weighing 0.25-0.5 kg with dark green skin— even when ripe—with a pebbly texture. The flesh is deep yellow when ripe, with a sweet aroma and flavor. The fruit is not as solid or dense as breadfruit and contains few to many rounded dark brown, shiny seeds. This species is seed propagated.

The numerous hybrid varieties in Micronesia exhibit great variability in fruit and leaf form and can be seeded or seedless. The fruit are typically rough-skinned or pebbly, with light to dark green glossy skin, and creamy white to yellow flesh. The flesh is not as solid or dense as seedless Polynesian breadfruit varieties. Seeded varieties typically have lumpy, asymmetrical fruit 12-30 cm long. Some unusual forms have narrow, elongated fruit up to 45 cm long. Most seeded hybrid varieties are unique to a particular area since they are local seedling selections. Some varieties, such as seedless ‘Meinpadahk’, are widely distributed and grow on high islands and coral atolls.

Common Names

- chebiei, ebiei, meduuliou, mai (Palau)

- dugdug, dokdok (Mariana Islands)

- maiyah (Puluwat, Yap)

- Marianas breadfruit, seeded breadfruit (English)

- mei chocho (Chuuk)

- mei kole (Pohnpei)

- mejwaan (Marshall Islands)

- mos en Kosrae (Kosrae)

- te mai (Kiribati)

Botany

Scientific study of breadfruit is essential to a greater understanding of plant cultivation, care, and production. Researching the physiology, structure, genetics, and ecology of breadfruit trees has provided vital information to maximize potential in alleviating hunger and combating deforestation. Without studying the botany of breadfruit, we would never know a single breadfruit tree can produce food for more than 50 years, and needs no pollination to produce fruit.

Scientific study of breadfruit is essential to a greater understanding of plant cultivation, care, and production. Researching the physiology, structure, genetics, and ecology of breadfruit trees has provided vital information to maximize potential in alleviating hunger and combating deforestation. Without studying the botany of breadfruit, we would never know a single breadfruit tree can produce food for more than 50 years, and needs no pollination to produce fruit.

Flowers

Breadfruit is monoecious with male and female flowers developing on the same tree at the end of branches. The male inflorescence (flower) typically appears first. It is club shaped, ranging from 10 cm to 45 cm long. The inflorescence consists of thousands of tiny, creamy yellow individual flowers attached to a spongy core. The inflorescence fades to dark brown with age. Pollen is shed 10 to 15 days after the emergence of the male inflorescence for a period of about four days. Honeybees are attracted to the abundant pollen produced by some varieties. Each female inflorescence consists of 1500–2000 reduced flowers attached to a spongy core. The flowers fuse together and develop into the fleshy, edible portion of the fruit.

Breadfruit is monoecious with male and female flowers developing on the same tree at the end of branches. The male inflorescence (flower) typically appears first. It is club shaped, ranging from 10 cm to 45 cm long. The inflorescence consists of thousands of tiny, creamy yellow individual flowers attached to a spongy core. The inflorescence fades to dark brown with age. Pollen is shed 10 to 15 days after the emergence of the male inflorescence for a period of about four days. Honeybees are attracted to the abundant pollen produced by some varieties. Each female inflorescence consists of 1500–2000 reduced flowers attached to a spongy core. The flowers fuse together and develop into the fleshy, edible portion of the fruit.

Fruit

Each breadfruit is a compound or multiple fruit called a syncarp. The female inflorescence, appearing after the male, consists of 1500-2000 minute flowers attached to a spongy core. The flowers fuse together and develop into the fleshy, edible portion of the fruit. No pollination is required for a fruit to form. The skin is light to dark green, yellow-green, or yellow when mature, although one unusual variety has pinkish or orange-brown fruit. The thin skin is patterned with pentagonal or hexagonal markings and can be smooth, bumpy, or spiny. Fruit are typically mature and ready to harvest, cook, and eat in 15-20 weeks. The skin of ripe fruit can be green, but is more typically yellow or yellow-brown. The soft, sweet, creamy flesh can be eaten raw or cooked.

History

Breadfruit originated in New Guinea and the Indo-Malay region and was spread throughout the vast Pacific by voyaging islanders. Europeans discovered breadfruit in the late 1500s. They were amazed and delighted by a tree that produced prolific, starchy fruits that, when roasted in a fire, resembled freshly baked bread in texture and aroma.

“regarding food, if a man plant 10 (breadfruit) trees in his life he would completely fulfill his duty to his own as well as future generations…”

“regarding food, if a man plant 10 (breadfruit) trees in his life he would completely fulfill his duty to his own as well as future generations…”

Sir Joseph Banks, who sailed on HMS Endeavour with Captain Cook to Tahiti in 1769, recognized the potential of breadfruit as a food crop for other tropical areas. He proposed to King George III that a special expedition be commissioned to transport breadfruit plants from Tahiti to the Caribbean. This set the stage for one of the grandest sailing adventures of all time. The ill-fated voyage of HMS Bounty 1787-89, under the command of Captain William Bligh, is an extraordinary tale of mutiny, deceit, courage, and sailing skill. Unfortunately, the hundreds of breadfruit plants collected in Tahiti were all tossed overboard by mutineers.

What is little known, is that Captain Bligh returned to Tahiti on the aptly named HMS Providence to continue the breadfruit voyage. Several Tahitian varieties, and an unknown variety from Timor, were successfully introduced to the Caribbean in 1793, first to the botanic garden on St. Vincent and then to botanic gardens at Bath and Spring Garden and other locations in Jamaica. While many accounts dismiss this epic plant introduction as a failure because this unknown crop was not initially accepted by the islands’ population as a food, subsequent decades and centuries have proved the value of breadfruit to the Caribbean and other tropical areas.

What is little known, is that Captain Bligh returned to Tahiti on the aptly named HMS Providence to continue the breadfruit voyage. Several Tahitian varieties, and an unknown variety from Timor, were successfully introduced to the Caribbean in 1793, first to the botanic garden on St. Vincent and then to botanic gardens at Bath and Spring Garden and other locations in Jamaica. While many accounts dismiss this epic plant introduction as a failure because this unknown crop was not initially accepted by the islands’ population as a food, subsequent decades and centuries have proved the value of breadfruit to the Caribbean and other tropical areas.

The British were not alone in their efforts to bring the breadfruit to their tropical colonies. The French centered their plant introduction efforts at the Pamplemousse Botanical Garden in Mauritius. The breadnut (Artocarpus camansi) was collected in the Philippines in 1776 and sent to French colonies in the Caribbean and elsewhere in the 1780s onwards. A seedless Tongan breadfruit variety, known as kele kele, reached Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Cayenne, French Guiana by the late 1790s.

The British were not alone in their efforts to bring the breadfruit to their tropical colonies. The French centered their plant introduction efforts at the Pamplemousse Botanical Garden in Mauritius. The breadnut (Artocarpus camansi) was collected in the Philippines in 1776 and sent to French colonies in the Caribbean and elsewhere in the 1780s onwards. A seedless Tongan breadfruit variety, known as kele kele, reached Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Cayenne, French Guiana by the late 1790s.

These few breadfruit varieties, and breadnut, made their way to other tropical areas, and today are grown in 90 countries worldwide.

Traditional Uses

Breadfruit is a multipurpose species and all parts of the tree are used. It is an essential component of home gardens and traditional agroforestry systems, creating a lush overstory that shelters a wide range of cultivated and native plants. In the Pacific, breadfruit agroforests have protected mountain slopes from erosion for more than two millennia.

Tree

The trees have a beneficial impact on the natural environment creating organic mulch, shade, and a cooler micro-climate beneath the canopy. They give shelter and food to important pollinators and seed dispersers such as honeybees, birds, and fruit bats. A breadfruit tree yields food, construction materials, medicine, cordage, glue, insect repellent, and animal feed.

The trees have a beneficial impact on the natural environment creating organic mulch, shade, and a cooler micro-climate beneath the canopy. They give shelter and food to important pollinators and seed dispersers such as honeybees, birds, and fruit bats. A breadfruit tree yields food, construction materials, medicine, cordage, glue, insect repellent, and animal feed.

Timber

The trunk of a breadfruit tree may be as large as 2 meters in diameter and grow to a height of 4 meters before branching. The wood is light and durable with a light golden color that darkens with age. It is used for the construction of houses and canoes because it resists termites and marine worms. The hulls of outrigger canoes are often fashioned from a single log and are still made in parts of Micronesia and Melanesia. The wood is carved into attractive bowls, statues, handicrafts, furniture, and other items. Older trees are an important source of firewood, especially on the atoll islands.

Bark

The inner bark, or bast, can be made into bark cloth. In the Pacific, islanders chose branches with new growth and remove the outer bark. After separating the brown outer bark from the white inside bark, the white bark is beaten on a smooth stone to spread it. After the beating process is complete, the bark has become a soft, fibrous cloth that is colored with natural dyes. The inner bark is also traditionally used to make a strong cordage used for building and fishing.

Leaves

The leaves are used as fans, sandpaper for fine woodwork, to wrap foods that are cooked in traditional earth ovens, and as biodegradable plates.

Latex

Sticky white latex (sap) is present in all parts of the tree and has been used for glue, caulk, and even chewing gum. Bees are attracted to and harvest droplets of sap from the surface of the fruit. Bird catchers smeared the latex onto branches to entrap saffron-feathered honeycreepers.

Traditional Medicine

The breadfruit tree was an important part of the native pharmacopoeia in the Pacific Islands. The latex was massaged into the skin to treat broken bones and sprains and bandaged on the spine to relieve sciatica. Crushed leaves are commonly used to treat skin ailments and fungus diseases such as ‘thrush’. Diluted latex, taken internally, treated diarrhea, stomachaches, and dysentery. The sap from the crushed stems of leaves is used to treat ear infections or sore eyes. The root is an astringent and used as a purgative; when macerated it is used as a poultice for skin ailments. The bark is also used to treat headaches in several islands. In the West Indies, the yellowing leaf is brewed into tea and taken to reduce high blood pressure and to relieve asthma. The tea is also thought to control diabetes.

Link:

- University of Hawai’i

- National Tropical Botanical Garden

- Breadfruit Tree – Canoe Plants of Hawai’i

- Physicochemical properties of breadfruit