Contemporary art, by its very nature, encourages unconventional materials. Past exhibitions at CAM have included race cars, money, thousands of tiny succulents, and suspended Tillandsia air plants. One of the Lawrence Abu Hamdan installations currently at the museum, Earwitness Inventory, includes a non-descript metal shelf containing a variety of objects, from pristine white tennis shoes to an assortment of feather dusters to a head of fresh cauliflower. Many of the items placed on the shelf are perishable food items that are replaced regularly. Registrar Jen Nugent changes out the produce twice a week, a curious assortment of edibles that include green coconuts, mini-watermelons, and ripened bananas. “We always have to be aware of the climate in the museum,” Nugent remarks. “If the temperature isn’t right, the food could spoil earlier than anticipated and attract insects.” Early in the run of the exhibition, Nugent made use of photo-documentation to ensure that the objects were going back to the exact spot, but now she has the precise placements memorized.

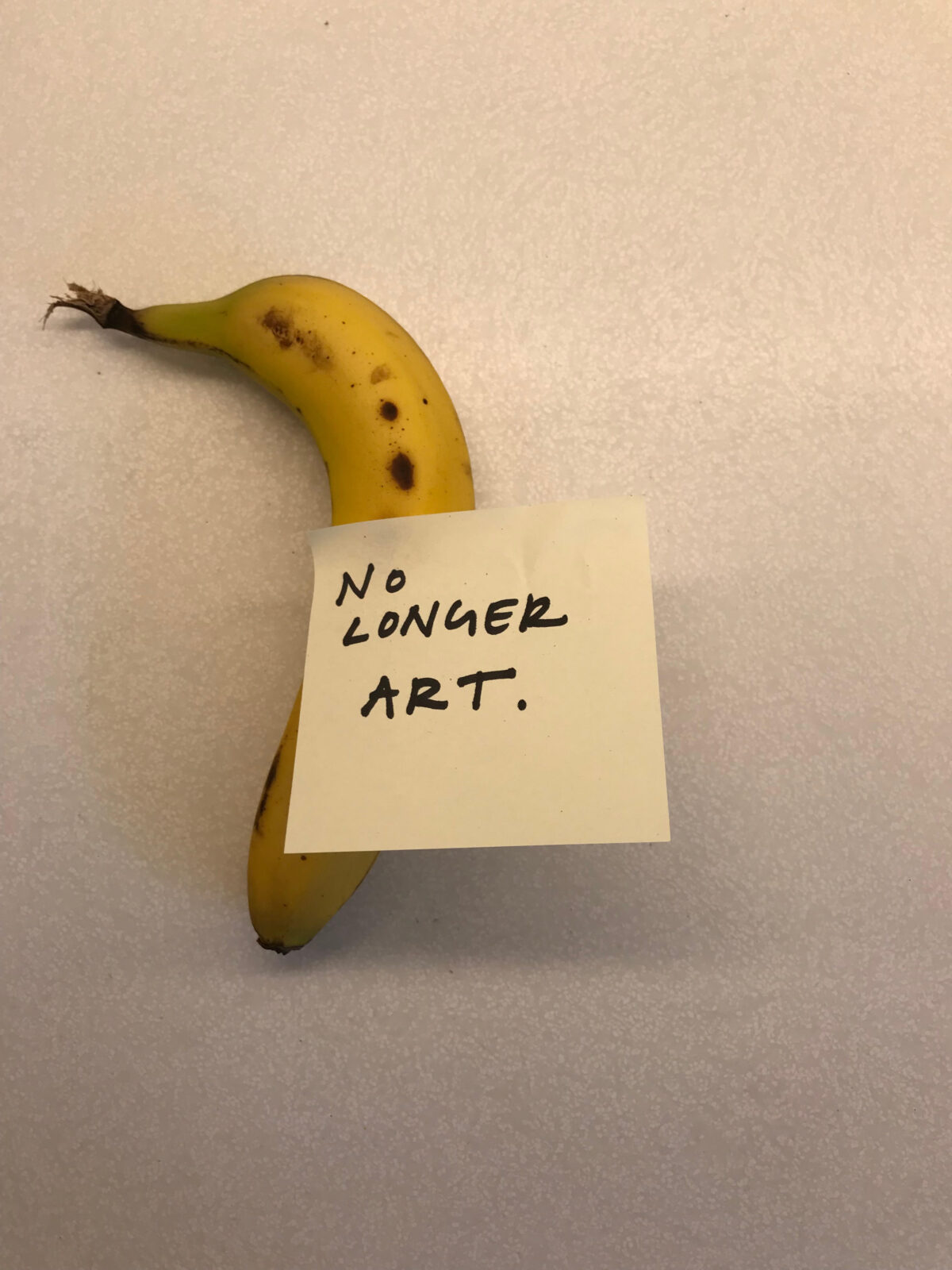

Those perishable items that are still edible—eggs need to be tossed—Nugent brings to the CAM staff office for anyone who cares to take home or eat here. In doing so, she also answers the question of “What is art?” Or at least in part. With the post-it note “No longer art,” Nugent suggests, at least as it relates to Abu Hamdan’s exhibition, that once a banana or a watermelon have ripened, they no longer qualify as art. They have lost their artistic purpose, unlike, say, the tennis shoes, which can remain art indefinitely.

Still, even in exchanging the no-longer-art item with the fresh-art item, is not an exacting replication. For example, each banana is a slightly different shape or color, so Earwitness Theatre changes with each transition. Nugent handles these conundrums deftly. It’s not her first time working with perishable art. “I once worked in a gallery where an artist used plant material, food, and tumeric on a wall,” she recalls. “However, they wanted the food to decompose on its own, so it was not replaced.”

—Alli Beard