YAYOI KUSAMA: INFINITY MIRRORS at the Art Gallery of Ontario (317 Dundas West). Opening hours vary. $21.50-$30. ago.ca. To May 27. See listing.

What do you see when you look at a selfie? Vanity and narcissism? Or a desire to share and be a part of something larger?

It’s appropriate that Yayoi Kusama’s touring museum show is all about mirrors because reactions to the prolific, 88-year-old Japanese artist’s work reflect a fundamental divide in our culture, which is at a crossroads between individualistic impulses and an awakening to collective responsibility.

Individualist attitudes have risen since the 1960s in tandem with economic prosperity. At the same time, ideas of collective healing and intersectionality are being put forward by politicians and activists fighting for people on the margins.

Others look at this divide as generational. As British cultural historian John Higgs put it, if you see a selfie as “someone smiling at their friends, an attempt to strengthen social bonds, then you’re thinking like the millennial generation. Thinking about the photo without that wider context is a dumb way to see the world, because it fails to explain what is really happening.”

After opening at the Art Gallery of Ontario last week, Infinity Mirrors, a two-floor survey of Kusama’s work focused around six of the artist’s mirrored room installations, inspired the usual hand-wringing around millennial narcissism and about social media spoiling the gallery experience. The AGO is encouraging selfies and social posts, with obvious marketing benefits, but the artist doesn’t mind either.

Over two floors, Infinity Mirrors explores the top-selling living female artist’s philosophy of “self-obliteration,” developed while active in New York City’s art world in the 1950s and 60s. In a way, gallery patrons snapping selfies fits with the show’s focuses on human connection and questioning authority.

“As a Japanese woman, I think Kusama was aware of how prevalent racism and xenophobic feelings were during that time,” explains Infinity Mirrors curator Mika Yoshitake. “There was a very peaceful philosophy with self-obliteration. It was about stripping naked, painting polka dots on each other’s bodies and seeing each other as equal. You are one insignificant figure amongst the vast universe.”

It’s somewhat ironic, since Kusama often avoids aligning herself with wider social movements – like feminism – preferring to be viewed as her own entity. But you can be autonomous while also striving for community and connection.

“She felt like she could be radical without having to force this idea of being a woman even though, innately, she is very powerful and pushes her ideals and rebellious behaviour,” says Yoshitake, adding that Infinity Mirrors’ message is one of “radical connectivity.”

“When you’re in the mirror rooms, it is like discovering different sides of yourself – or multiple modes of being.”

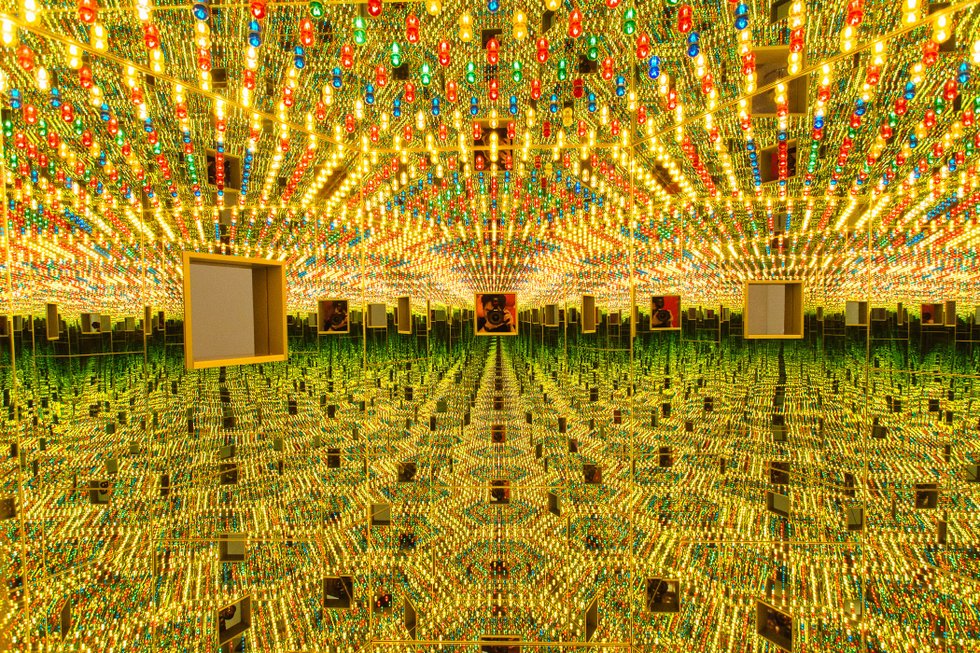

The rooms represent different stages of Kusama’s five-decades-long career. Some rely on playful props, such as glowing ceramic pumpkins and soft sculptures of red-and-white phalli. Others use LED lights to evoke vast star fields that practically cause the visitor to disappear when wearing dark colours. And, yes, the fragmented reflections are more affecting when viewed with the naked eye than through a phone screen.

Tanja-Tiziana

Infinity Mirrored Room – Love Forever (1966/1994)

Tanja-Tiziana

Infinity Mirrored Room – Aftermath Of Obliteration Of Eternity (2009)

Tanja-Tiziana

Close-up of the painting Infinity-net 1 (1958)

Tanja-Tiziana

Narcissus Garden, an installation originally staged during the Venice Biennale in 1966.

Tanja-Tiziana

Ennui (1976), a soft sculpture made from sewn and stuffed fabric with silver paint and shoes.

The exhibition, which originated at Washington, D.C.’s Hirshhorn Museum, is the latest chapter in Kusama’s resurgence following a long period of obscurity. Ripped off by contemporaries like Claes Oldenburg and Andy Warhol, Kusama has always been innovative and ambitious but, until recent years, was unable to overcome art-world sexism and racism. Though the work she produced is now considered game-changing for the pop art and minimalist movements of the day, white men got the credit.

When Yoshitake was putting together Infinity Mirrors, she received a phone call from a random artist who explained that Lucas Samaras was the first artist to do a mirror room at New York’s Pace Gallery in 1966.

“I had to tell him Kusama was actually the one who did it first and he couldn’t believe it,” she says. “It’s a strange reversal. She’s a huge megastar and I don’t think people even know who Lucas Samaras is. But so many retrospectives have foregrounded [the fact that she was copied], so I think she should be happy by now.”

Like many blockbuster art shows, past Infinity Mirrors tour stops have also been criticized for glossing over an artist’s more challenging material. In addition to her Infinity Net paintings, collages, soft sculptures and archival material, the Toronto version of the show is the first to include Kusama’s 16mm film Self-Obliteration, which is full of simulated orgy footage that places the mirrored rooms squarely into the context of the anti-Vietnam War and free-love movements.

Additionally, a satellite exhibition on the second floor restages Kusama’s 1966 Venice Biennale exhibition, Narcissus Garden, in which she attempted to sell mirrored balls by the side of the road for $2 a pop. It was a commentary on the art market, and today it’s a reminder that narcissism predates selfies.

These companion works only sharpen the mirrored rooms’ critique of authority – one that is also reflected by art critics debating whether museums should more tightly control how patrons experience art.

In director Heather Lenz’s documentary Kusama – Infinity, which premiered at Sundance and will open at TIFF Bell Lightbox this spring, Kusama’s New York gallerist Richard Castellane calls the mirrored rooms a “breaking point.” Many artists had explored the concept of infinity but used fixed forms, like painting and sculpture, that allowed viewers to control how they looked at it. Kusama makes paintings, too, many of which are covered in obsessively painted polka dots – her signature.

But with her mirrored rooms, she seizes control of the gaze to disorient viewers.

“The idea of shifting the focus away from an authorial master perspective was central to the philosophies of structuralism in the late 60s,” explains Yoshitake. “Power, authority and totalitarian regimes were being questioned. That destabilization of perspective and maybe even fragmentation of the self was something that was very much embraced.”

Is social media a way for viewers to take back that control, forcing infinity back into a familiar frame? Or does sharing selfies explode the frame even further across vast online networks?

Inside and outside of galleries, systems of authority are being upended by social movements like #MeToo and Black Lives Matter. It’s tempting to read Infinity Mirrors’s upending the gaze as an echo of power struggles in wider culture. Staring into an Infinity Mirror, it becomes clear that narcissism is in the eye of the beholder.

kevinr@nowtoronto.com | @kevinritchie