A pandemic turns out to be an opportune time for illegal loggers. A recent report by Brazilian non-governmental organizations found 464,759 hectares (1.15 million acres) were deforested in the Amazon rainforest between 2019 and 2020, an area three times the size of São Paulo. The analysis reveals that logging has reached the untouched core of the Amazon.

At the start of the COP26 climate talks this week, world leaders promised to stop deforestation by 2030. Although similar pledges have faltered in the past, this one will include almost $19 billion of public and private funds, and is backed by Brazil, Indonesia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo which account for 85% of the world’s forests.

The effort can’t come soon enough for the world’s largest rainforest. The Amazon Environmental Research Institute (Ipam) states that almost 20% of all-time recorded destruction in protected areas of the Amazon (pdf) happened between August 2019 and July 2020. It is estimated that 2.8 million hectares (6.9 million acres) of undesignated areas of the Amazon have been deforested. The enormity of what was destroyed during the pandemic reveals the failures of control systems to keep illegal hardwoods out of the market.

The logging monitoring system developed by Imazon called Simex, is based on satellite imagery. The system expanded operations across the Amazon in 2020, where Imazon was joined by other organizations including the Institute for Forestry and Agricultural Management and Certification (Imaflora). The group formed the Simex report that was released in September 2021.

Where the deforestation of the Amazon is happening

The group of organizations managed to cover seven of the nine states that make up the Brazilian Amazon, that account for most of Brazil’s rainforest timber production. More than half of the logging happened in the state of Mato Grosso, followed by Amazonas and Rondônia. The area covers 10 municipalities in those states along with Roraima, Acre, and Pará.

It’s difficult for researchers to discern which activities are legal and which are not, but they did observe logging operations in undesignated national parks and indigenous territories. The ongoing political climate led by President Jair Bolsonaro has defunded departments and organizations that work to protect those areas.

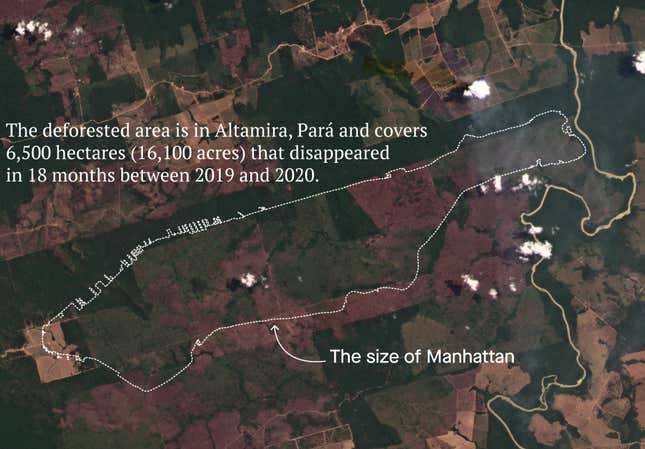

The largest continuous area of deforested Amazon rainforest

Imazon found that of the 50,139 hectares deforested in Pará, a state with intense logging, that 55% of the activity happened without any authorization. To verify legality, Imazon obtained data from the Environmental Licensing and Monitoring System (Simlam-PA) and cross-referenced it with the satellite imagery.

A further investigation by InfoAmazonia identified the location of the largest continuous area of deforestation in the Amazon, confirmed by another satellite imagery platform MapBiomas.

“Illegal logging is the first activity that happens. It opens the frontier and makes it available for future actors,” said Marco Lentini, project coordinator at Imaflora.

The investigation found that the deforestation in Altamira was carried out in a large part by Augustinho Alba who was fined $4.16 million for logging without authorization. It is estimated Alba’s crew cleared 60% of what was cut down and did not stop even after being fined by the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama).

What is wood from the Amazon used for?

While timber from the Amazon is sold at high prices abroad, only about 10% of the wood is exported. The other 90% is sold on the cheap within Brazil for domestic construction. Development is on the rise and cities within the Amazon itself have greater demand for the wood to build homes and industries.

“A lot of the timber from the Amazon is for civil construction, very basic pieces like flooring, decking…it’s pretty much going to housing with very little value added,” said Lentini.

According to Imaflora, it is possible that illegal Amazon timber could be sold for half the price of farmed timber because the costs exclude labor fees, taxes, and other costs authorized producers usually pay for. When management plans authorize felling more trees than exist in an area it allows illegal loggers to conceal a tree’s true origin—known as tree laundering. Licenses can be faked easily and put on the books as legal, and rates can be overestimated to convert logs into sawn wood by timber industries.

“What we are sure of is that 10% of the production comes from concessions in certified areas. The other 90% is gray,” continued Lentini. “How can we influence Brazilians to ask for proof of legal production? I think that’s probably the greatest challenge that we have in the timber market.”